Dragomir Stoyanov analyses the outcome of recent Bulgarian elections, which, just like the April elections a few months ago, have failed to resolve the power struggle between parties of the establishment and new protest parties. The prospect now looms for combined presidential and parliamentary elections in autumn

It is a hot summer in Bulgaria – but there's more than just a heatwave making Bulgarians’ lives uncomfortable. Political temperatures are high too, with a snap election held on 11 July. After three failed attempts to form a government, parliament was dissolved, and new parliamentary elections scheduled. The July election follows the regular election on 4 April, in which governing party Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) won a slim victory. The election was also notable for the emergence of new parties of protest in parliament.

The July election broke several political records, one of which was a record low turnout, of 42%. This was a rude awakening not only for the opinion polling agencies (which had predicted significantly higher turnout) but for some politicians, too.

According to political observers, there were two reasons. First, it was the holiday season. In July, many Bulgarians prefer to go to the beach than participate in political life. Second, the government implemented machine voting for the first time. All polling areas with more than 300 registered voters had to use the new machines. As a result some people – generally older people and those with lower education levels – abstained. This demographic was unsure whether they would be able to handle voting through a machine.

The establishment parties, and especially the party of government over the past decade, GERB, came under attack during the campaign. The caretaker government led by Stefan Yanev, a military officer appointed by the Bulgarian president, began an overhaul of GERB personnel. The overhaul exposed multiple corruption cases and mismanagement by the GERB administration.

Media coverage, which had previously been favourable to GERB, became much more critical. So it was not surprising that, without its usual control of the government and media, GERB lost its first parliamentary election since it was founded in 2006.

without its usual control of the government and media, Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) lost its first parliamentary election since 2006

