Inviting more women to brief the United Nations Security Council helps include them in decision-making on international peace and security. But despite progress, observe Louise Olsson and Anna Marie Obermeier, challenges remain. The Council must integrate recommendations from women's voices into Council decisions

As the struggle over existing norms in multilateral systems has hardened, women’s rights have become a battleground in the UN Security Council (UNSC). In terms of influence and of symbolism, who is allowed to brief the Council can be considered an indicator of women’s inclusion in decisions on international peace and security. Briefing the UNSC is by invitation only. Therefore, this is a situation in which the state holding the monthly rotating Presidency plays a clear role in promoting more balanced and nuanced representation.

Briefing the UNSC is by invitation only – but do women receive these invitations?

European states have decided to promote women’s inclusion in peace and security. But have they followed through in the UNSC? To find out, we looked at public UNSC meeting records on briefers – experts invited to provide testimony – 2015–2021. We can see progress, but important challenges remain.

In January 2022, Norway’s presidency nearly achieved a 50:50 gender balance among the 35 individuals invited to brief the Council. The rotating UNSC presidency has a critical function in promoting improved female representation. The President sets the working agenda and, as part of this, can suggest briefers. Notably, ten or more women briefed the Council during a single presidency for the first time during Spain’s presidency, in December 2016. It took nearly a year – until France’s October 2017 presidency – for the same thing to happen again.

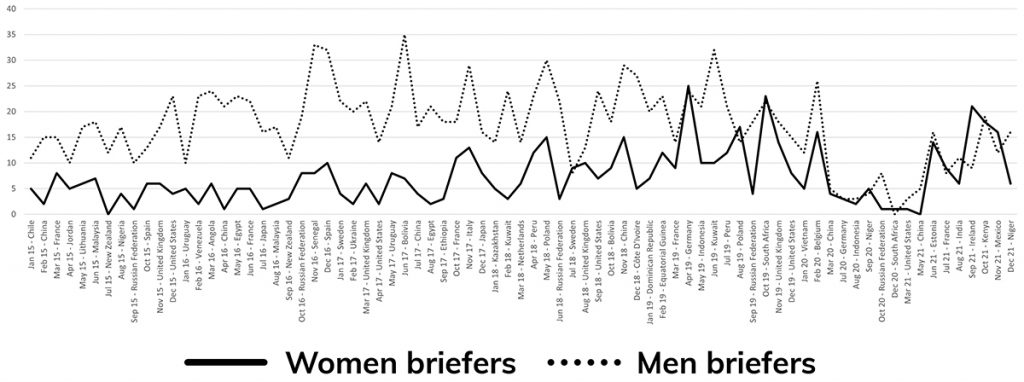

Are these examples exceptions or the rule? Figure 1 shows that some individual presidencies have indeed made significant strides in inviting more women to brief the Council. But this remains an exception to the norm. On average in the 2015–2021 period, each presidency hosted 26 briefers, seven of whom were women; in other words, just 27%.

If we compare by geographical region, on average, 35% of briefers under European presidencies have been women. This is closely followed by African presidencies, where 32% of briefers were women.

With European and African presidencies leading the way, representation has improved over time. Other regions and countries can take steps towards improving their male-to-female briefer ratio, while acknowledging the need to diversify perspectives presented to the Council in other, meaningful ways. In doing so, the Council will receive the best possible information to assess and carry out the work of the various UN agencies, operations, and programmes.

Notably, the Covid-19 pandemic affected the frequency of meetings and the publication of records. We can therefore interpret the information pertaining to 2020 as conservative, representing the minimum number of briefers. However, it does still provide valuable preliminary insights.

Women do not constitute one coherent group; we must also look beyond the gender balance. During its presidency at the 15th anniversary of Women, Peace and Security in 2015, elected member Spain pushed for the inclusion of a section on women civil society briefers in resolution 2242. The Council adopted this resolution in October. Since then, the representation of civil society organisation (CSO) briefers, a group dominated by women, has improved.

At the UNSC, representation of civil society organisation (CSO) briefers, a group dominated by women, has improved since 2015

