Despite a series of court rulings challenging Japan’s ban on same-sex marriage, public opinion remains largely unmoved. Robert Nordström presents evidence from new survey data which reveals the fleeting influence of judicial action in advancing LGBTQ rights in this conservative society

On 13 December 2024, the Fukuoka High Court ruled that Japan’s ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional. This was the most clear-cut and stringent verdict ever made in support of same-sex marriage in the traditional and conservative East Asian country. Thus, the country seems to have taken another step towards marriage equality.

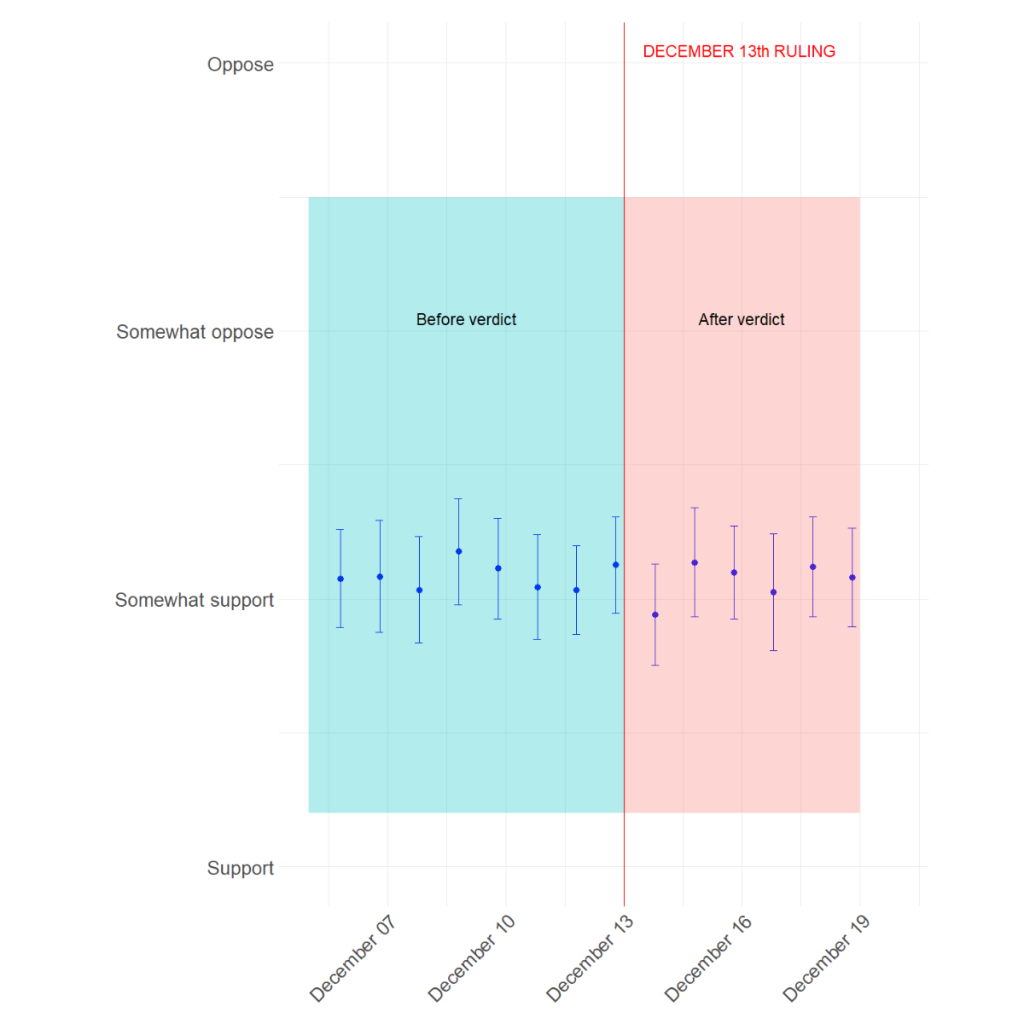

However, the ruling had little effect on Japanese attitudes towards same-sex marriage, as revealed by a survey I conducted in Fukuoka and surrounding prefectures over two weeks before and after the ruling. Through PureSpectrum, I asked 1,331 Japanese respondents, half before the ruling and half after, whether the judicial ruling on same-sex marriage would have influenced their support for introducing same-sex marriage. The results show that a positive effect on same-sex marriage lasted only a day after the ruling.

