Only populist parties fight elections using anti-corruption slogans, right? Wrong. Sarah Engler finds that other parties too, sloganeer in this way – many without any reference to the ‘corrupt elite’

Populist leaders and parties accuse established political actors of dishonesty and serving their own interests. They address voters who already lack political trust, and they nourish this distrust by presenting the entire political establishment, independent of political orientation or political record, as a corrupt network preserving its own power. Anti-corruption claims are therefore often seen as one expression of anti-elite, populist sentiment. Indeed, the most widely used definition of populism is of a thin-centred ideology that divides society into two homogenous groups – ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’.

Anti-corruption claims are often seen as one expression of anti-elite, populist sentiment

This is not to suggest that corruption is not a real and serious problem. It is detrimental to economic prosperity and social trust, reduces tax revenues, leads to higher inequality and poverty, undermines political legitimacy and thus erodes trust in political institutions. Many European democracies, such as Spain, Italy and Greece, along with almost all post-communist countries, rank high in the yearly Corruption Perception Index released by Transparency International.

And a majority of their populations (80 percent or more) perceive corruption as a widespread problem. In Romania, Slovakia, or just recently in Bulgaria, thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest against the high levels of corruption in their countries.

Seen from this perspective, it is hardly surprising to find populist parties running with anti-corruption election campaigns in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe (e.g. Jobbik in Hungary, ATAKA in Bulgaria, and Podemos in Spain).

But does the conventional wisdom stand up to scientific scrutiny? Do populist parties really politicise corruption more than others?

A study of 170 national party election campaigns in Central and Eastern Europe does indeed reveal that new and opposition parties have a higher propensity to campaign on anti-corruption, and to link it with anti-establishment rhetoric.

