Accurate data are needed to track human rights performance worldwide. But the range of different data sources available can be confusing, especially to non-experts. Anne-Marie Brook and Kobe Amos explain what qualities set Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) data apart

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) aims to fill existing gaps in human rights measurement. The goal is to cover every right in the core United Nations human rights treaties and beyond.

However, different sets of rights require different methodologies to be accurately measured. For this reason, HRMI uses one methodology for civil and political rights and another for economic and social rights.

Violations of civil and political rights often happen in secret, and public disclosure of violations is patchy and unreliable. To fully grasp a state’s civil and political rights performance, HRMI goes directly to human rights practitioners on the ground to find out what’s really going on. To collect our data, we use a secure, online, multilingual survey.

Most governments tell their people they are doing the best they can with what they have. HRMI methodology finds out whether that’s true

When it comes to economic and social rights, most governments will tell their people they are doing the best they can with what they have. HRMI adopts the SERF Index methodology to find out whether that’s true. Our country scores compare how well governments are doing compared to other countries with the same level of income. We can then reveal whether a government is, in fact, doing all it can and meeting its obligations under Article 2 of the International Covenant on Economic Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). This obliges states to progressively realise these rights 'to the maximum of its available resources'.

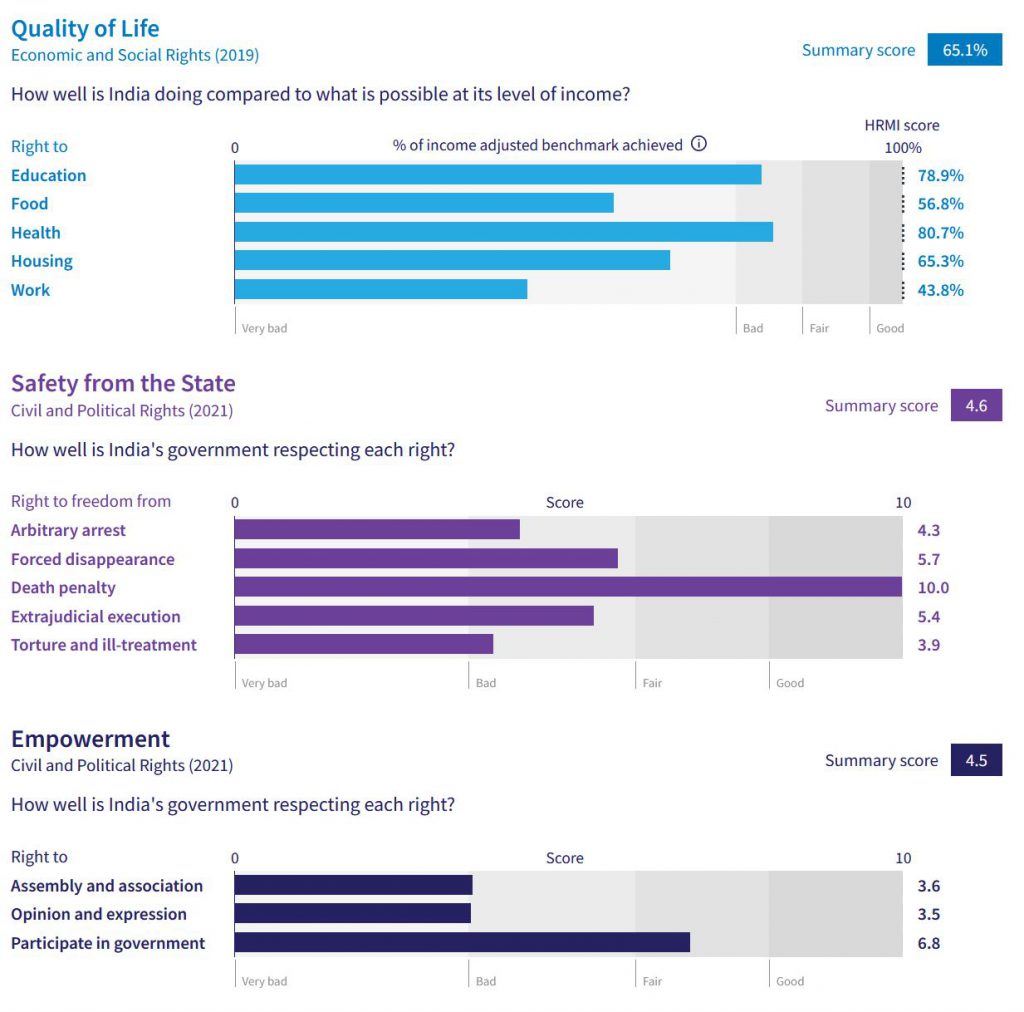

HRMI currently produces metrics for eight civil and political rights and five economic and social rights defined in international law. The Rights Tracker provides an easy-to-read and accessible visual presentation of each country's scores, which can be especially useful to non-experts. The following image shows a summary of scores for India.

The human rights data landscape is unique and varied. This means that some data users may benefit more from certain initiatives than others. Several key features distinguish HRMI data and methodology:

HRMI uses rights as defined in international law. Other initiatives, such as Freedom House, CIVICUS, and V-Dem, have variables covering some human rights aspects. However, human rights is not their focus, because they specialise in assessing related concepts such as civic space or democracy. HRMI’s human rights orientation makes it directly useful to hold states accountable when they fail to meet their international human rights obligations.

Most initiatives rely either on qualitative expert surveys of academics (e.g. V-Dem), or on the coding of documents such as US State Department Country Reports or Amnesty International Annual Reports (e.g. CIRI and Political Terror Scale (PTS)). HRMI uses an expert survey to seek answers from human rights defenders, journalists, lawyers, and those actively monitoring human rights. Their knowledge is essential to produce robust data grounded in grassroots knowledge, which is credible to civil society.

