Since 2024, Slovakia has witnessed democratic backsliding and major political unrest. The future of populist nationalism in Slovakia – and Slovakia’s position in Europe – are at stake. John Chin and Daniel Hayase contextualise this unrest, reviewing the challenges posed by Prime Minister Robert Fico’s efforts to consolidate power and to build a bridge between East and West

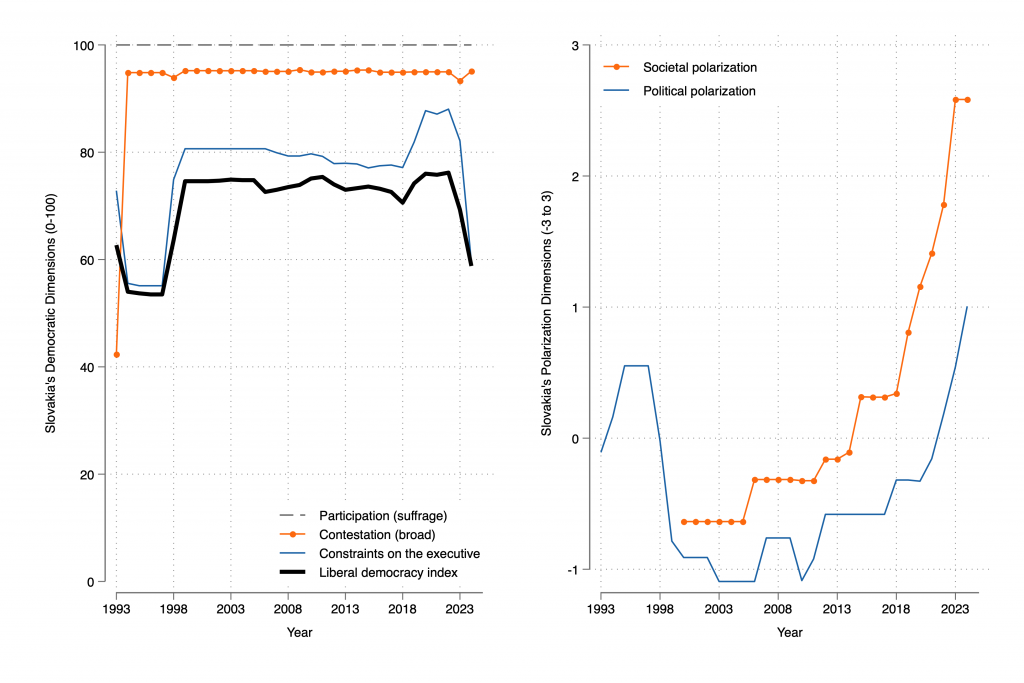

In March, the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project issued its 2025 democracy report. The report placed Slovakia on an autocratisers 'watchlist', judging it one of only three European countries, along with Cyprus and Slovenia, exhibiting early and troubling signs of democratic backsliding. On a scale from 0 to 100, Slovakia’s liberal democracy score fell from a high of 76.2 in 2022 to only 58.4 in 2024, a level not seen since the pre-1998 period.

Electoral participation and contestation remain strong in Slovakia. But constraints on the executive have plummeted since the return of Robert Fico as prime minister in October 2023 at the head of a Smer-SD (Direction-Social Democracy) party-led government. Fico has moved to undermine judicial independence, dismantle the special prosecutor’s office (which had ongoing corruption investigations into Smer-SD politicians), intimidate journalists and restrict media freedom, and attack civil society organisations.

Slovak society and politics have once again become deeply and perniciously polarised, even more so (says V-Dem) than during the 1993–1998 period when Vladimír Mečiar’s populist government first polarised society between nationalists and Europeanists. The latter defeated Mečiar in 1998, paving the way for Slovakia to join the EU and NATO in 2004.

Polarisation has increased since the 2018 murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak, which prompted Fico to resign his second stint as prime minister amid mass protests. The (conservative) nationalist-(liberal) Europeanist divide has only deepened since. The latest Eurobarometer poll, in autumn 2024, shows that 53% of Slovaks expressed trust in the EU, whereas 40% did not.