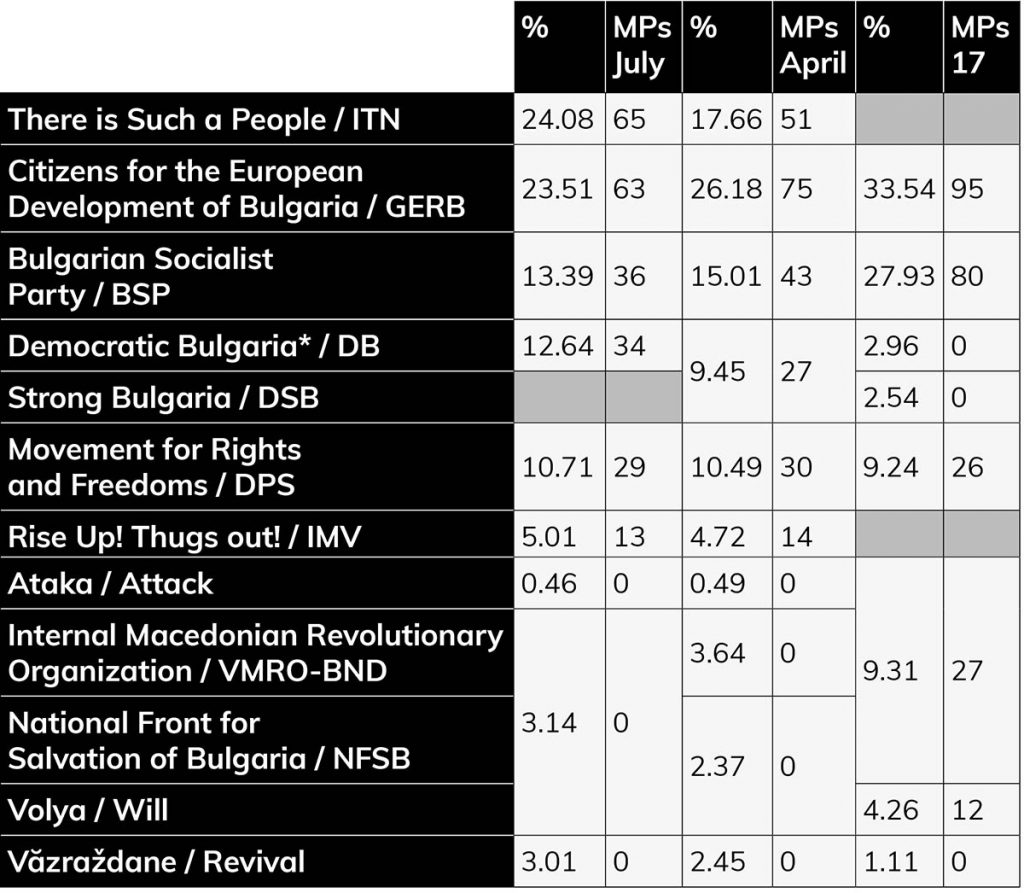

The other establishment party, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), continued its decline. BSP's share of the vote shrank even further compared to the April elections, giving the party its worst result since 1989. The party seems unable to resolve issues to do with its ideological positioning. It is also failing to attract young and educated people. BSP continues to be the party of older people with lower educational levels.

The third of the old parties, the DPS (the party of Bulgaria's Turkish minority), held on to its share of the April vote. Since 1989, the party has been, and remains, an important potential coalition partner because it represents a significant number of voters.

The three protest parties – There is Such a People (ITN), Democratic Bulgaria (a coalition of three parties) and Rise up! Thugs out! – were active participants in the street protests of 2020.

In the April elections, the parties surprised many observers by securing significant representation in Parliament. In the July election, they re-entered the National Assembly, two of them improving considerably on their April results.

The social conservative populist party ITN is led by popular showman Slavi Trifonov. ITN increased its vote by more than 6% after a campaign under the slogan 'It’s time for something else.'

the three protest parties surprised many observers by securing significant parliamentary representation in the April elections

Democratic Bulgaria, a right wing-liberal coalition of three small parties – Democrats for Strong Bulgaria (DSB), Yes, Bulgaria! (DB), and the Greens – increased its share of the vote, too. Its support appears to come mostly from young, urban and well-educated voters.

The social-liberal coalition Rise Up! Thugs Out! slightly improved its April result, receiving 5.01% of the votes.

Despite their successes, the protest parties did not gain the 121 MPs (out of 240) required to form a majority government. The parties of the status quo, therefore, still prevail.

The far-right parties had not succeeded, as single parties, in securing representation in Parliament. Prior to the July election, they formed a coalition (Bulgarian Patriots) of three parties – Internal Macedonian National Organization-Bulgarian National Movement (VMRO-BND), National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (NFSB), and Will (Volya). Again, however, they did not secure enough votes to gain any seats in Parliament.

The far-right parties' campaign concentrated on the Turkish minority and its electoral influence. It also targeted the Bulgarian Roma minority, the LGBT parade in June, and the conflict with Macedonia over Macedonian intentions to start EU accession negotiations.

The other two far-right parties, Ataka (Attack) and Văzraždane (Revival), received 0.46% and 3.01% respectively. Văzraždane is a relatively new actor on the far-right political spectrum, with very similar rhetoric to Ataka. Without Ataka's discredited and eccentric leader Volen Siderov, Văzraždane seems to be the far-right party with a political future.

A presidential election is planned for the autumn. The incumbent president, Rumen Radev, is projected to win, but the dynamic nature of Bulgarian politics could bring something new. There is currently speculation that Slavi Trifonov could stand. This follows his June statement that he would not become a Member of Parliament but seek political responsibilities elsewhere.

At the same time, new parliamentary elections are not off the cards. On the day after the July election and before the official results were announced, Slavi Trifonov surprised everybody by proposing a minority government composed of young and ambitious people. A few days later, he withdrew his proposal.

So ITN’s first post-election moves have been confusing, and signal continued political instability ahead. A combination of presidential and parliamentary elections might brighten politically the dog days of what could be a rainy autumn.