The ‘Global South’ has become a popular meta category in the practice and study of world politics. Exploiting its analytical potential, Sebastian Haug argues, requires explicit engagement with definitions, meanings and the implications of taken-for-granted framings

References to the ‘Global South’ have made it to the centre of debates about world affairs. From climate change activists to diplomats negotiating development finance, ‘North’ and ‘South’ have become staple terminology in media and politics.

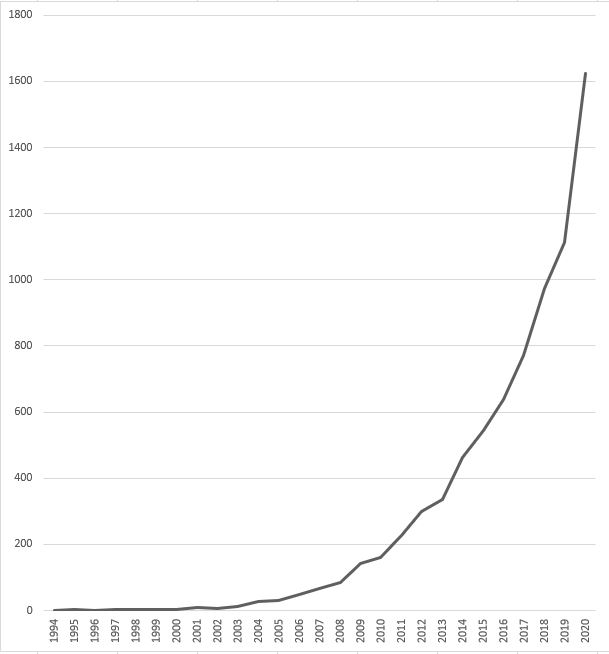

Academic publications also reflect the current prominence of the ‘Global South’. According to the Scopus database, references to the ‘Global South’ in English-language research have expanded exponentially over the last two decades.

A recent Third World Quarterly Special Issue highlights how this steep rise contrasts with significantly lower references to the ‘Global North’. In order to shed light on the popularity of the 'Global South', we suggest approaching it as a 'meta category': a tool that helps map global space by classifying a wide range of phenomena.

As a meta category, the ‘Global South’ has taken on a variety of meanings. It refers not just to landmasses and waters south of the equator, the strictly defined hemispheric south. Instead, the term has been a general rubric for decolonised nations roughly south of the old colonial centres of power.

The first references to the ‘South’ at the United Nations can be traced back to the 1960s. After the Cold War, the qualifier ‘global’ began to be added. This underlined interconnectedness in a global(ised) context. It also highlighted the expanding economic and political clout of players across Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Three understandings of the ‘Global South’ have been particularly prevalent in the analysis of world politics. First, people generally take the ‘Global South’ to refer to poor and/or socio-economically marginalised parts of the world. The World Bank income-per-capita index has been a popular proxy for mapping aggregate development levels, and for comparing countries and regions over time.

‘Global South’ refers not just to the hemispheric south. It has been a general rubric for decolonised nations located roughly south of the old colonial centres of power

Second, the ‘Global South’ has stood for cross-regional and multilateral alliances with references to the 1955 Bandung Conference, the Non-Aligned Movement and the Group of 77 at the United Nations. This is a tricontinental space with platforms and cooperation practices beyond those dominated by former colonial powers.

Third, the ‘Global South’ has been presented as a space of resistance against neoliberal capitalism. Moving beyond country-based perspectives, this has reframed the ‘Global South’ as a marker for anti-hegemonic engagement that can happen anywhere.

A wide range of research on world politics can benefit from drawing on the ‘Global South’ as a meta category. This entails defining what we mean by it. It requires us to steer clear of sweeping generalisations, such as assuming that ‘Southern’ countries or people are per se destitute. It also means we should avoid superficial frames, such as referring to all studies somehow related to Africa, Asia or Latin America as ‘Global South’ research.

Instead, research and writing should try to reflect on why we use North-South terminology to approach research questions. It should also consider what the implications of this choice are.

We should avoid superficial frames, such as referring to all studies somehow related to Africa, Asia or Latin America as ‘Global South’ research

Contributions focusing on the ‘Global South’ with analytical success make explicit why this focus matters, and how it relates to the analysis of global or transnational linkages. The economic and political 'rise' of China, India and Brazil, for instance, has affected their promotion of solidarity among 'Southern' countries in international governance fora. Discussions about transnational inequalities – from climate justice to comparative value of passports – can also benefit from carefully applied North-South framings.

As a relational category, the ‘Global South’ can help to analyse structural dynamics in today’s world that have concrete implications. It directs attention to links between sites and across time, such as historically grown patterns of inequality. In so doing, it highlights the need to consider (post)colonial and (post)imperial trajectories when interpreting the current contours of world politics.

As a relational category, the ‘Global South’ directs attention to links between sites and across time

Analysing the use of the term ‘Global South’ itself can, in turn, reveal more about the production and dissemination of knowledge. With Paolo Freire’s participatory action research, for instance, we can examine how categories come to be employed, and by whom. Edward Soja’s spatial theory, in turn, points to different dimensions of how categories are filled with meaning across sites. Inspired by the writer Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie, a focus on polyphonies – the ways in which different practices contribute to a joint phenomenon – allows us to discuss the complexity of categories used by many people, in many different ways.

An explicit and differentiated engagement with meta categories like the ‘Global South’ matters because it allows us to reflect on, and improve, the tools we use for making sense of global space. As such, research on meta categories raises – and can contribute to tackling – fundamental questions in the study of world politics.

Sebastian is co-editor of the Third World Quarterly Special Issue The ‘Global South’ in the study of world politics