Almost every country in the world has a legislature. They are at the centre of democratic politics, but also take on crucial roles in authoritarian regimes. Felix Wiebrecht illustrates how a multidimensional approach helps us to understand their role in dictatorships and paves the way for more research

Hager Ali notes that we need better typologies of authoritarian regimes. The same applies to their legislatures. They can differ from each other as much as from their democratic counterparts, despite earlier research describing them as nothing but ‘window-dressing’ or rubberstamp institutions.

But even under authoritarianism, legislatures matter. This is increasingly accepted in comparative politics, but research still struggles to identify why exactly that is the case. In authoritarian regimes, legislatures have, for instance, been credited with important roles in co-optation, power-sharing, and the collection of information. However, as scholars of authoritarianism, we seem to emphasise one task over another without linking these features into a unified framework of authoritarian legislatures.

Recent research has taken a step toward advancing our understanding of authoritarian legislatures by comparing their strengths across regimes. While some authoritarian legislatures are correctly described as mere democratic façade, others have a much more significant impact on authoritarian politics.

Yet legislative strength is often primarily used to refer to parliaments’ relationship with the executive, i.e., the dictators. While this may be the most important dimension, it is only one of several. Therefore, a more disaggregated approach may prove useful in understanding their role and consequences in authoritarian regimes.

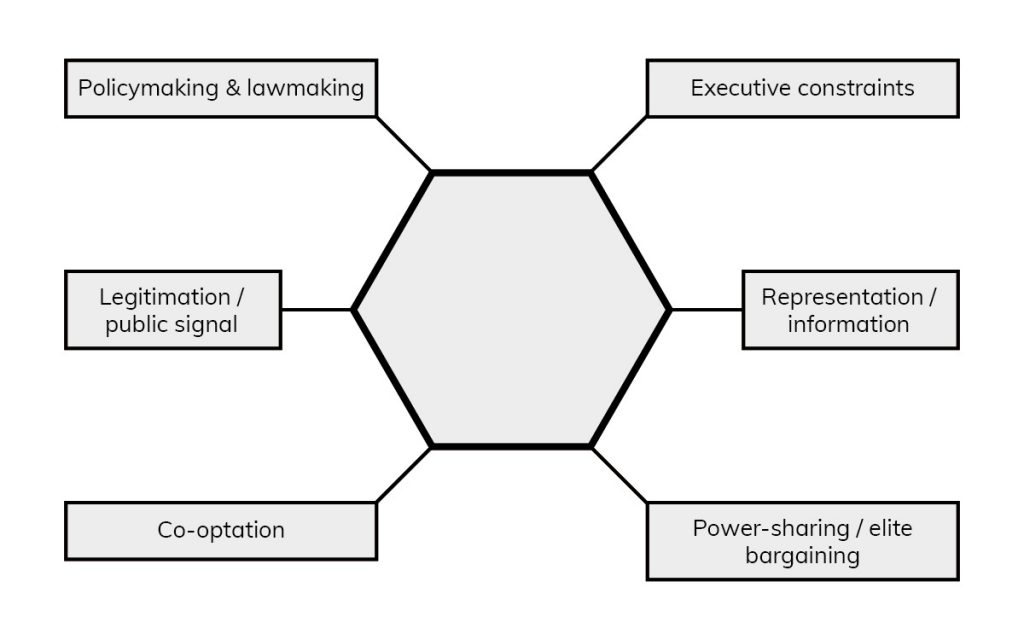

Like any legislature, authoritarian legislatures fulfil several functions simultaneously, including co-opting outsiders, legitimation, and providing a forum for elite bargaining

In fact, legislatures always perform multiple tasks at once. While the name suggests that law-making is legislatures’ primary task, even in democracies, they fulfil several functions simultaneously. These may also include linkage, representation, authorisation, and legitimation.

The same applies to authoritarian legislatures. They co-opt regime outsiders, legitimate the regime, and provide a forum for elite bargaining, all at the same time. Figure 1 shows how we can conceptualise legislatures’ tasks under authoritarianism.

The question then is not whether a legislature in any given regime performs these functions. Most legislatures in authoritarian regimes will perform all six tasks at least to some degree. For instance, even the Cortes in Spain under Franco engaged in lawmaking. The Vietnamese National Assembly, although primarily focused on portraying regime unity, also co-opts a small number of non-Party members. Instead, the question is to what degree authoritarian legislatures engage in these activities.