Slovakia’s social divisions and hostile rhetoric pave the way for political violence and protest. Last May, Fico survived an assassination attempt by a disgruntled 71-year-old Slovak, who claimed to be upset at Fico’s pro-Russian policies and failure to support Ukraine. Luckily, the country has seen little political violence since. An initial wave of Europeanist mass protest against the Fico government’s Russia-friendly policies in late 2023 and early 2024 also abated after the assassination attempt.

Robert Fico's surprise visit to Vladimir Putin in December last year has since triggered waves of pro-European protest

In December 2024 Fico made a surprise trip to Moscow to meet with Vladimir Putin. His visit mirrors Viktor Orbán’s unprecedented trip to Moscow last July, which also contravened EU norms.

Fico's actions have since triggered unprecedented Europeanist mass mobilisation. Protestors decry what they deem to be pro-Russia policies, including halting military aid to Ukraine and threatening to veto further EU sanctions on Russia.

From January to 14 March, ACLED reports over 150 demonstrations have taken place in Slovakia: more than any other three-month period on record since 2020. Since the beginning of the year, protests have taken place every other week under the banner that 'Slovakia is Europe'. One of Slovakia’s largest protests in years, pictured above, drew up to 60,000 people in Bratislava on 24 January. On 7 February, the protests drew some 110,000 people across 41 Slovak towns and 13 other European cities. Similar crowds gathered on 7 March.

Even as protestors have called for his resignation, Fico has moved to shore up his parliamentary coalition. Since 2023, this has maintained a narrow majority (79 of 150 seats) with the support of members from Smer-SD as well as the populist splinter party Voice-Social Democracy (HLAS-SD) and the far-right Slovakia National Party (SNS).

In January, just as Fico had to resort to closing parliamentary proceedings to thwart an opposition attempt to stage a no-confidence vote, he lost his parliamentary majority when several SNS deputies and four Hlas deputies boycotted. Several even demanded cabinet appointments before they would return to vote with the coalition.

In February, Fico negotiated a ministerial restructuring agreement to grant his own Smer party two additional ministries and increase Smer's control to nine ministries. Hlas retained six, the SNS two. Rebel SNS deputies led by Rudolf Huliak then agreed to return to the fold in exchange for Hulak being nominated sports minister. On 19 March, Samuel Migal, a rebel Hlas deputy, was appointed minister of investments and regional development, ensuring Fico retains a parliamentary majority. Another rebel Hlas deputy, Radomir Salitros, becomes a state secretary under Migal.

A state-run poll in February indicated that if parliamentary elections were held today, the pro-European Progressive Slovakia party would win

Fico is no doubt motivated to avoid holding snap elections soon, as Smer-SD has slid in recent polls. Since last autumn, the pro-European Progressive Slovakia (PS) party has held a narrow lead over Smer-SD in Politico’s poll of polls of voting intentions for national parliamentary elections. In February, the first state-run political poll issued in 16 years likewise found that PS would finish first if parliamentary elections were held today.

Fico’s December visit to Moscow was emblematic of his ‘all sides of the world’ foreign policy, which seemingly pivots Slovakia’s foreign policy orientation away from the West. Fico claimed that his primary objective was ensuring continued gas transit through Ukraine to Slovakia, with around €500 million annually in transit fees and access to cheaper Russian gas at stake essential for European economic stability. Fico’s position contradicts the broader European consensus on reducing dependence on Russian energy.

Despite being a vocal critic of Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Robert Fico offered Slovakia as a 'neutral ground' on which to host Russia-Ukraine negotiations

Fico is a vocal critic of Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Zelenskyy has displayed mutual antagonism. Despite this, Fico offered Slovakia as a 'neutral ground' to host Russia-Ukraine negotiations. Russian sharp power and disinformation, meanwhile, has shifted Slovak public opinion to be more sympathetic to Russian positions. A February 2025 poll claims 17% of Slovaks desire Russian victory in Ukraine, compared with only 4% in Poland and 7% in Czechia.

Nevertheless, Slovakia’s key security partners are the United States and Poland, not Russia. Moreover, all its major economic partners lie to the west, including Germany, Italy, and Czechia. Though Fico hopes for Slovakia to become a 'bridge between East and West', his eastward turn has strained relations with Czechia and the EU. Slovakia is at a fork in the road: will it choose the path of Europe and democracy, or will it go its own way?