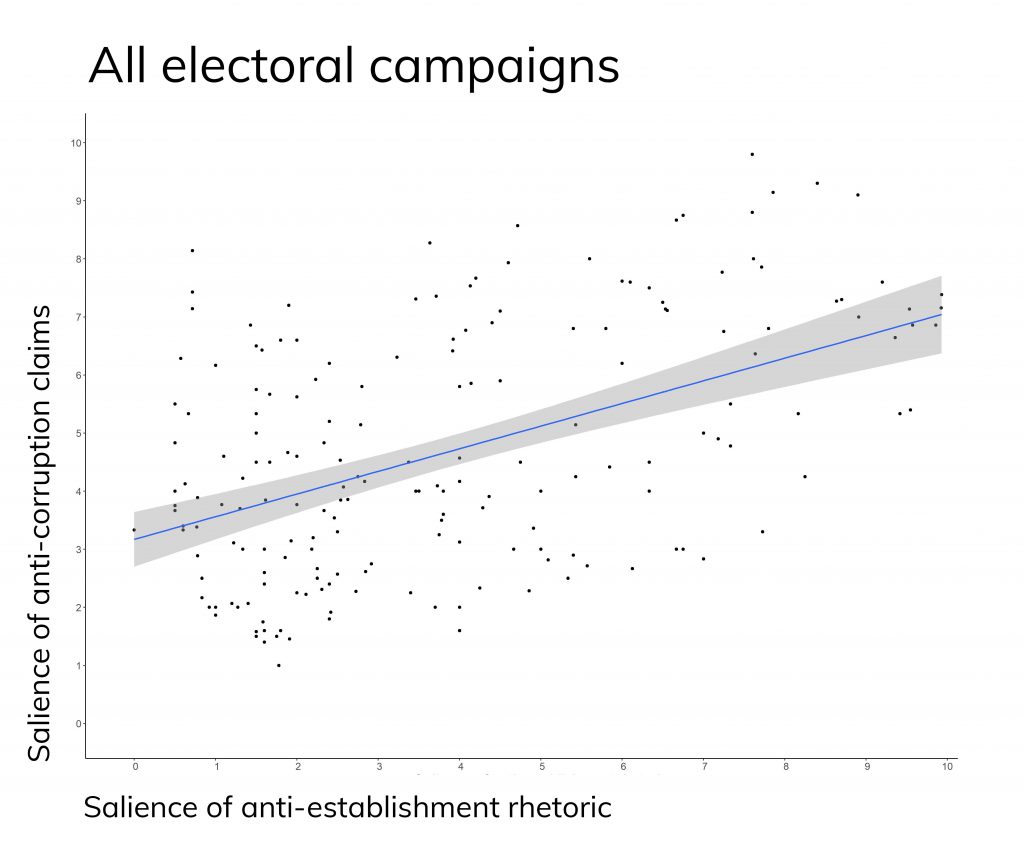

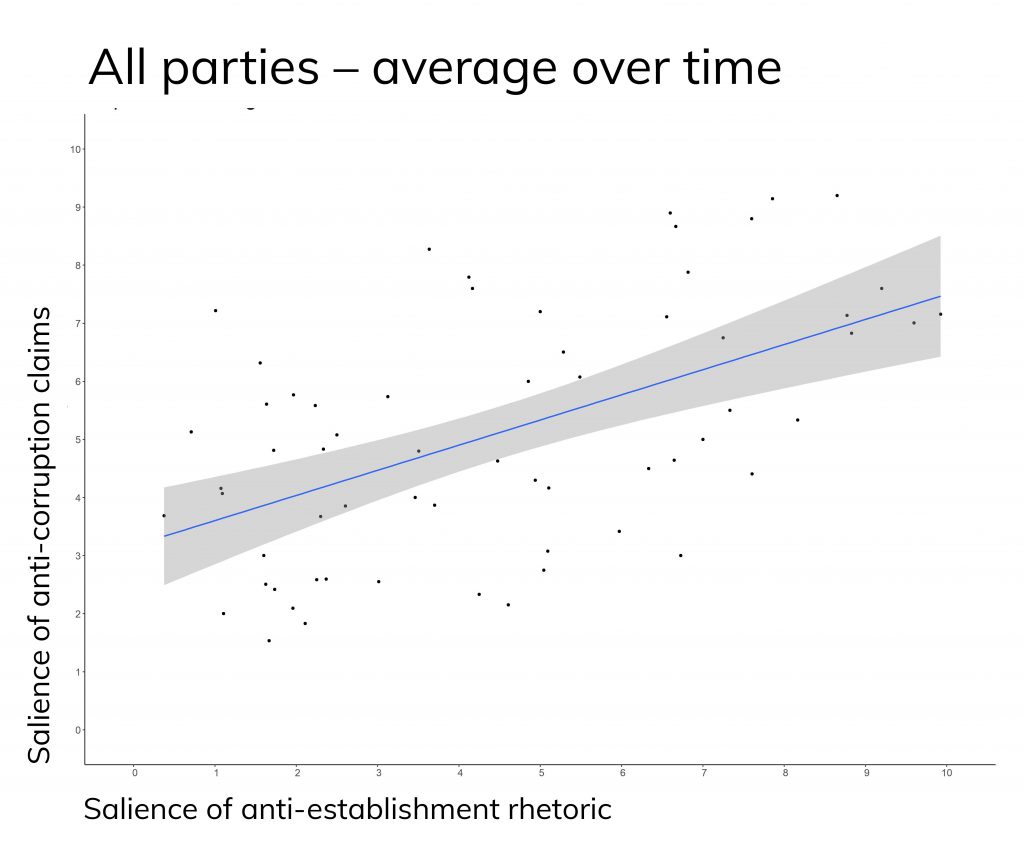

Figure 1 illustrates how anti-corruption claims (x-axis) correlate positively with anti-establishment rhetoric (y-axis). The left panel shows all electoral campaigns, the right presents average values for all parties between 2000 and 2016. The parties talking about corruption range from the populist radical right ATAKA in Bulgaria, to so-called centrist anti-establishment parties (which, apart from their criticism of ‘the corrupt elite’, do not differ from the established parties), to radical left parties such as ZDLE in Slovenia.

not all anti-corruption campaigns are by populist parties

But not all anti-corruption campaigns are by populist parties. Another sizable number of parties politicises corruption but refrains from any anti-establishment rhetoric. Ideologically, these parties are all on the pro-European and economic right of the political spectrum. This is not surprising given the strong anti-corruption message of international organisations such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and the European Union. There are, therefore, strong incentives for these parties to appear competent in the fight against corruption.

Figure 1: Salience of anti-establishment and anti-corruption claims in parties’ electoral campaigns between 2000 and 2016 (N=170; r = 0.48; N = 62; r= 0.54)

Many parties talk about corruption: non-populist and populist ones, parties with radical political stances, and those that promote the European idea and a strong market economy. This suggests that the reasons for parties emphasising the issue of corruption vary as well. Many are successful with this strategy and become powerful political actors in their country. A good example is the anti-corruption party OL’aNO that won the Slovak national parliamentary elections and now leads a governing coalition with several other parties which had politicised corruption in the past.

The electoral success of these parties does not mean that anti-corruption measures always follow. In the past, we have seen parties politicising corruption, which then themselves became targets of corruption accusations.

The Slovak party Smer, once an anti-corruption party, had long stopped talking about corruption before OL’aNO appeared on the political stage criticising Smer’s corruption record. Others, such as the Latvian New Era party and the populist radical right Law and Justice in Poland, have upheld their anti-corruption image, at least in their early years, thanks to efforts to strengthen the fight against corruption and in the absence of big corruption scandals. Yet corruption is still high in these countries, and political trust remains low. As a result, parties promising to fight corruption tend to be replaced by even newer parties promising precisely the same.

Political parties that want to portray elites as evil can easily exploit the issue of corruption. But anti-corruption claims are not limited to populists. Other parties, too, promise to fight corruption – many without even referring to the ‘corrupt elite’. The reasons parties politicise corruption, and why they then often fail to deliver, are thus likely to be manifold.

If we want to better understand the conditions under which political parties live up to their anti-corruption promises, it’s time to ditch conventional wisdom. If we don’t, people may tire of voting on an anti-corruption ticket – and may eventually turn their backs on democratic politics altogether.