In a study of public attitudes towards government paternalism, Clareta Treger finds that, when it comes to their own safety and health, individuals prefer coercive government policies over nudges that steer them towards welfare-enhancing behaviour. Policymakers should consider this when devising strategies to mitigate Covid-19, and future crises

Scholars and policymakers debate whether governments should use more or less coercive tools to promote desired social ends, especially when they intervene in citizens’ private sphere. The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted this debate. The vaccination mandate approved by the Austrian government and the recent decision by the US Supreme Court to block the federal vaccine mandate for large private employers have intensified controversy over governments' authority to take coercive measures to protect their citizens.

How do citizens feel about coercive policies? Given the choice, do they prefer more or less coercion from their government? The answer depends on several factors: the policy domain, who promotes the policy, and what others think. When policies aim to promote personal safety and health, individuals may prefer coercive policy tools over non-coercive alternatives. It also matters whether it’s their co-partisan who sponsors those policies.

My recent study focuses on public attitudes towards government paternalism. This includes policies that aim to protect citizens from inducing self-harm, as opposed to protecting them from harm inflicted by others. These policies are ‘paternalistic’ because they treat adult citizens as if they were children. Such policies abound. Mandatory seatbelts and helmets, tobacco and sugar taxes, mandatory pension savings, and anti-abortion laws are a few common examples.

Coercive policies are often more effective in achieving desired social goals, but can infringe severely on personal freedom

However, policies with a paternalistic hue need not necessarily be coercive. Over the past two decades, the concept of nudges has received much attention from the research community as well as from policymakers. A nudge is a policy intervention that steers people in a desired behavioural direction, while preserving their freedom of choice. Governments across the world established 'nudge units' or 'behavioural insights teams' to incorporate nudges into public policy.

Coercive policies are often more effective in achieving desired social goals, but frequently come at the cost of severe infringement on personal freedom. Thus, the idea of nudging becomes very appealing. Given this trade-off, what makes citizens support paternalistic policies?

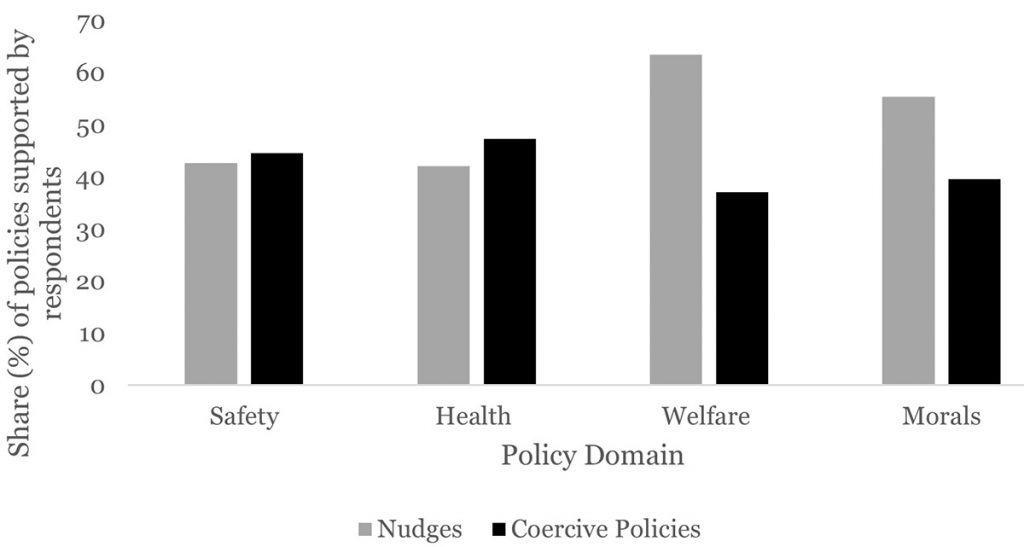

I argue that individuals support coercive policies – and even prefer them over non-coercive alternatives such as nudges – if they promote people's safety or health. My study, conducted among a national US sample, found support for this claim. Americans preferred coercive policies such as taxes and bans to promote healthier nutrition and reduce smoking, over nudges. They were also indifferent to choosing between nudges and coercive policies that concerned personal safety at pools and while riding electric bicycles.

This can be explained by the gravity of the decisions at hand and their possibly detrimental and irreversible consequences. For example, individuals may find it difficult to avoid eating unhealthy products (which are often cheaper and tastier than healthier alternatives) or to quit smoking using will power alone. However, aware of the long-term consequences of such habits, they might welcome significant obstacles to keep pursuing them.

Yet preferences are the opposite way around when it comes to welfare issues and moral convictions. In such cases, individuals strongly opposed coercive policies and preferred the nudges. For example, respondents opposed imposing taxes on people who do not save for retirement or making retirement savings mandatory, preferring instead to nudge people towards saving. People also rejected coercive policies when they dictated behaviours pertaining to moral judgement, such as limiting pornography consumption or limiting the option to undergo euthanasia.

In addition to the policy domain, public opinion and partisanship also shaped support for paternalistic policies. Respondents identifying as Democrats or Republicans had remarkably similar levels of support across most policy domains when someone from their own party appeared to promote the policy. However, this support dropped sharply when a legislator from the rival party sponsored the policy.

Public opinion and partisanship are also key to public support for paternalistic policies

Public opinion was also instrumental in shaping support for the policies. When respondents learned that a majority supported the policy, their support increased. Even a small majority of 55–65% of the public induced this effect. This suggests that people’s perception of what their fellow citizens think matters to their own opinion formation. It may affect their behaviour, too.

These findings highlight several points. First, individuals do not reject coercive paternalistic policies as a matter of principle. On the contrary – they welcome such policies under certain predictable conditions, such as when they benefit their health. Second, attitudes are politicised. Therefore, putting aside their predispositions towards government paternalism and coercion, individuals may be acting in accordance with their party’s cues. Finally, public opinion is itself an actor in shaping opinion.

Individuals do not reject coercive paternalistic policies as a matter of principle; instead, they welcome them under certain predictable conditions

These results are relevant for preparedness for future crises. They are also useful right now, because governments are still experimenting with strategies to mitigate the current pandemic. Governments are seeking the most effective tools to increase vaccine uptake, while beginning to ease mask regulations.

Policymakers should be mindful, therefore, that leaving citizens to make up their own mind (the engage-at-your-own-risk approach), may not necessarily represent public preferences. More importantly, the example policymakers set, and their ability to reach cross-partisan consensus on the most appropriate action, could encourage voters to heed health guidelines and take protective measures.

Finally, the perception of the majority’s opinion on policies that aim to mitigate a crisis is important for attitude formation. Thus, it is paramount to avoid overstating minority positions – provocative and newsworthy as they may be. Rather, efforts should be made to accurately represent the public’s opinion.