The 2023 Dutch general election has given Geert Wilders’ far-right Party for Freedom a landslide victory. Iris B. Segers argues that centre-right parties have contributed to the mainstreaming of Wilders’ far-right views and are now trapped in a dance over the formation of a new government

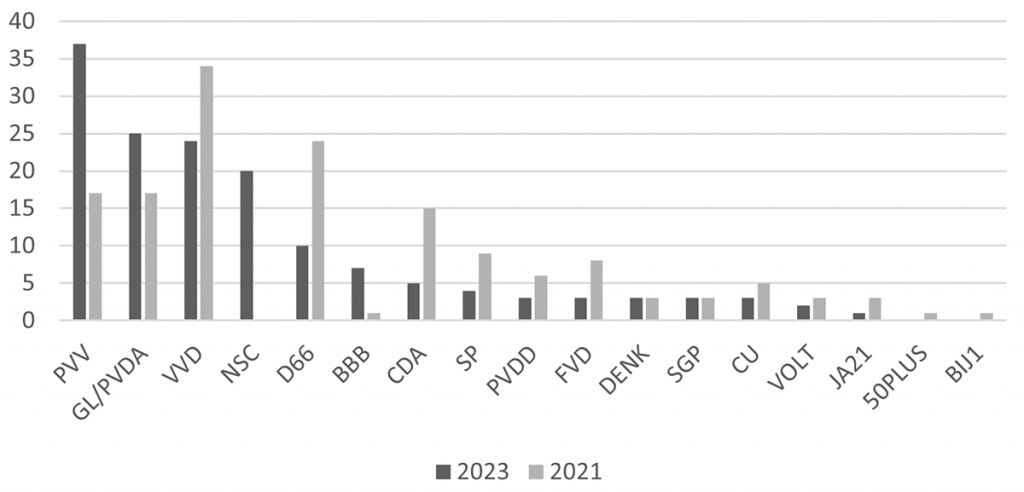

On 22 November 2023, the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV) celebrated a landslide victory. In so doing, it became the largest party by far in the Dutch political system, with approximately 25% of the popular vote, or 37 out of 150 seats. This was a resounding defeat for PVV's three main rivals: the coalition between the Green Left (GL) and the Labour Party (PvdA) (17%), the liberal-conservative VVD (16%), and the three-month-old party New Social Contract (NSC), led by former Christian Democrat Pieter Omtzigt (13%).

Now that the dust has settled, it's clear that PVV party leader Geert Wilders faces an uphill struggle in his early attempts to form a coalition government.

Wilders’ victory is the byproduct of over a decade of undemocratic liberalism under four Cabinets led by VVD's Mark Rutte, whose tenure was tainted by numerous scandals. These included the notorious child benefit scandal, in which the government wrongly accused more than 20,000 families of tax fraud. The Rutte administration ignored early warning signs, and failed to share crucial information with parliament. Despite repeated promises, the Dutch government has been slow to compensate the families affected.

Long-standing voter dissatisfaction over rising poverty, along with the lack of affordable housing, education, and healthcare, have all contributed to low trust in politics among the Dutch electorate. Indeed, the (dys)functioning of Dutch politics has become a core voter issue. In July 2023, Rutte's coalition government collapsed, following bitter disputes on asylum policy. This further favoured Wilders' PVV, which is a key issue owner on immigration.

The recent collapse of Rutte's coalition government over asylum policy favours Wilders' PVV – a key issue owner on migration

In the final days of the election campaign, Wilders radically changed his tone. He downplayed his anti-Islam agenda and argued that 'the priority now clearly lies on other issues in the coming governmental term'. During the final election debate, Wilders expressed his wish to be 'a Prime Minister for all Dutch people'.

Just days before the election, 75% of the electorate remained undecided on how they would vote. It now seems that a week of moderate talking was enough to persuade many to vote for the PVV.

Reactions to Wilders’ victory by the three other largest parties have varied. Green Left/Labour stated that collaboration with PVV is a clear no-go. After previous claims they would not exclude the PVV in advance, VVD-leader Dilan Yeşilgöz has now suggested potential support for, but no participation in, a PVV-led government. NSC has stated it is not yet ready to negotiate with Wilders.

The relatively new Farmer Citizen Movement (BBB) gained seven seats in parliament. BBB has expressed a preference for joining a coalition government with PVV, VVD and NSC. Party leader Caroline van der Plas claimed that 'many voters chose a milder Geert' and that Wilders should drop plans, such as closing the borders and leaving the EU, that are 'definitely impracticable and unattainable'.

To form a coalition government, Wilders would need to relinquish most of his manifesto pledges

Based on earlier statements by VVD and NSC, it does seem that Wilders would need to relinquish most of his electoral manifesto pledges in order to form a coalition.

Indeed, the PVV manifesto is a far cry from Wilders’ claim that 'the PVV is for everyone'. It argues that 'our culture, and Western way of life, is being threatened by allowing entry to large numbers of people, often from non-Western, Islamic countries'. It also claims that 'schoolchildren are being indoctrinated by climate activism, gender madness and with a sense of shame about the history of our country'.

The manifesto advocates banning headscarves in governmental buildings, including parliament. It proposes withdrawing previous apologies for historical slavery, and incorporating 'our Jewish-Christian and humanist roots' as the 'dominant and leading culture' into the Dutch constitution.

Recently, Wilders paid a visit to the Kijkduin neighbourhood in the Hague, to support protesters against asylum seekers. His visit has already raised some eyebrows among potential coalition partners.

The government formation process is now underway. However, the first coalition ‘scout’, PVV senator Gom van Strien, had to step down over allegations of fraud. He has been replaced by the newly appointed former Labour minister Ronald Plasterk. Like BBB-leader van der Plas and Wilders himself, Plasterk has positive views on forming a PVV-VVD-NSC-BBB coalition. He even expressed his expectation to fulfil his task within a week. At that point, the next phase, in which potential partners negotiate the terms of a coalition agreement, would commence.

The PVV is not the only far-right party in town. Rivalry on the far-right side of the Dutch political spectrum is intense, and characterised by substantial inter-party ideological differences.

Thierry Baudet’s Forum for Democracy (FVD) remains in parliament, with three seats. FVD splinter party JA21 also managed to hold on to one seat. Regardless of their size, we should not underestimate the impact of such parties, particularly the extreme-right FVD. The party’s openly racist, antisemitic, transphobic and conspiracist discourse does not only have a platform in parliament. Just weeks ago, the FVD proudly reported that it was the only party to oppose the JA21 motion that 'antisemitism has no place in the Dutch parliament'. FVD also contributes to the mainstreaming of the PVV as a seemingly 'moderate' alternative on the far right of the Dutch political spectrum.

Scholars argue that the far right has gone mainstream. The Netherlands is a case in point: there, centre-right parties have failed to provide a viable political alternative

Scholars have argued for some time that the far right has gone mainstream. The Netherlands is a case in point. Centre-right parties have failed to provide a viable political alternative in times of instability and financial precarity, and have slowly mainstreamed nativist, far-right positions on immigration and national identity. Now, they must decide on whether to join Wilders in a majority government or let him lead a minority government. Unfortunately, either scenario might bolster support for the far right yet further.

This blog piece is a revised and updated version of the original posted on RightNow!, hosted by the University of Oslo's C-REX Center for Research on Extremism