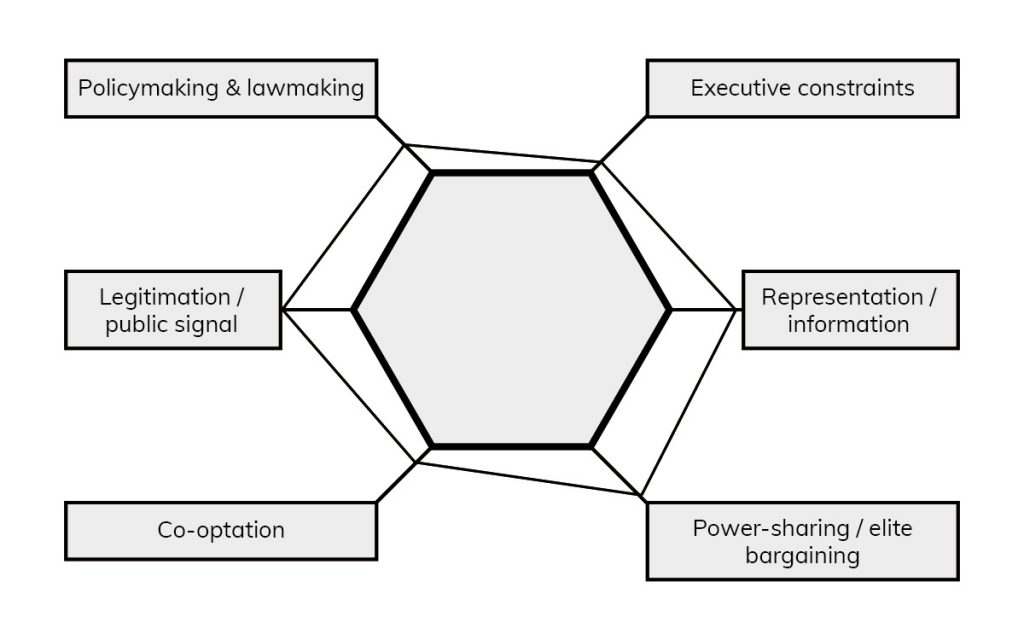

While China's National People's Congress has little ability to constrain party and government leaders, it fulfils several other functions, which can each be compared with other legislatures

Consider the example of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC). The NPC hardly constrains party and government leaders. However, we have evidence that behind the scenes, bargaining between elites and different government agencies is relatively common. Yet, as in Vietnam, it allows the maintenance of an appearance of strength and elite unity toward the public.

Since the NPC only accommodates a limited number of delegates that are not members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), its potential for co-optation is limited. On the other hand, its delegates have been shown to transmit important information upward.

Based on this previous research from the context of China, I invite scholars and practitioners to think of the NPC according to Figure 2. It shows that the NPC can fulfill different functions simultaneously but to varying degrees. Legislatures in communist regimes, for instance, send a stronger signal of elite unity to citizens. Meanwhile, in competitive regimes, they may actually be used as a scapegoat to improve the public perception of dictators.

The NPC’s impact on policymaking may, in comparison to other legislatures, still be limited. Nevertheless, it should be stronger than legislatures’ influence in places such as the Middle East.

Since research on China’s NPC is relatively advanced, it is possible to produce the hexagon on the basis of existing studies. Other regimes, however, lack comprehensive studies on legislatures which makes it difficult to conceptualise them in the same way.

To generate a more nuanced typology of authoritarian legislatures, we need more research on their effects and inner workings in different regimes. Recent studies have paved the way for emerging research agendas, for instance on understanding legislators’ backgrounds, the work of committees in developing countries, and legislative amendments. Advancing along these lines will help us to move beyond current debates on authoritarian parliaments.

As almost every country has a legislature, it makes little sense to debate if they matter or not. Instead, we should ask ourselves more specifically where, when, for what, and for whom legislatures in authoritarian regimes matter.

We must move beyond asking whether a legislature exists to ask where, when, for what, and for whom legislatures in authoritarian regimes matter

Empirically, this also entails moving beyond treating the mere existence of a legislature as an indicator of anything. A legislature may or may not be constraining the executive. It may or may not be active in lawmaking. And so forth.

Future research should therefore also strive for more comprehensive data collection efforts concerning legislatures in authoritarian regimes. Geddes, Wright, and Frantz, for instance, only include a question on whether the legislature houses an opposition in their dataset. This can give us an idea about parliaments’ potential for co-optation but is not enough when studying legislatures.

While it may be challenging to collect more comparative data across parliaments, such efforts will be extremely rewarding. Understanding the extent to which they perform all functions mentioned above goes beyond the mere study of legislatures. It will also shed light more generally on issues of elite politics, redistribution as well as political economy, and regime stability in authoritarian regimes.