Social media allows radical political actors to organise at a sub-national level, enabling engagement beyond existing activist cohorts. Thomas Evans analyses this phenomenon by exploring examples from Ireland and the UK

Social media is changing the playing field for radical movements. Platforms like X, Telegram, and Facebook allow outreach and mobilisation at a community level. This enables radical actors to link their ideologies to locally salient issues, and to mobilise previously non-aligned people. It builds legitimacy, recruits followers, and spreads protest.

In July 2024, the murder of three young girls in Southport sparked violent riots in the area. Fuelled by disinformation on social media which claimed the perpetrator was an illegal migrant, unrest quickly went national. In less than a month, anti-immigration violence had broken out in 27 towns and cities across the UK.

There was a strikingly similar pattern to events in Dublin in November 2023 following the attempted murder of an adult and three children. Prior to formal police identification, disinformation circulated on social media that the perpetrator was a Muslim asylum seeker. This mobilised protest events and violence — notably arson — at accommodation earmarked for migrants and asylum seekers. Again, social media was a key organising force in the spread of unrest.

In both cases, far-right activists inside and outside the UK and Ireland stoked the violence. Through mainstream and alternative online platforms, they rapidly disseminated disinformation and coordinated unrest in the immediate aftermath of attacks.

Yet the people involved appear, on the whole, to have no clear connection to extremist movements. In one of the largest protests, in London, while a majority of those arrested had previous violent convictions, 20% had no criminal record, and only 8% had a history of racially aggravated offending.

Ethnically-focused bigotry and racism were central drivers for violence in these examples. But both also show how local communities are vulnerable to targeted messaging by small numbers of activists.

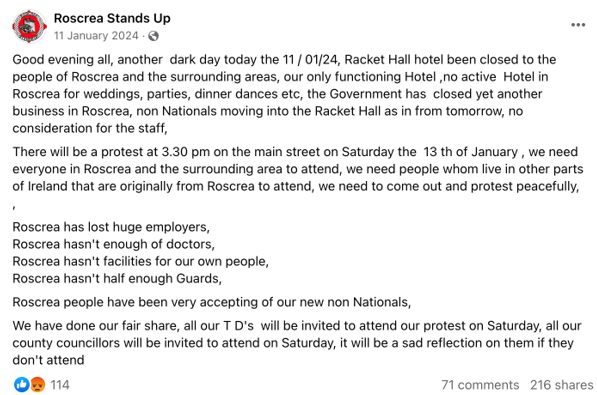

In 2024, deprivation was a significant factor in where unrest took place, and who was charged with offences. A majority of those charged came from the locations in which riots and protests had broken out. In Ireland, housing and infrastructure as well as opposition to migration appears key to galvanising involvement. In rural Ireland in particular, protests are often organised by neighbourhood campaigns like Roscrea Stands Up, comprised of residents whose main concern about migration is its impact on local facilities and resources. But, despite having argued their opposition to any cooption by outside actors, these protest sites do attract far-right agitators, who have in some instances fomented violence.

Local social media also enables effective mobilisation. Many of the 2024 riots were organised by residents posting maps, addresses, and calls to violence on targets in their area. These included mosques in Liverpool and hotels housing asylum seekers in Leeds and Northampton. And though some accounts were tied to extreme-right activists, many inflammatory posts were made by unaffiliated individuals.

Perpetrators of hate crimes tend to act in their local areas, where targets are easier to identify. But radical movements can connect latent local discontent with their own ideological views, and mobilise mass violence. This process is known as frame extension, and social media makes it much easier.

The Irish and British far right continue to use decentralised Telegram channels, Facebook groups, and X accounts to spread resonant messages that mobilise their target audiences. At a national level, the language of 'invasion' and the need to 'fight back' against migrants is tied to rising political discourse around immigration. Local-level messaging often links asylum-seeker housing (and Muslims more broadly) to the 'threat' posed to children. Posts might stoke fears of 'Muslim grooming gangs', declining living standards, and shortages of housing and public services.

The extreme right is a small, fractious movement lacking a significant offline footprint. But social media is also beneficial for radical organisations which maintain more embedded profiles within specific geographical areas.

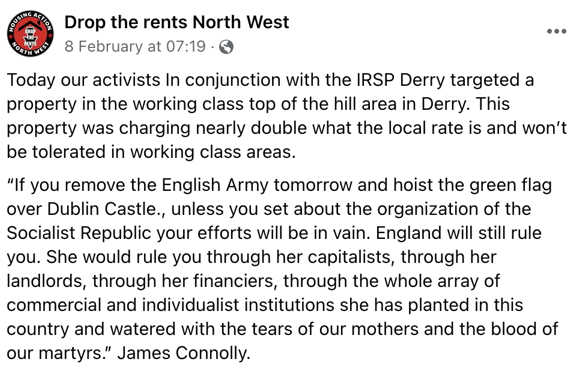

My PhD focused on 'dissident' Irish republican organisations' community activism strategies. These groups attract most attention for their continued use of violence after the 1998 peace agreement. But they also engage in non-violent community activism in working-class Catholic/Nationalist/Republican areas, predominantly in Northern Ireland.

Community activism has a longstanding tradition in Irish republicanism, highlighting state failure and deepening community legitimacy. But dissident groups tend to be small and lack significant support and resources. Local social media, managed and curated by branches at a city and sub-city level, allows such groups to amplify their activism, and to monitor developing community issues. It also enables them to link locally salient issues to republican frames of colonialism and capitalism, disrupting peace process 'normalisation' narratives.

Extreme-right groups in the UK and Ireland appear interested in a similar playbook. In the UK, the leadership of Patriotic Alternative has called for a focus on 'local activism'. The group has drummed up support on social media for community activities like litter-picking in Southport. Media reports suggest the group is attempting to infiltrate local anti-migrant campaigns across the country. Moreover, 'active clubs' — real-world extreme-right groups aimed at young men and focusing on physical fitness and combat sports — are expanding. In Ireland, independent far-right candidates have won election to local councils by focusing on immigration and resonant community issues.

Yet organisations on the extreme right will struggle to break through meaningfully at community level. Their size, and the fragmented nature of their movement, pose practical challenges. And their lack of historical legitimacy, community links, and prior nonviolent, genuine activism discourages local people's receptivity to the cause.

What these groups can do is exploit, on an ad hoc basis, gaps in service provision and community cohesion. We already know how disinformation spreads at an alarming rate through online networks. The threat remains, therefore, that local unrest can rapidly go national, and then local again.

No.39 in a thread on the 'illiberal wave' 🌊 sweeping world politics