As we strive towards democratic transformations, we can learn much from marginalised activists. Such activists espouse ‘presentist identities’ to fight the dismissive categories through which other people see them. Presentist identities do not assume a past or a future. Instead, they make us simultaneously perceivable and free, writes Taina Meriluoto

I have followed the lives and political actions of young, marginalised activists in Finland for close to five years now. People with experiences of homelessness, disabilities, mental ill health, addiction and other stigmatising experiences all share one desire. It is a wish for recognition: to be seen and valued as a person, not merely a bundle of bad experiences.

To crave recognition is human. In fact, as Axel Honneth has argued, it is a fundamental prerequisite for our sense of self. We exist only in the warmth of each other’s gaze, and if this gaze is dismissive, our sense of self-worth withers.

Alas, what is equally human is to organise our social world with names, labels and categories. We don’t encounter each other without preconceptions. Rather, we try to figure out the right name and the right box for everything and everyone we encounter. We become perceivable to others through categories.

To tackle structures of inequality and work towards democratic transformations, we need to look at the categories through which we become apprehensible for others

To tackle our deeply rooted structures of inequality and work towards democratic transformations, I believe we need to look at the categories through which we become apprehensible for others. Most of all, we need to understand how contemporary activists fight dismissive categorisations.

My work finds that contemporary activists are adopting what we might call, following Isabel Lorey, ‘presentist identities’. These categories of identity do not assume a past or a future. They are not burdened with predetermined characteristics of how one ought to be, nor by a commitment to remain the same tomorrow. They are applicable only in the here and now, yet they make us perceivable for each other. And they have radical liberating potential from the confines of cruel categorisation.

Sociologist Imogen Tyler coined the concept stigmacraft to understand stigma anew not as ‘spoiled identity’, but as a form of power. She defines it as

a technique of social classification, a governmental strategy of social sorting, a mechanism through which inequalities are inscribed and materialised

imogen tyler, stigma: the machinery of inequality, 2020

At the heart of inequality, then, as Jacques Rancière has also argued, are mechanisms of naming that make it possible to evaluate and organise people.

Sociological literature identifies an abundance of examples where the introduction of new derogatory labels enforces and deepens existing inequalities. Typical are ‘the sink estate’, ‘the benefit brood’, or ‘the undeserving poor’. Names and labels pin down people’s identities. They reduce people to specific experiences, and use this all-encompassing identity to put them in their place.

Stigma, then, affects and works through how we make sense of ourselves. Tyler, quoted earlier, explains how stigma is a form of power where ‘people judge themselves against an incorporated norm and come to anticipate the standards against which they fall short’. We use categories to understand who we are. If other people regard us merely as undeserving poor or a drug addict, we too start to see ourselves as such.

Is, then, the solution, when fighting for a more sustainable, just and democratic world, to discard all names and labels altogether? The activists in my study have a more creative solution.

Increasingly, we produce, negotiate and contest the norms that guide how other people know and understand us in digital environments. We make ourselves in online discussions, and, especially, by performing ourselves visually. We post different images of ourselves and follow how others react to these. Visual social media makes it possible to show others how we see ourselves.

