The distinctiveness of the new climate change activism, writes Louise Knops, is the unlikely combination of two elements, science and emotion. These challenge deep-rooted beliefs, and introduce a new vision of climate change and its possible resolution

In early 2019, under the influence of Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, the Youth for Climate movement erupted in Belgium, as the Belgian branch of ‘Fridays for Future’. Tens of thousands of young activists marched the streets, every week, to express their indignation at politics and their fear for the future.

This extraordinary mobilisation combined two striking features: a return of modern scientism and explicit emotionality. This is noteworthy in a context where emotions and the rationality of science are often opposed, and where emotional rhetoric is chronically discredited.

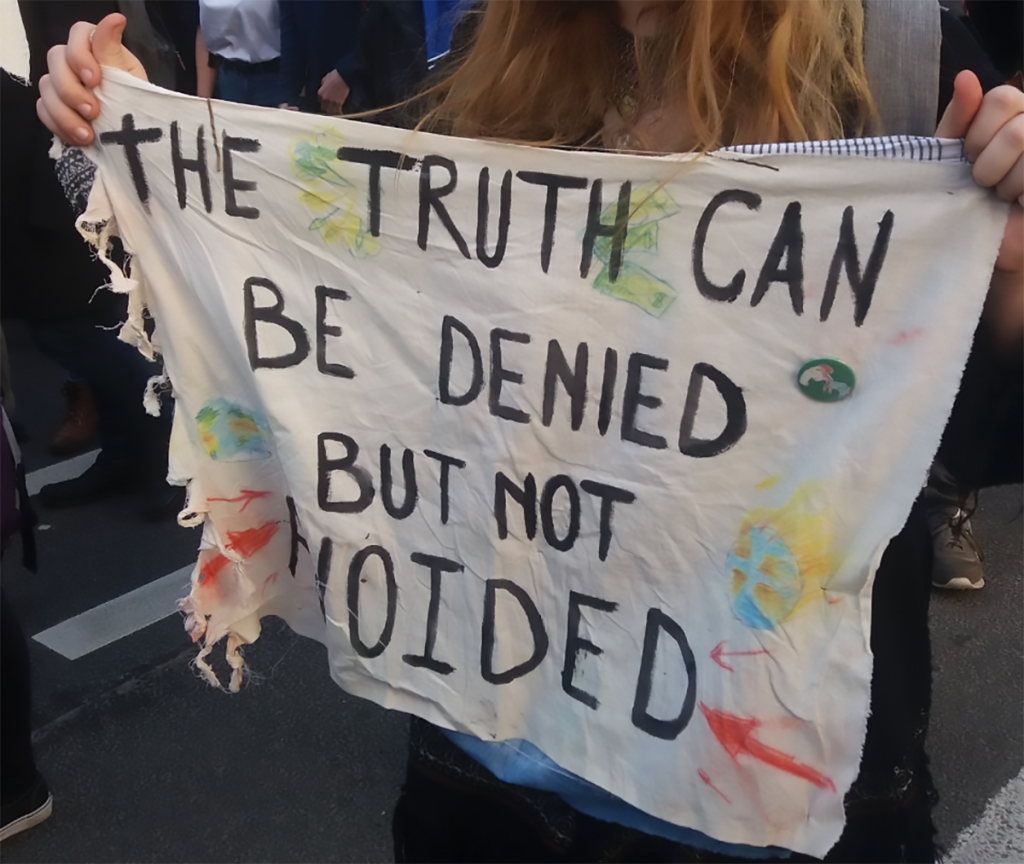

On the one hand, young climate activists are begging politicians to 'please, listen to the science!' This shows the profound epistemic battle in which society is engaged, and the consequences of the current instability of truth.

young activists are showing a way out of the technocratic frame which has dominated climate change politics, and is preventing us from ‘solving’ the ‘climate crisis’

On the other hand, activists are asking everyone to be emotional about it, and this is a good thing. As my recent article in PRX journal discusses, they are showing a way out of the technocratic frame which has dominated climate change politics, and is preventing us from ‘solving’ the climate crisis.

Climate scientists have gathered indisputable evidence of the environmental impact of human behaviour. But they have not (always) given us the tools to get to the heart of the ongoing climate mutation. It is us, humans, and Western humans in particular: the way we relate to one another, the way we envisage our position among other species, the way we move, eat, and construct our sense of identity. And this human fabric cannot be grasped simply through statistics, figures, and graphs. It is also, fundamentally, about emotions and affectivity.