Japan is currently the only G7 country that does not legally recognise same-sex couples. Recently, a Pew Research report showed that public opinion in Japan has become much more tolerant of sexual minorities. The report even claims that Japan is one of the most accommodating countries in the region. Nonetheless, Japan's government, led by the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), is reportedly staunchly opposed to legislating on this issue. To pursue marriage equality, activists have started using different methods, including judicial action, to achieve their goal of legalising same-sex marriage.

Activists in Japan have started taking judicial action to achieve their goal of legalising same-sex marriage

On Valentine's Day 2019, six same-sex couples from all around the country filed separate lawsuits against the Japanese government. According to Marriage For All Japan, the interest organisation coordinating the legal battle for same-sex marriage, the current ban on same-sex marriage is discriminatory and infringes on equality guaranteed by the Japanese constitution. Japan is not the first country in which activists have resorted to judicial courses of action to achieve marriage equality. Take, for example, the historic Obergefell versus Hodges decision in the United States in 2015.

The recent ruling in Fukuoka is the eighth ruling among these cases so far. With the exception of the ruling by the Osaka local court in 2022, other courts have ruled that the current system is unconstitutional. Thus, we can consider the trend in court rulings to be the judicial system taking a consistent stance on the need for stronger legal protections for same-sex couples. The most recent High Court ruling in Fukuoka was the strongest one yet. It found the same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional under all three constitutional provisions as argued by the plaintiffs: the pursuit of happiness (article 13), equality (article 14), and freedom to marry (article 25). Previous rulings had found only violations of one or two of the constitutional provisions.

The most recent High Court ruling in Fukuoka found the same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional under three constitutional provisions

