In June 2021, after twelve consecutive years as Israel's Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu was forced out of office. The coalition replacing him promises change, find Amnon Cavari, Maoz Rosenthal and Ilana Shpaizman. Whether it delivers on its promises is another question

Between April 2019 and March 2020, Israel held three national elections. These resulted either in interim governments or a political-stalemate 'unity' government. Benjamin Netanyahu led all of them.

During these rounds, the vote split between solid support for Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel's longest-serving Prime Minister, and support for Netanyahu's removal from power, primarily because of corruption allegations against him.

The 2021 March elections seemed to result in a political deadlock. However, an unlikely coalition of parties formed Israel's 36th government. For the first time in more than a decade, the Prime Minister is not Benjamin Netanyahu. The new Prime Minister, Naftali Bennett, is a religious Jew — the first in this position to wear a yarmulke.

Bennett leads a party that holds only seven (effectively six) seats of the 120 in the Israeli parliament, the Knesset. Also, for the first time, the coalition includes an independent Arab Party, Ra'am.

This new cabinet is the most diverse in Israel's history. Nine female ministers, two Arab ministers, two openly gay ministers, and a minister with disabilities.

The cabinet of Israel's 36th government is the most diverse in the country's history

Another unique feature of this coalition is that it includes parties from diverse party families. These include nationalist, liberal, social-democratic, conservative, and ethnic parties.

To examine whether the new government represents a change in policy agenda, our Israeli Policy Agenda Project research group analysed founding documents of the new coalition and government — coalition agreements and government guidelines.

In entering the coalition, the party forming the coalition signs an agreement with each of the other parties. These dyad agreements include political arrangements, and policy commitments. Political arrangements consist of ministerial appointments (including those of junior ministers) and allocating leadership positions in parliament. They also relate to procedural decision-making rules that can constrain the government.

As for policy commitments, these are policies the coalition commits to promoting (increased investment in sustainable transportation, for example), reflecting the priorities each partner wants to promote (or block). Party leaders usually negotiate coalition agreements before the government is sworn in, and they are often ratified within the party. These documents are thus much more than a symbolic agenda-setting tool. Most statements in the agreements are either enacted or implemented through cabinet decisions.

We analysed the share of policy attention, the diversity of policies, and attention to specific policies

In addition, all parties must sign up to the government guidelines. As opposed to coalition agreements, which may include controversies between coalition partners, the government guidelines include only issues all partners support. These guidelines are presented to the Knesset when the government is sworn in. Existing work demonstrates that government guidelines serve as a benchmark to assess the initial work of government.

Consistent with the current work of the Comparative Agendas Project, we therefore coded each quasi-sentence in the 36th government's coalition agreements and guidelines. For comparison, we relied on our coding of past coalition documents since 1981. Our analysis examined the share of policy attention (compared to political arrangements), diversity of policies, and attention to specific policies in those documents.

Coalition agreements of the incoming government maintained a relative balance between political arrangements (60%) and policy commitments (40%). This differs significantly from the previous government, which focused mainly on political arrangements (75% of agreements) and is more in line with pre-Netanyahu coalitions.

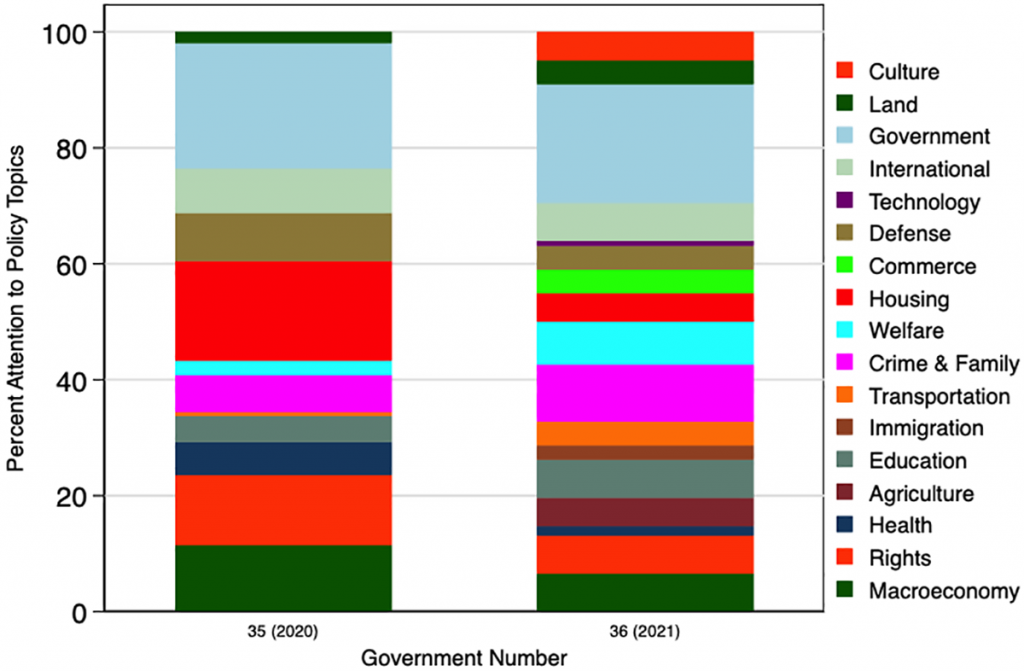

The policy attention is not only more extensive but also more diverse. Of the 21 major policy categories we examined, as the figure shows, the coalition agreements attended to 17. In contrast, the outgoing government attended to only 12. This difference is greater in the government guidelines — 19 topics against only eight topics in the outgoing government.

In particular, the new coalition government has focused attention on issues traditionally sidelined in Israel, such as environment and energy. It has also emphasised issues that had previously received only limited attention, such as welfare and labour.

Among the main conflictual issues in Israeli politics are matters of state and religion. The ultraorthodox parties, who remained outside of government for the first time in 15 years, argue that the new government will change the entire status quo on this issue. We find, however, little support for this concern — less than 10% of the coalition agreements address matters of state and religion.

Our evidence suggests that the new government wants to be a government of change, in both political arrangements and in its policies

These changes are important because once issues are on the agenda, the government is more likely to address them. This suggests that the new government wants to be a government of change, in both political arrangements and in its policies. The real test, however, is whether it can transform its agenda into actual policies, while surviving in power.

We can draw several lessons from this case and the way these agreements were set up. One point is that even when a leader becomes the main personification of a political system, certain political arrangements can unseat them from office. However, forming such an arrangement requires the parties that take on such a difficult challenge to set aside ideological grievances. This means that the parties committed to change a system should focus on the policies on which they can agree, and govern together.