Overlooking the affective dimension of climate change is not only problematic on an abstract, theoretical level. It also directly impairs our ability to develop new ways of relating to the world. For some scholars, the fate of humans itself, as argued by Glenn Albrecht, rests in our ability to navigate 'Earth emotions' (eco-grief, terrafurie, and solastalgia) and to develop new affective sensibilities.

young climate activists have understood, on an intimate level, that the climate crisis is not just another problem to ‘solve’

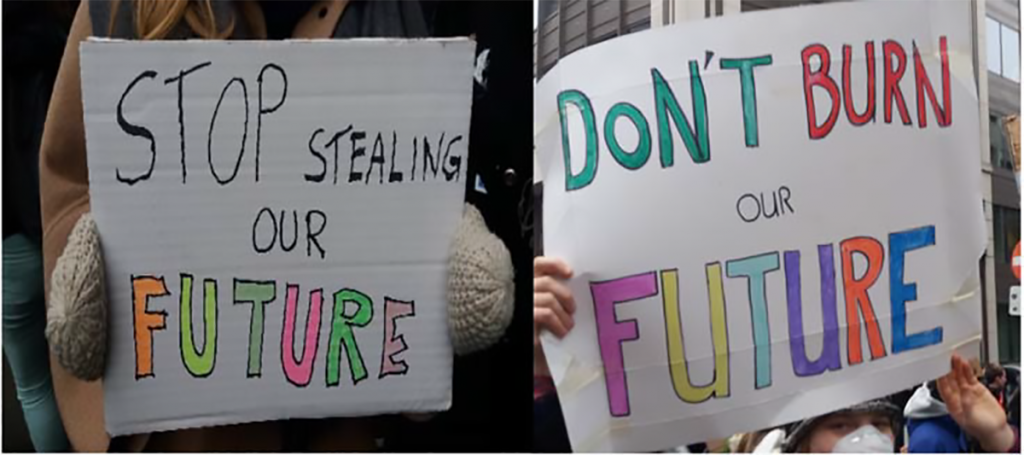

So by exhorting us with protest slogans 'to be angry, and panic'; 'to love and care', 'to wake up, now!', young activists are, in fact, bang on. They have understood, on an intimate level, that the climate crisis is not just another problem to ‘solve’, as Bill Gates and others continuously claim.

Rather, climate change, and our entry into the Anthropocene, are events that challenge deep-rooted meanings and beliefs. They open new 'possible futures and configurations of desire', and, as Marie-Louise Pratt tells us, invite Westerners to 'resituate themselves in the time-space-matter of the Earth'.

When drawing lessons from the recent wave of climate activism, we should thus feel not just a desire to ‘solve’ the crisis. We should feel drawn to reconnect with the natural world. Rather than observing it from afar, we should feel part of it, not on top of it. We should, as Bruno Latour elegantly summarises, come down to Earth and go back to the humus of humans.

Among all the emotions expressed by young climate activists, some are better suited than others to make us ‘feel’ the climate crisis, and ‘land’ on Earth.

Fear, for example, is often conceived as a negative emotion. But it captures the material struggle expressed by young activists: terrified by their attachments to an Earth that most of our behaviour is making uninhabitable. It is fear that allows young activists to navigate the conflicting temporalities of climate change; from the frantic rhythm of modern life to our geo-epoch of mass extinction.

Here, fear brings an intimate dimension to their narratives of collapse: in the projections of their own future lives and deaths, and that of their future children (some activists have renounced parenthood altogether). All situated explicitly against the boundaries of the Earth:

we want to have children, but not on Mars!

Activists' fear for the future, combined with anger, articulates the new generational divide between: 'us, the youth', and 'you, who knew but did nothing, and keep stealing our future!'

In contrast with fear, hope is generally perceived as a positive emotion. But this obfuscates its nature as an ‘inconstant pleasure’, and an emotion which, once disappointed, can turn into hate, as Erika Tucker explains.

Overall, hope is seen positively because it elevates us and drives us forward. But hope can also lock us in the weightlessness of false illusions. Hence, the hopeful indignation of young climate activists, in particular their remaining hope in existing political institutions, may not be conducive to the ‘landing on Earth’ they otherwise advocate.

This is a contradiction activists seem aware of, as testified by their recent support of alternative democratic institutions through, for example, the organisation of citizens' assemblies, as defended by neighbour movement Extinction Rebellion.

Much more powerful than hope is the love climate activists express for the Earth. Love, says philosopher Baruch Spinoza, is 'a union whereby both the lover and what is loved become one and the same thing, or together constitute one whole', whether human or nonhuman. It is this love that articulates activists’ identification with the Earth, portrayed as victim of economic and human abuse (see for example their slogan #SheToo).

In addition, love repositions young activists among other terrestrial species. They are aware of the relations of domination that bind them, and feel the guilt that comes with the harm inflicted on a loved one. It is love which enables activists to cross human-nonhuman boundaries and create a subject that goes beyond their individualities. In their own words, 'We are nature defending itself', and 'We are the climate'.