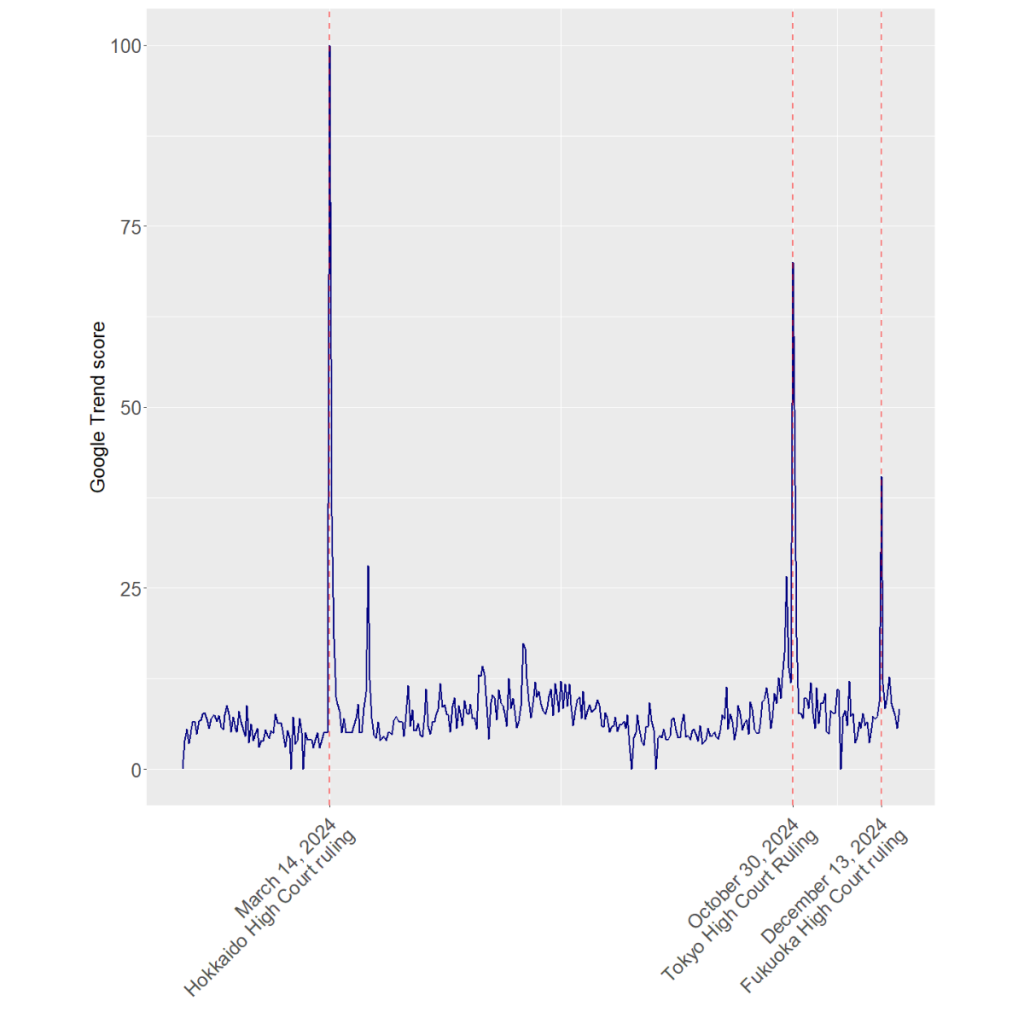

Public and media interest in this ruling was high. Major Japanese media websites such as YahooNews.jp and NHK News reported on the decision as their top story. Even LDP Prime Minister Ishiba was reported as having expressed 'sympathy' for the plight of same-sex couples after the ruling. The Google Trends data below shows that every time High Courts declare their verdicts on this issue, the rulings gather considerable attention, including the most recent Fukuoka decision. The news was widely covered by local broadcasting stations. We can therefore assume that in Fukuoka and surrounding prefectures, most (or at least a large proportion of) Japanese adults have heard about the ruling.

However, the ruling's effect on public approval of same-sex marriage was much less impressive. In the initial hours, respondents strongly favouring same-sex marriage increased to 40% from 26% before the ruling. This effect had already dissipated within 24 hours of the verdict. The ruling seemed to affect public opinion regarding same-sex marriage only in the immediate aftermath of the ruling. As the graph below shows, even one day later, the effect was close to zero.

The ruling seemed to affect public opinion regarding same-sex marriage only in the immediate aftermath of the ruling, and had no lasting effect

We must thus conclude that the ruling had no lasting effect on public opinion. Knowledge about the ruling also seemed to fade quickly after the verdict. Many respondents were unaware the ruling had even occurred just a few days after the event. The number of respondents who were at least somewhat supportive of same-sex marriage was 68.4% compared with 72.6% in a 2019 poll conducted by Marriage for All Japan. This shows that previous rulings have also failed to produce long-term changes in public attitudes.

This recent episode in Japan is at odds with previous research on public opinion. Studies by Andrew R. Flores and Scott Barclay and Margaret E. Tankard and Elizabeth Levy Paluck showed judicial rulings to be instrumental in bringing about changes in the level of tolerance towards sexual minorities. The evidence from Japan shows that judicial action alone seems insufficient for influencing public opinion, especially in the long run.

Judicial rulings do sometimes trigger shifts in public attitudes toward social policies. However, in Japan, supporters of same-sex marriage have little reason to be optimistic. They must recognise that winning the ongoing legal battles may not influence broader societal attitudinal shifts. It is possible, of course, that knowledge of the court rulings has not yet reached enough of the populace to have a noticeable effect. It may also be the case that people do not yet see or understand the purpose of the lawsuits. As several cases are currently being appealed to the Japanese Supreme Court, we should continue to monitor the system.