The public and the media increasingly use Democratic Global Performance Indicators (GPIs). But how good are these indicators at measuring democratic health? Nicolás Palomo Hernández looks at the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index as an example. He argues that the Index has methodological and ideological biases, yet significant impact nonetheless

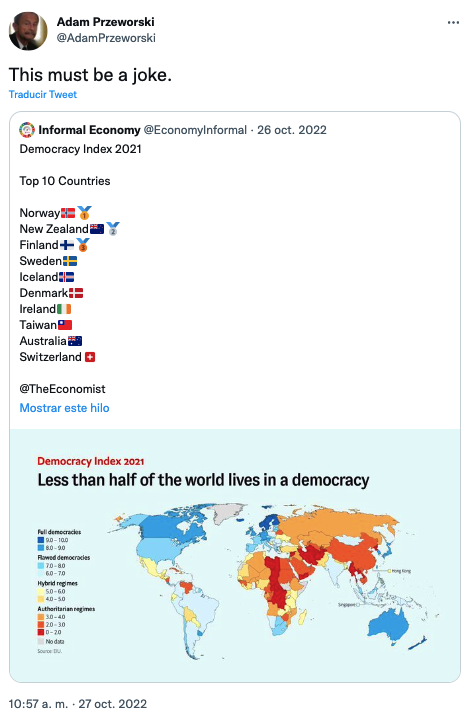

‘This must be a joke.' So reacted well-known political scientist Adam Przeworski to the findings of the 2021 Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index.

But why?

The literature on global performance indicators (GPIs) shows how the Democracy Index promotes a gradual, partially substantive and inherently liberal understanding of democracy. It wields agenda-setting power through socially driven demands.

Kevin E. Davis, Benedict Kingsbury, and Sally Engle Merry define GPIs as

a named collection of rank-ordered data that purports to represent the past or projected performance of different units generated through a process that simplifies raw data about a complex social phenomenon

Davis, Kingsbury, and Merry, Global Governance by Indicators, OUP, 2012

As David Nelken puts it, in their aim to simplify, quantify, and standardise social phenomena, GPIs present themselves as credible, legitimate, objective and neutral. For this reason, with the aim of delivering scientific rigour, the Democracy Index devotes several pages of its annual report to developing the methodology used to construct it. The Index assesses sixty indicators in five categories:

Some indicators are evaluated in a dichotomous way: 0 or 1; others in a three-point scoring system: 0, 0.5 or 1. Building on the sum of the respective indicators, the Index constructs a 0 to 10 scale for each category. The final Index is simply the average score of the five categories. Finally, the Index groups states into four different regime types according to their final score. It then ranks these in descending order according to their democratic quality: full democracy, flawed democracy, hybrid regime, and authoritarian regime.

However, there is only one reference to the process of assessing such indicators: 'in addition to experts' assessments, we use, where available, public-opinion surveys'. This begs the question: how many experts do these surveys consult? What are their backgrounds, and how do their political perceptions influence the assessment of democracy? This is Peter Tasker's main objection. He criticises the use of 'anonymous experts' and defines the methodology of the Index as 'flawed'.

Nelken and Merry argue that GPIs are 'political creatures'. They encourage depoliticising the phenomena they seek to measure, replacing value judgements with high quantification. In this respect, Debbie Collier and Paul Benjamin, Alexander Cooley and Gaby Umbach theorise that GPIs promote a neoliberal agenda or demands to increase rationality and accountability in the public sector by promoting new public management techniques. In the case of the Democracy Index, such a thesis is not hard to believe. The origin and editorial stance of The Economist is openly liberal and, more specifically, advocates for free trade.

According to Debora Malito et al, the ‘embeddedness of power relations’ in GPIs' construction is clear from the biased selection of their indicators. In the case of the Democracy Index, for example, no indicators concern social protection and social welfare or outcome-based economic equality.

The Democracy Index lacks any indicators concerning social protection and social welfare or outcome-based economic equality

The annual report acknowledges that the Index 'does not include other aspects which some authors argue are also crucial components of democracy, such as levels of economic and social wellbeing'. However, it does consider indicators typical of a broadly liberal view of democracy. These include 'Perception of democracy and the economic system; proportion of the population that believes that democracy benefits economic performance' or 'Extent to which private property rights are protected and private business is free from undue government influence'.

Furthermore, in its annual report, the Democracy Index outlines the ongoing debate regarding the lack of academic consensus on how to measure democracy. The report also accepts that its methodology leads to a particular understanding of democracy. Following from this, the Index promotes a rather gradual (non-dichotomous) and partially substantive methodology.

Judith G. Kelley and Beth A. Simmons argue that GPIs shape global governance without the need for specific directives or legislation. GPIs can promote voluntary compliance with certain requirements with minimum external enforcement. Similarly, Cooley argues that GPIs exert normative pressure on states by promoting specific outcomes. Two perspectives can explain states' response to GPIs:

Political science scholars do not often use the Democracy Index. However, it features prominently in the media and is widely consulted by the general public. It shapes global governance by exerting pressure on states through socially driven demands. Thus, it conditions states' reputation in the media and social spheres.

Despite being little used by political scientists, the Democracy Index shapes global governance by exerting pressure on states through socially driven demand

According to Nelken, organisations use GPIs to boost their image by publicising them in the media. The Democracy Index, for example, is made by a private media company whose main product is The Economist magazine. This suggests that diffusion and agenda-setting – rather than triggering direct state response – are its main purpose. Indeed, Cooley emphasises GPIs' importance as powerful agenda-setters in a global and transnational fashion.

The main outcome of the Democracy Index is the creation of a ranking structure among states on the basis of their democratic quality. According to Kelley and Simmons, such rankings trigger mechanisms of competition between states and activate transnational institutional and social pressures. Similarly, Cooley argues that GPIs reshape political relations at national and at transnational level.

In the case of the Democracy Index, national and international media cover major changes in regime type. This sets the agenda and shapes the national political debate. Thus, despite its flawed methodology and ideological bias, the Democracy Index can indeed shape perceptions of democracy around the world.

Hi just to know if you can share with us the indicators you use to evaluate the democracy of a country. I saw that you have 60 indicators so we can not understand haw a country can have 0 point on electoral process and pluralism or on the functioning of government.