Neither Poland's government nor its opposition has a straightforward path toward an electoral majority. Meanwhile, personal conflict between Jarosław Kaczyński and Donald Tusk dominates the news cycle. Piotr Marczyński argues this configuration reflects the shallow roots of the Polish party system, with axes of polarisation gradually realigning along ideological lines

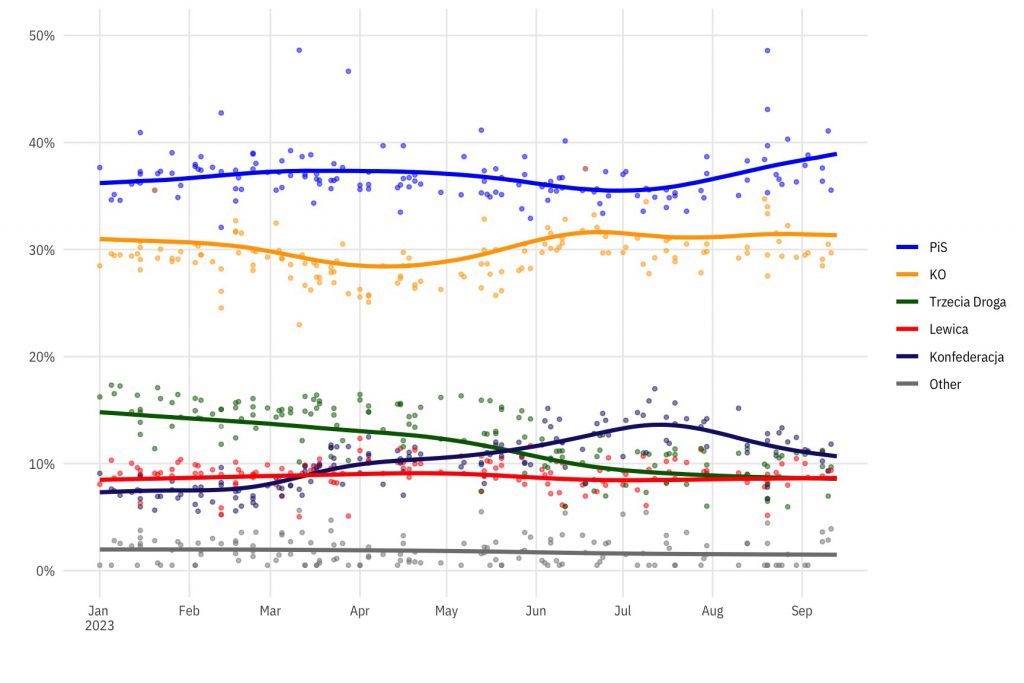

In the run-up to the October parliamentary elections, Polish politics remains as convoluted as ever. The aggregate of polls indicates the governing Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) will win the most votes. However, it will likely fall short of achieving an independent legislative majority of 231 seats. Nor, remarkably, can the opposition find a clear path to the government. Aggregate polling trends show that the ascending Civic Coalition (Koalicja Obywatelska, KO) picks up voters primarily from the centrist Third Way (Trezecia Droga, TD). This leaves the coalitional capabilities of the ‘democratic alliance’ constant.

The extreme-right Confederation (Konfederacja) party thus sits between the government and the ‘democratic alliance’ – making it an unlikely kingmaker. A Confederation-PiS coalition would secure a majority. But its populist bent makes Confederation an unlikely coalition partner. Capitalising on the failure of mainstream politics in the snap election would be more in line with its current strategy.

Beyond Confederation's scepticism, both blocs would prefer to form a government without the burden of an unpredictable partner. PiS hopes to bolster its precarious majority, given that it polls well and has managed to lure a few Confederation MPs to its governing coalition. KO, on the other hand, hopes to ride the wave of anti-government sentiment by organising the March of Million Hearts two weeks before the election.

In an uncertain electoral landscape, the two main parties are stirring up a longstanding rivalry between their two leaders

Clearly, there is no straightforward path to a majority. The possibility of a snap election in spring thus looms large. In this uncertain electoral landscape, the two biggest parties have mobilised the electorate by stirring up a longstanding personal rivalry between their respective leaders.

PiS and KO present this election as a clash of personalities. In a recent poll, 70% of Poles indicated they want a Kaczyński-Tusk TV debate, which, amazingly, hasn't happened since 2007. Back then, Tusk emerged victorious by emphasising how Kaczyński was ignorant of voters' everyday lives. Over the years, their rivalry has shaped Polish politics. Tusk and Kaczyński manage to mobilise their core electorate while alienating everyone else, as shown by their high disapproval rating.

PiS warns that Donald Tusk is merely an executor of neoliberal policies under the influence of foreign powers

PiS's strategy juxtaposes Kaczyński's vision of 'sovereign Poland' with that of Poland under Tusk: an executor of neoliberal policies under strong influence from foreign powers. Tellingly, a recent PiS tweet features a shadowy German Chancellor phoning Donald Tusk to persuade him to raise Poland's retirement age. The Chancellor's call is futile: an implacable Kaczyński contends that 'Poles will determine that in a referendum' because 'Tusk is no longer in office'.

KO, by contrast, claims Tusk's experience in European politics empowers him to develop a future-oriented Poland. The party compares this with the parochial Kaczyński – a politician stuck in the past. KO even launched a billboard campaign featuring Kaczyński with the caption 'I am a threat'. But KO's campaign eventually moved beyond merely highlighting Kaczyński's ignorance to warning of PiS's likely effects on disadvantaged groups.

Clearly, weaponising hostility towards out-party leaders is playing a key electoral role. And the phenomenon transcends the Polish context: negative partisanship drives political behaviour in a variety of country contexts. For example, Joao Areal found that in Brazil, voting against a disliked politician was a more powerful driver than support for a preferred candidate. Areal suggests this phenomenon might recur in any context lacking stable ideological identities. In Poland, the moral conflict over the right to govern trumps ideological disagreements. We can thus say with confidence that the Polish system falls under this category.

Will Polish politics remain defined by the Tusk-Kaczyński conflict? For now, their personal clash dominates the news cycle, and all remaining parties orient themselves towards it. Third Way tries to play the anti-polarisation card by praising consensus-oriented politics. Confederation poses as an anti-establishment force by distancing itself from all other parties.

In this light, it's interesting that the tactic of Lewica (The Left) is to create a new ideological axis of polarisation. During a recent party convention, its leader announced that the party 'needs to serve as a shield against Confederation'. With its campaign slogan My heart is on the left, the party aims to create an identity based on commitment to equality and anti-fascism.

Lewica (The Left) is proving far more popular with young Polish women than with men, reflecting Poland's simmering conflict over reproductive rights

It is unclear whether this ‘mini-polarisation’ will influence the forthcoming election. However, it reflects intensifying societal sentiment. Lewica attracts around 17% of women aged 18–29, yet only 7% of young men. Confederation fares much better (40%) among this group. This gendered split reflects Poland's simmering conflict over reproductive rights. The 2020 abortion ban galvanised thousands of young people into mass protest:

By contrast, 56% of PiS supporters are over 60 years old. PiS is becoming increasingly reliant on retirees for re-election. While the situation is less dire for KO, this party, too, struggles to attract young voters. Moreover, when it succeeds, young people tend to support KO despite its obsession with PiS rather than because of it.

So while PiS and KO currently dominate the political landscape, their predominance may not endure. This obsession with personal conflict between the two party leaders distracts from crucial issues of ideological realignment over gender norms, environmental protection, and state interventionism. Sooner or later, those ideological differences will reshape the axes of polarisation in Poland.