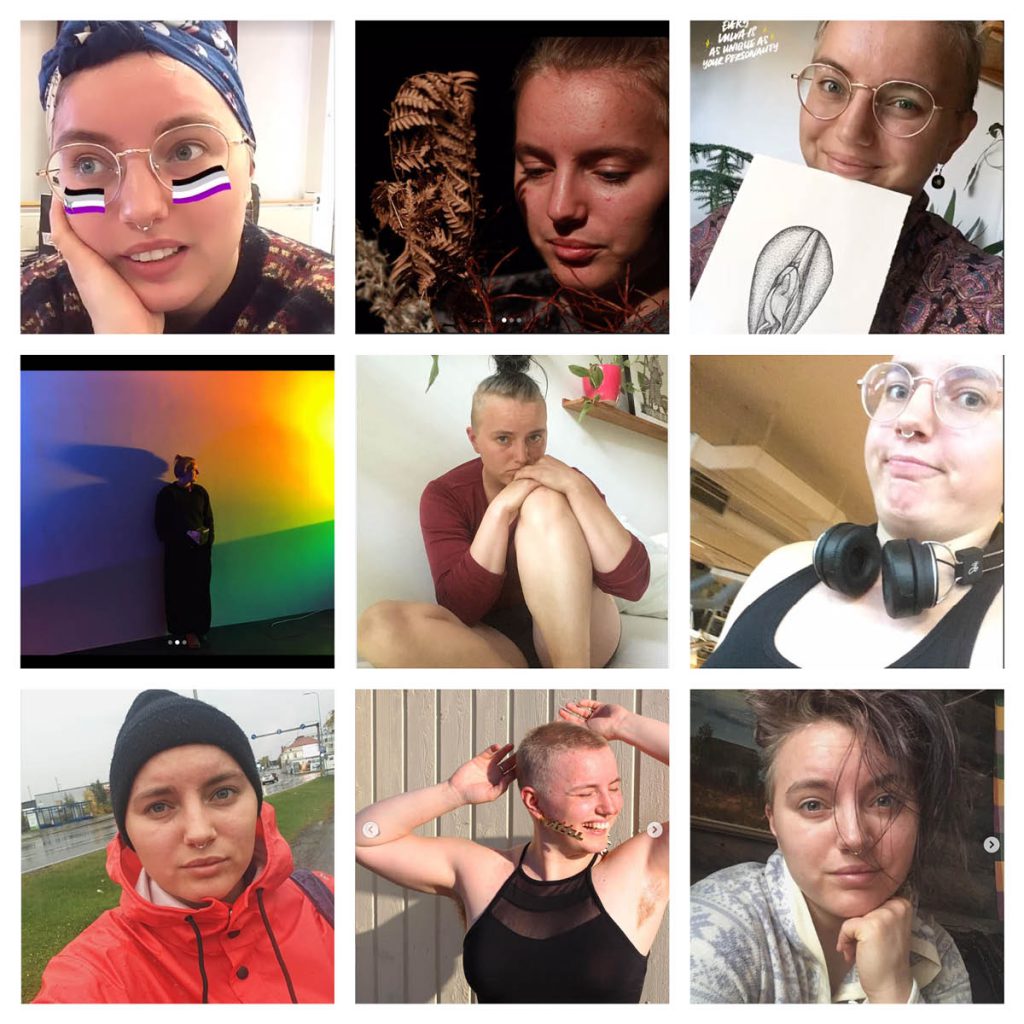

My work analyses how young activists use visual self-presentations for very different purposes, as do we all. Such self-presentations reflect on, and experiment with, how we might be. Through them, we try out different versions of ourselves. We post selfies to gain recognition but, equally, to disturb the frames through which other people see us. On visual social media, we can change from one moment to the next.

In my research, activists perform as multiple 'selves' to disturb the categories that describe them

Hans Asenbaum has suggested that there is radical democratic potential in thinking about the self as multiple and transforming. This becomes tangible in the concrete practices through which the activists in my research struggle to persuade others to see and know them differently. They perform as multiple 'selves' to disturb the categories that describe them. Selfies are the tool they use to strive for recognition, but also in their fight for a more just world – for democratic transformations.

In their self-performances, the activists espouse ‘presentist identities’. Instead of ascribing particular characteristics to a person, these categories, like ‘queer’ and increasingly ‘neurodiverse’, express that you cannot assume anything about their bearer. They clear the slate and argue that the onlooker should meet the person in the here and now, for whoever they might be in this moment.

Activists in my research construct presentist identities visually. They post images of themselves in different roles, with different moods, in different environments. A mental health activist suffering from depression posts a picture laughing with their friends in a bar. They follow it with a selfie from the psychiatric ward. A selfie in which a disability activist wears a sexy corset is followed by a selfie in a lecture hall, then at the grocery store. These activists perform intensely true versions of themselves in the fleeting moment, but free from assumed past and future.

The multiplicity and temporality of these selfies disturb the categories through which we would otherwise be compelled to see the activists. Performing presentist identities problematises the frame in which other people customarily see us. It renders a person less legible, harder to categorise. Selfies documenting a multiple, transforming self can be ‘a means to be known differently’ on a path towards democratic transformation.