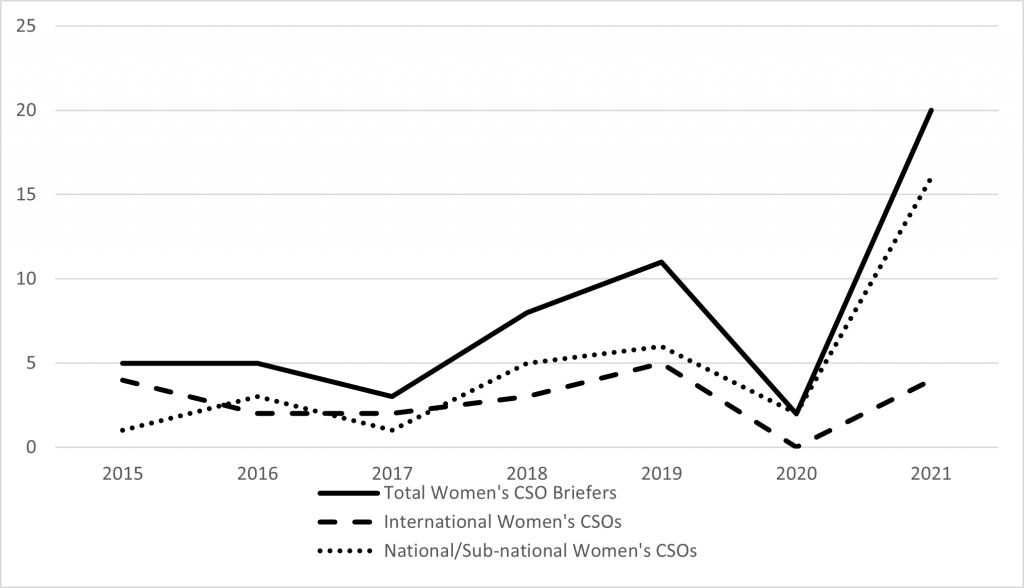

We then looked more specifically at women’s CSOs, meaning those that explicitly seek to improve gender equality or target women. Figure 2 shows that here, too, representation has improved over time. This trend is driven by the Council inviting more National Women’s CSOs. In 2015, it consulted only one National Women’s CSO, whereas in 2021 the Council heard from 14 such organisations. While these groups represent only 3% of all briefers invited between 2015 and 2021, an important take-away from this is that changing imbalanced representation is possible. Similarly, the overall distribution of male-to-female briefers has seen progress in the same period.

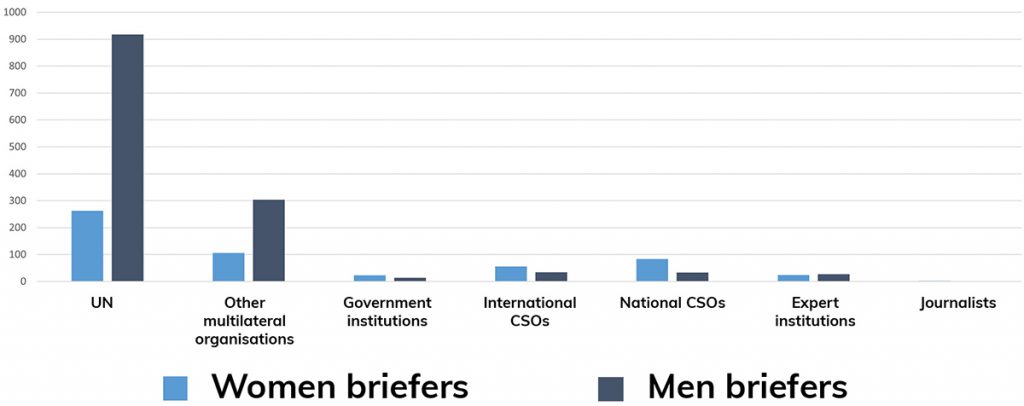

Another area where European states, notably those in the EU, can promote representation, is in the briefers they send to inform the UNSC. We therefore tracked briefers' professional affiliation. Figure 3 shows that briefers from 'Other multilateral organisations' is the largest affiliation category outside the UN. These constitute 22% of all briefers and include organisations such as the African Union, the EU, the International Criminal Court, the League of Arab States, NATO, and smaller multilateral organisations. In this category, male briefers dominate.

Looking specifically at our data on briefers with an EU affiliation, the image of representation is discouraging. 76% of the 148 briefers were men. Men were also consulted on a greater number of issues. The 35 EU-affiliated women who briefed the Council between 2015 and 2021 spoke on twelve different topics. However, this was mostly on international peace and security (on eight occasions) and on women, peace, and security (six occasions).

International norms on gender equality and women’s empowerment are increasingly being questioned as international multilateral systems have come under fire. This should make promoting women’s representation, at an individual and an organisational level, a core component for states seeking to preserve and strengthen the UN and other multilateral institutions. As the data shows, change is still possible. The Council hears from more women and more perspectives from outside of the UN today than it did six years ago.

The Council hears from more women and more perspectives from outside of the UN today than it did six years ago

Moreover, in order to ensure the increasing integration of women’s rights and diverse interests into UNSC decisions, representation is not enough. As the struggle for women’s rights continues, Council members who promote women’s empowerment must strive to integrate the recommendations of women’s CSOs in Council decisions. They must walk the talk in all other multilateral organisations in which they serve.