The HRMI expert survey also gathers qualitative answers containing extra information on the human rights violations reported. Our 'people at risk' data highlight which groups of people the experts identify as vulnerable or at risk, and adds important context to the country scores. At-risk groups include women, protestors, LGBTQIA+ people, and so on.

While measurement projects often overlook economic and social rights, HRMI is much more comprehensive. Currently, it creates scores for five economic and social rights (the rights to education, food, health, housing, and work), as well as eight civil and political rights. Other data projects focus solely on one right (e.g., Press Freedom Index) or have variables only for civil and political rights, such as the Major Episodes of Political Violence (MEPV) and PTS.

HRMI methodologies are not only peer reviewed and accepted by academics; they are also co-designed with on-the-ground human rights experts. We are now building on this to develop a new dataset more relevant to the investor community.

Our human rights expert survey is now available in thirteen languages, allowing local human rights practitioners to share their first-hand, accurate knowledge with the rest of the world. This approach ensures that our expert survey is a tool that gives voice to human rights experts in countries worldwide to share their knowledge globally in the form of quantitative metrics of civil and political rights.

Our expert survey allows voices not traditionally heard in human rights initiatives to become meaningfully included

This is especially valuable for human rights experts from outside Western and high-income countries. It means that voices not traditionally heard in human rights and related measurement initiatives become meaningfully included and amplified.

HRMI economic and social rights data also provide a solution to the serious problem of ‘ingrained income bias’ that the World Bank has identified with currently available Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) scores used by the investment community. At present, social (‘S’ pillar) data correlates with GDP per capita. This means that lower-income countries are missing out on ESG investment, even if they have good governance and are doing comparatively well with few resources. HRMI’s income adjustment methodology elegantly solves this problem.

Quantitative measures of human rights are certainly not new. However, human rights advocates and government policymakers often do not use them. HRMI’s explicit objective is to change this by producing robust data that are useful.

Collaborative initiatives like HRMI produce robust data that help hold governments accountable for their human rights record

As the blog that kickstarted this series argued, good data is essential to understand and fulfil human rights. In this sense, independent, global, and collaborative initiatives like HRMI can help hold governments accountable for their human rights record.

Our data exist to be useful, and we are happy to see them used increasingly by journalists, scholars, governments, the private sector, and civil society worldwide. Because what gets measured, gets improved.