Citizens across Europe identify with Europe in different ways. Those with a civic conception of what it means to ‘be European’ are more supportive of sharing resources across borders. Those that identify with Europe based on religion are much more sceptical, write Nicholas Charron and Monika Bauhr

The EU has launched several large-scale redistributive efforts in response to particular crises. Examples include NextGenerationEU following the Covid-19 pandemic, and the bailouts in response to 2008 financial crises. Such efforts also include more long-term economic redistribution through the EU Cohesion Fund.

Political backlash and controversy surrounding these policies have made policymakers and researchers seek explanations for why people support, or oppose, within-EU redistribution. While supporters stand for ‘solidarity across borders’, opponents argue that their resources are better spent at home.

Supporters of cohesion policy stand for ‘solidarity across borders’. Opponents argue that their resources are better spent at home

We looked at research on individual and country-level factors that might explain this divide. Studies find that factors with an element of self-interest, such as one’s income or occupation, or the wealth of one’s home country, play surprisingly little role. Rather, softer factors such as one’s political values, altruism, cosmopolitanism, or trust in political institutions, appear to matter most.

Among the softer factors, people consider their identity with, or attachment to, Europe, and to their home country, most important. The stronger one’s identity or attachment to Europe, the greater the level of solidarity one is willing to express. Conversely, opponents tend to have a strong national identity vis-à-vis Europe.

Our recent article in the Journal of Common Market Studies challenges this narrative. We distinguish between ‘if’ or ‘how strongly’ citizens identify with Europe, and ‘how’ or ‘why’ citizens identify with Europe. In other words, what does it mean to ‘be European’?

Building on the work of authors such as Michael Bruter and Thomas Risse, we put forward a multidimensional European identity based on civic and religious conceptions.

A civic identity refers mainly to rights, rules and laws that affect all citizens on a day-to-day basis. They also affect citizens’ sense of 'constitutional patriotism'.

A religious identity builds on adherence to the community on the basis of the dominant religion: Christianity. One can think, respectively, of Guy Verhofstadt and Viktor Orbán as defining such European conceptions.

A civic identity refers to mainly rights, rules and laws that affect all citizens. A religious identity builds on adherence to the community on the basis of the dominant religion

The type of identification with Europe influences support for within-EU redistribution. However, it does not necessarily influence how much one sees oneself as European.

Past research shows that domestically, religious identifiers prefer religious institutions to provide welfare services, rather than a secular state carrying out universal, redistributive, social welfare policies. Further, a religious European identity is more exclusive in terms of ‘who’s in or out’ – only Christians are included.

A civic European identity, on the other hand, is less exclusive in terms of determining ‘who is or isn't’ European. This increases the likelihood that such people are willing to share across borders.

Our study is unique because, rather than enquiring about sending aid to other European countries in specific times of crisis, we focus on a mainstay of EU policy that no previous research has studied explicitly: cohesion policy.

Eighty per cent of cohesion funds, representing a third of EU expenditure, goes to citizens living in areas with a GDP per capita of 90% of the EU average or less. These funds totalled €352 billion during the 2014–2020 budget period, indicating that cohesion is indeed a progressive redistributive policy.

We test our idea with an original survey and data funded via an EU Horizon 2020 grant. The survey collects data from 17,147 interviews in 15 countries, representing 85% of the EU population.

First, we gave respondents some background information about cohesion policy. We then measured ’economic solidarity’, by asking respondents whether they supported the policy. Finally, we asked respondents whether they would support their country contributing ‘more’ (if it could), ‘about the same’, or ‘less’ to cohesion.

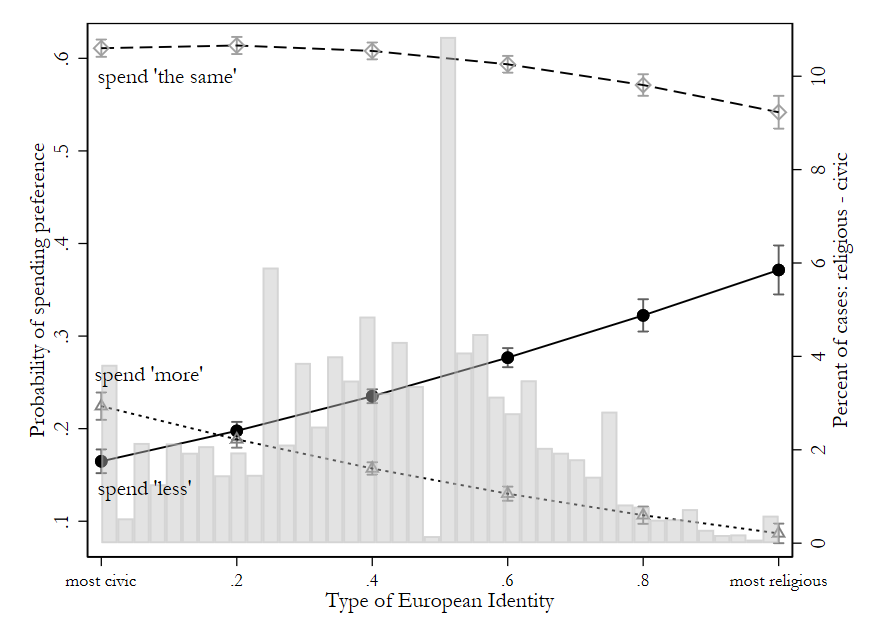

The figure above shows that more than half of respondents would prefer to ‘spend about the same’ (top dashed line). This implies tacit support for the idea (or possibly indifference), depending on the respondent. This is unsurprising, given the low overall awareness about cohesion policy among Europeans.

How one identifies with Europe has a strong effect on economic solidarity. At the left side of the x-axis are the strongest civic identifiers. On the right side are the most religious (the histogram shows the sample distribution).

The most religious identifiers are just over 3.5 times more likely to want to ‘spend less’ compared with ‘spend more’. The most civic identifiers, on the other hand, are slightly more likely to want to ‘spend more’ than ‘spend less’. This effect is exacerbated further, accounting for how strongly one feels European in general.

Making a distinction between civic and religious identity matters considerably in explaining public support for redistributive EU policies

Ultimately, citizens conceive of ‘Europeanness’ in different ways. Making a distinction between civic and religious identity matters considerably in explaining public support for redistributive EU policies. Moreover, measures of ‘self-interest’, or the amount of expenditure on cohesion policy in a respondent’s home region, are mostly negligible.

Our findings show that simply having a strong attachment to Europe is not enough to express economic solidarity with citizens living in other EU countries. The type of identity matters most.

The results contain a lesson for European policymakers and influencers interested in greater economic integration. Although not a ‘quick fix’, efforts to cultivate a European identity around a more inclusive, civic conception, rather than exclusive ideas such as religion or ethnicity, are likely to facilitate greater European cooperation.

This blog is based on research in the authors' recent JCMS article, In God we Trust? Identity, Institutions and International Solidarity in Europe