Tom Johansmeyer contends that the damage NotPetya caused in Ukraine is much smaller than many believe. A closer look at the $560 million in harm caused by that infamous cyber attack suggests that cyber attacks may only be of limited effectiveness. This, he argues, changes how cyber sits in the security environment

The NotPetya cyber attack of 2017 captured headlines and imaginations. Wired called it 'the most destructive and costly cyber-attack in history'. Many have speculated that the damage it caused could have been far worse.

Conducted in 2017 by Russia’s GRU – similar to the US Defense Intelligence Agency – NotPetya was a wiper masquerading as ransomware. Victims received a prompt to pay a nominal amount ($300) to regain access to their systems. The true purpose, however, was to destroy data. NotPetya’s intended victim was Ukraine, where it gained a digital foothold in accounting software company MeDoc. Yet the malware spread quickly, its unintended victims eventually spanning more than 60 countries, including Russia itself.

NotPetya's victims were prompted to pay a nominal fee to regain access – but its true purpose was to destroy their data

NotPetya remains widely misunderstood; the victim of extensive popular reporting. The event has been hyped, hyperbolised, and ascribed an estimated $10 billion economic impact worldwide, which itself begs for contextualisation.

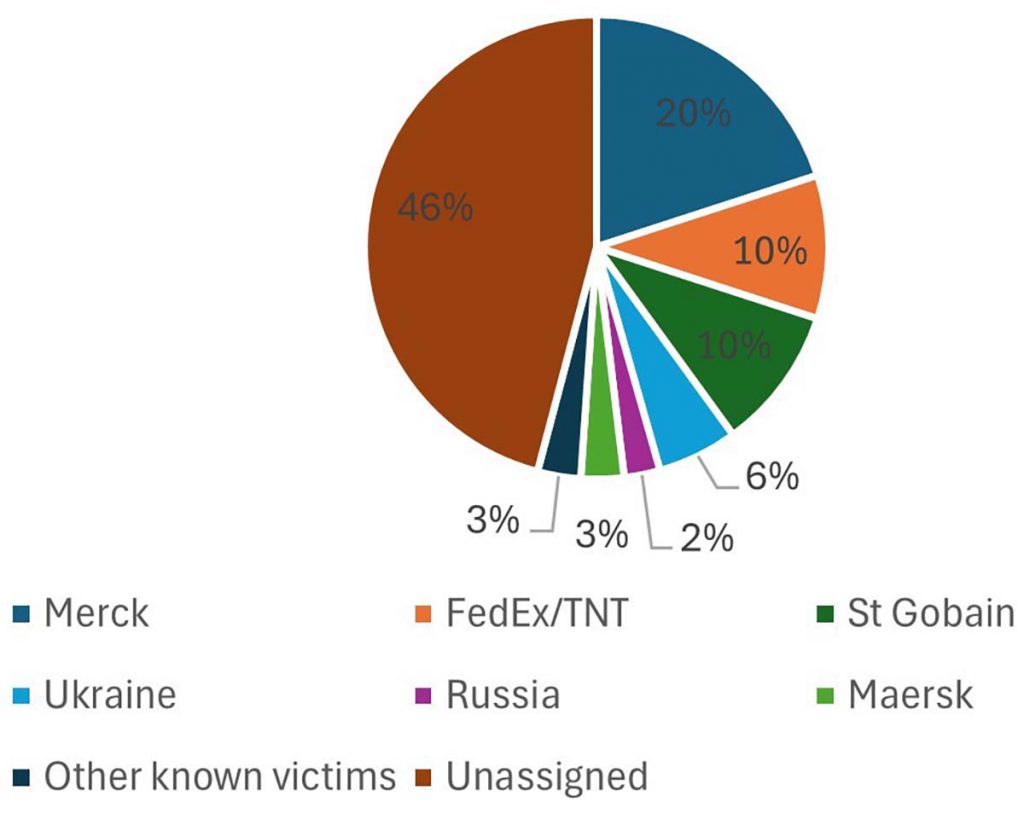

Despite NotPetya's perceived magnitude and importance, discussion has tended to stay at a superficial level. Underlying detail has been probed only periodically. Even then, the focus has tended to stay on large economic impacts sustained by high-profile companies such as Merck, Maersk, and Fedex/TNT. NotPetya’s loss may have been popularly characterised as cataclysmic, but it was in fact a below-average cyber catastrophe. It was also generally ineffective. And while NotPetya's target was Ukraine, most of the damage occurred elsewhere, which leaves a gap in the broader discussion.

