Michal Malý and Asker Bryld Staunæs argue that synthetic dissidents mark a new form of opposition politics. In authoritarian regimes, AI avatars and chatbots can propagate risky speech without exposing a single, identifiable speaker. This can protect journalists and activists, but it also changes how responsibility, authenticity and repression work

Artificial intelligence (AI) has moved to the foreground of political communication. It no longer works only behind the scenes as data analysis, campaign infrastructure, or automation. Increasingly, AI appears as a political persona — with a name, a face, and a public voice. This shift marks the rise of what we call synthetic politics.

By synthetic politics, we mean political practices in which AI systems are not merely tools but act as identifiable political agents. They speak in public, respond to citizens, articulate political positions, and sometimes even claim political representation. Recent examples include AI Steve, a synthetic candidate in the 2024 British general election, Albania’s AI minister Diella, and the Danish Synthetic Party.

In democratic societies, this development has sparked debates about trust, legitimacy, and accountability. Critics ask whether AI actors can be held responsible or whether voters can meaningfully consent to non-human representation. These are important questions. But they rest on one key assumption: that people can speak publicly without fearing arrest, harassment, or professional ruin.

In authoritarian regimes, that assumption collapses. Here, synthetic politics is not mainly about trust. It is about survival.

Authoritarian power does not depend on winning arguments. It depends on identifying speakers. One punished individual often deters hundreds of others. That is why repression focuses on names, faces, and networks.

Watchlists, facial recognition, hacked phones, border interrogations, pressured employers, and 'informal' visits from security services all serve the same purpose: to attach speech to a body that can be disciplined. Visibility becomes vulnerability. Silence becomes rational.

Authoritarian power depends on identifying speakers. Repression focuses on names, faces, and networks

This is the context in which synthetic dissidents emerge. They use AI-generated faces, voices, or chatbots to push dissenting speech into public view while shielding the people behind it. The goal is not anonymity for its own sake. It is to lower the price of speaking.

A synthetic dissident is not a fake person meant to deceive. It is a protective interface. The message stays public. The human sender becomes harder to identify and punish.

After Venezuela’s disputed 2024 presidential election, repression intensified sharply. Independent media outlets faced censorship, blocked websites, and arrests. Appearing on camera became dangerous. Being recognisable became a liability.

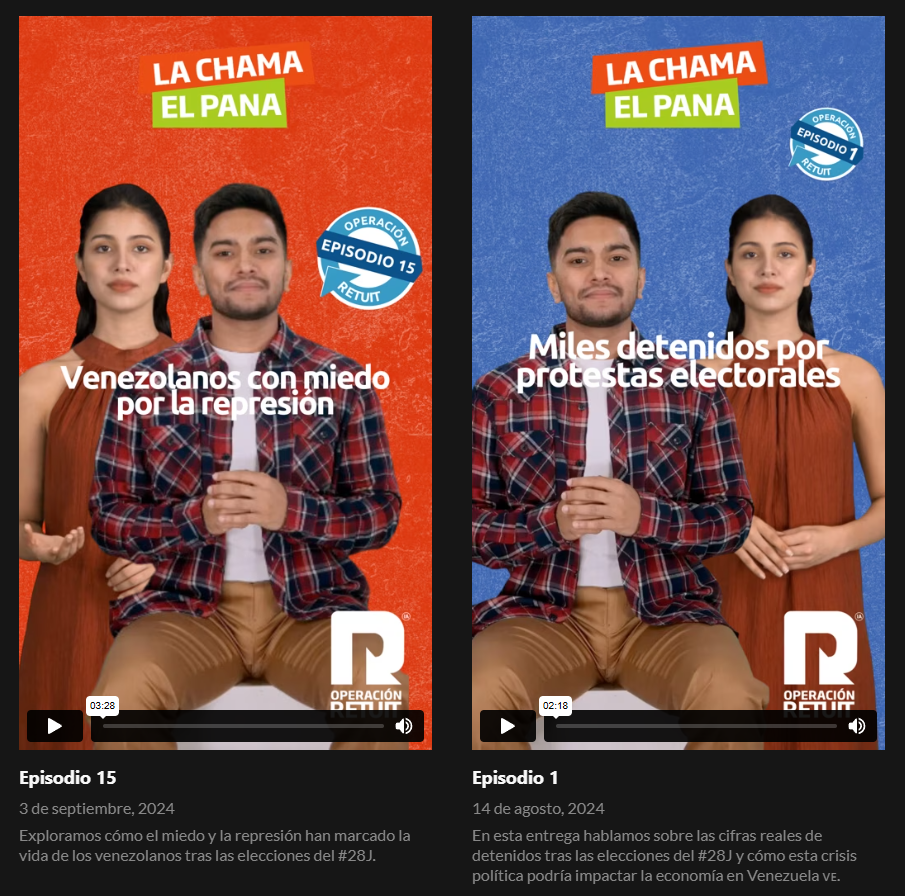

In response, journalists launched Operación Retuit. Instead of identifiable reporters, AI-generated avatars such as La Chama and El Pana began presenting verified news reports. The reporting itself did not change. Journalists still gathered sources, checked facts, and documented abuses. What changed was the messenger.

Screenshot from Connectas.org

The avatars read the news so that real reporters did not have to show their faces. This simple shift mattered. It allowed information about protests, detentions, and repression to circulate while denying the state a clear target. The avatar functioned as a buffer between speech and punishment.

For audiences, the format was unfamiliar at first. But in a climate of fear, unfamiliarity can be preferable to silence. Synthetic presenters kept journalism visible when traditional visibility had become too risky.

Belarus offers a different example. Ahead of tightly controlled elections, opposition actors introduced Yas Gaspadar, an AI chatbot presented as a 'candidate'. This was not a serious attempt to win office. It was a political statement.

The chatbot answered questions, articulated grievances, and remained publicly present in a system where real opposition candidates face imprisonment or exile. As opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya put it on X: Frankly, he’s more real than any candidate the regime has to offer. And the best part? He cannot be arrested!

That line captures the logic perfectly. In a hollow electoral system, a synthetic candidate exposes the emptiness of political competition. The chatbot does not fear detention. It does not disappear. Its presence highlights what repression removes from politics.

Here, synthetic dissent does not protect journalism but reveals authoritarian theatre. Yet the mechanism is the same as in Venezuela: separating speech from a punishable body.

Synthetic dissidents work because repression follows patterns. States target identifiable people. Synthetic personas interrupt that chain. They do not eliminate surveillance, but they make attribution slower and less reliable.

Still, this tactic has limits. Synthetic dissidents keep information visible, but they do not automatically build trust, organisation, or durable opposition movements. They protect speech more than they create coordination. In some cases, they may even turn dissent into content rather than mobilisation.

Synthetic personas may not eliminate surveillance by authoritarian states, but they do make attribution slower and less reliable

There is also a clear risk of imitation. Regimes can deploy their own 'opposition' avatars, flood platforms with fake resistance, or claim that all dissent is artificial. What protects activists can also be weaponised.

This creates a dilemma for policy debates. Blanket bans on synthetic political content may reduce some forms of manipulation. They may also remove a crucial safety layer for journalists and activists operating under threat.

Synthetic dissidents exist because, in many political systems, speaking as yourself costs too much. The key question in authoritarian settings is not whether synthetic media enhances democratic legitimacy. It is simpler and harsher: can someone be punished for saying this?

Where the answer is yes, AI avatars and chatbots are not gimmicks. They are tools of political survival. As repression tightens, dissent adapts. Synthetic dissidents show how technology can be used not to replace politics, but to keep it alive when visibility itself has become a weapon.