By stitching together new alliances, we can assemble united yet internally diverse collective identities, leading the way toward democratic transformations. Lucas N. Veloso explores the transformative carnival protests of the Brazilian mental health movement

Since 2015, I’ve worked as an activist and ethnographer in Brazil’s mental health movement, which challenges incarceration and stigmatisation of those with mental health issues. My research delves into the obstacles citizens experiencing mental disorders encounter to exercising their right to assembly. In 2019, the carnival protest staged by the mental health movement opened up inspiring opportunities for democratic transformations. Each opportunity stems from 'political stitching' – a concept inspired by the Hendriks, Ercan, and Boswell political theory – and it calls for 'mending democracies'.

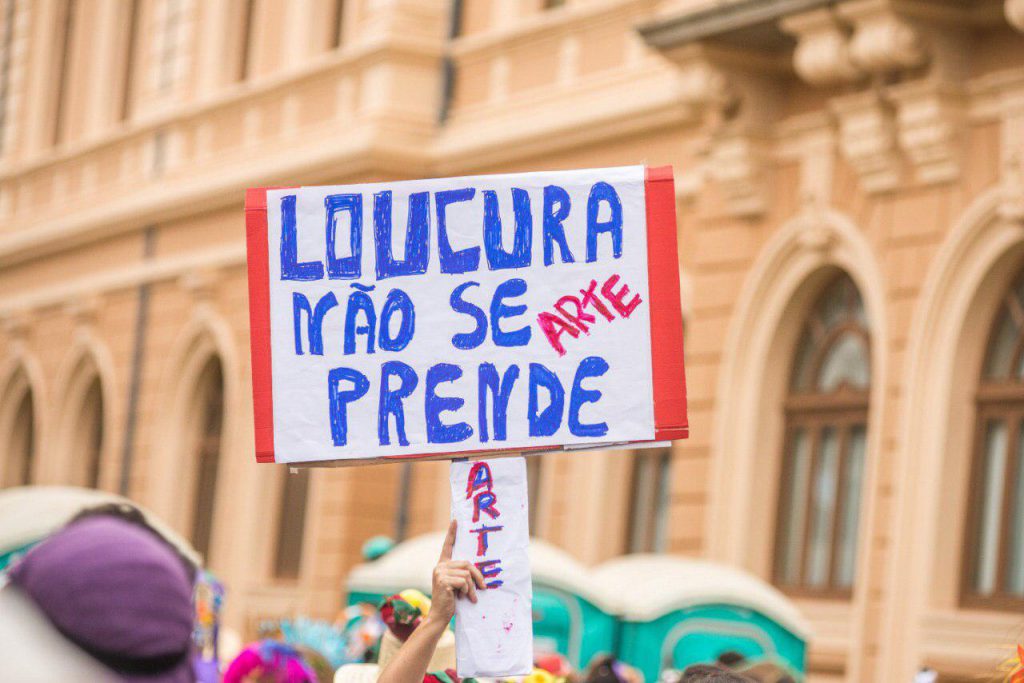

Political stitching describes the inventive political action of creatively producing shared identities by joining different multiple selves in a collective struggle for political change. When mental health activists sew costumes for their carnival protest, they do more than just thread together different fabrics. They stitch alliances of different identities. They join multiple movements and groups – Black, Indigenous, feminist, queer, landless, and homeless activists – to build a temporary assemblage. This results in an improvised yet carefully articulated political identity in response to urgent contextual challenges.

While the collective articulates a common identity, it does not erase internal difference. Like a colourful carnival costume, it is both one, and many. Political stitching highlights the precarity and temporality of identities. These identities are assembled through practical work on the ground, yet are easily undone. Stitching can be fun, but it also entails injury and pain. Political stitching encourages us to explore creative and solidaristic ways to repair and enhance our democratic fabric.

Since its origin in the mid-1970s, Brazil's mental health movement has employed creative protest techniques as a critical instrument for change. Once a year, in May, this collective of healthcare professionals and persons facing mental health issues holds a day of protest. Its collective action has played a major role in closing oppressive mental asylums and recognising the rights of persons in mental distress.

Another crucial aim of the movement's annual protest is to fight enduring social stigmas associated with mental disorders. In public discourse, people suffering from mental health challenges are often characterised as dangerous, incompetent, and at fault for their own suffering. This leads to widespread discrimination, exclusion, and inequality.

In 2019, the rise of the right-wing government in Brazil brought renewed challenges. Bolsonaro's government cut vital public health services. Under his administration, oppressive practices like electroshock therapy began to be more widely used, and religious 'therapeutic' asylums began growing in number.

Considering the highly difficult political context of 2019, members of the mental health movement decided that their claim to public space needed strengthening. Making their protest more inclusive and diverse was one way of achieving this goal. The movement decided to invite and represent other social groups oppressed by the right-wing government to fight alongside them: women, Black, Indigenous, and queer individuals, the landless, and the homeless.

Solidarity and social bonds across different identities are crucial for collective empowerments and transformations, as Zohreh Khoban argues in her exploration of the Iranian protests in this series. However, social movement theorists posit that establishing collective identities is a difficult task. Collective identities navigate between unity and singularity, between joint and individual political expression. This necessitates shared frameworks to forge a sense of 'we' while recognising individual identities.

In response to this challenge, the movement staged its 2019 street protest as a Brazilian carnival parade. Its improvised structure allowed each social group to be part of a united movement and, at the same time, to be differentiated by their specific flags, costumes, and performances. The collective identity emerged through political stitching, assembling diverse selves into a unity, while preserving their differences.

Hans Asenbaum’s Politics of Becoming helps us to understand how the stitching of carnival costumes, performances and identities can counter mental disorder stigmas. When people present themselves in an unexpected manner, they reject the labels usually assigned to them. This identity interruption can act like a 'gap' or 'surface' for the presentation of new 'temporary faces' and democratic innovations (p.9). Taina Meriluoto's article for this blog series has also powerfully demonstrated this.

The performance of the Queen, Prince and Princess of the carnival parade enacts an embodied claim to be recognised by names and values other than those generally attributed to them. The performance challenges the devaluation of Black lives in Brazilian society and, in doing so, turns societal hierarchies upside down.

The block of people affected by environmental disasters embodies a creative demand for empathy, solidarity, and public support. Tears cover protesters’ faces. Aprons are smeared with brown paint to symbolise the aftermath of a collapsed dam.

The anonymising masks highlight that disasters can impact on anyone. Cards carry mourning messages.

Source Ethnographic records

In the mental health block, eyes on the costumes boldly confront the stigma of madness. They encourage the public to look closely and question whether individuals with mental disorders truly pose a societal threat. They invite onlookers to consider the extent of their suffering from societal stigmatisation.

Brazil's mental health movement shows us how we can democratically stitch hybrid political identities, in everyday life or during a protest, that catalyse democratic transformations. When we dare to challenge oppressive identities assigned by society in solidarity with others, in creative and democratic ways, conditions of visibility change. In seeing ourselves and others differently, we move towards democratic futures, one stitch at a time.