The economic effects of the attack on its intended target – Ukraine – could thus benefit from deeper exploration.

NotPetya has been hyped, hyperbolised, and ascribed an estimated $10 billion economic impact worldwide. Its true impact, however, remains widely misunderstood

Experts believe NotPetya caused up to $560 million in economic harm to Ukraine, though that estimate may be on the high side. It takes the upper end of a range of gross domestic product (GDP) impact as a point estimate, which skews our understanding of the utility of offensive cyber operations.

Scholars and researchers have largely accepted 0.5% of GDP as a measure of NotPetya’s impact on Ukraine. This figure featured in the work of Lennart Maschmeyer, which certainly lends the estimate credibility. And as an estimate of the upper end of the economic damage NotPetya caused in Ukraine, it’s effective. As always, though, context is crucial.

Maschmeyer pulls the 0.5% of GDP estimate from a non-profit independent Ukrainian news source: hromadske. However, the original source of the estimate is difficult to trace. The hromadske piece refers to an Associated Press article that no longer seems to be available. In it, Ukrainian finance minister Oleksandr Danyliuk offers the 'boldest assumption' of NotPetya’s impact at 0.5% of GDP. (Translated via Google Translate, the original is за його підрахунками загальні збитки в масштабах країни можуть скласти до 0,5% ВВП.) No further information on methodology appears to be available from Maschmeyer, hromadske, or any other sources.

NotPetya’s numbers may seem quite large: $560 million in local damage (based on the impact to Ukraine’s GDP) and $10 billion overall. As catastrophe events go, however, this figure is relatively small. A useful measure comes from cyber insurance scholars Martin Eling, Mauro Elvedi, and Greg Falco, who set a threshold of 0.2-2% of GDP to gauge the significance of economic loss from cyber attacks.

They did not reach this measure easily, because only two cyber catastrophes since 1998 had caused this much damage. MyDoom in 2004 and SoBig in 2003 led to economic damage exceeding 0.3% of US GDP at the time. It is not possible to isolate the damage by country from cyber attacks occurring more than 20 years ago, and their approach intentionally stresses the model to make a point: 0.2% of GDP is a high bar. NotPetya may have reached it in Ukraine, but not anywhere else.

And in fact, NotPetya may not have reached that threshold even in Ukraine.

According to Danyliuk, 0.5% of GDP was the 'boldest' of assumptions made. With no lower end estimate available, it is of course impossible to determine whether NotPetya may have failed to reach the 0.2% identified by Eling, Elvedi, and Falco. However, if one generously maintains that the event was sufficiently significant that it intuitively must have exceeded 0.2% of Ukraine’s GDP – which itself is a reasonable position – then the economic loss may fall as low as $200 million. Its significance per Eling, Elvedi, and Falco's test is still offset by the fact that the tangible impact was small.

Perhaps that’s the enduring lesson of the economic impact of NotPetya in Ukraine. The worst-case estimate – 0.5% of GDP at $560 million – is manageable. There is, it appears, a limit on the economic harm that cyber attacks can effect, particularly in light of past activity. And by probing the economic impact of the go-to example of cyber operations, it becomes possible to see the limits of even the seemingly most menacing of cyber aggression. The limited economic damage caused by NotPetya suggests that the threat of runaway code may not be as concerning as some believe. This leaves room for the more effective integration of offensive cyber operations into security strategy.

The worst-case estimate of NotPetya's economic impact on Ukraine is 0.5% of GDP, which suggests there is a limit on the economic harm cyber attacks can effect

It is also important to understand scale and avoid hyperbolisation, and that means understanding as clearly as possible the effects of such events as NotPetya. In doing so, though, we should use those insights productively. Cyber attacks can be disruptive, but their effects are also transitory. This can make them an effective temporary alternative to kinetic engagement.