There is a national radical right populist presence in almost every Western democracy, but not in Ireland, despite all the amenable conditions for its emergence. Why? Anna Guildea argues that the answer may lie in Ireland’s industrial history

The surge of the radical right across Europe and North America over the past decade has been attributed by many to the fallout of the 2008 Great Recession. Yet if this is the case, what happened to Ireland? Though widely regarded as one of the worst-affected countries in Europe by the recession, there is little evidence of Eurosceptism or anti-immigrant sentiment in its government.

Even before 2008, conditions in Ireland – including rising immigration, increased inequality, job displacement, and a weak left-right divide – were generally considered to be favourable to the emergence of populist parties of the right.

Though widely regarded as one of the worst-affected countries in Europe by the recession, there is little evidence of Eurosceptism or anti-immigrant sentiment in Ireland's government

Despite the extremity of Ireland’s economic collapse, the harsh austerity imposed by the European Union, and the fact that Ireland’s so-called ‘recovery’ has taken place almost exclusively within the ICT sector, in which over a third of those employed are non-Irish, the radical right has had no impact in electoral terms.

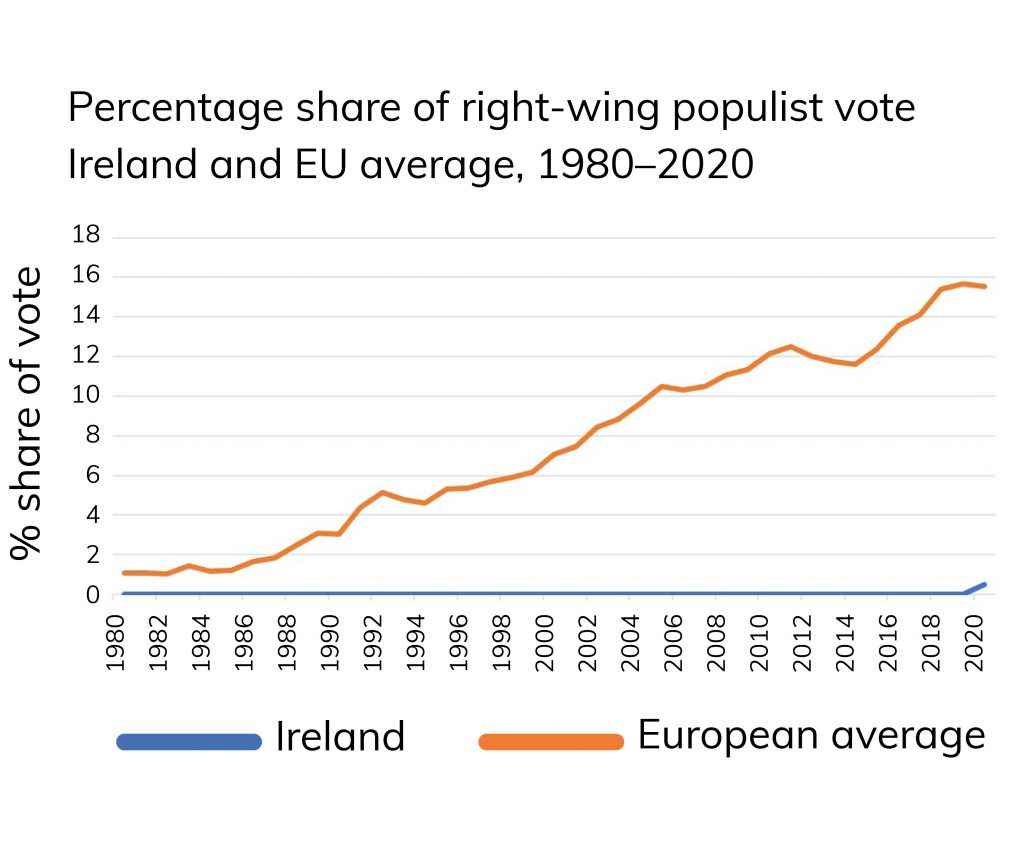

On the contrary, Ireland has, over the years, maintained an overwhelmingly pro-integrationist attitude toward the EU. The 2020 General Election witnessed an unprecedented success for the left-wing Sinn Féin, and a crushing defeat for the nascent far-right Irish Freedom Party (which won less than 0.3% of first-preference votes and no seats in the Irish parliament).

The explanation for Ireland standing out as an anomalous case lies, in part, in the country’s industrial history.

The ‘typical’ voters of radical right populist parties in Western Europe are male, blue-collar workers with no university education. The ‘losers of globalisation’ theory proposes that populism’s rise is primarily due to declining manufacturing bases in Western democracies.

Certain segments of Western society are left ‘economically dislocated’ as low-skilled labour from manufacturing and industrial sectors are outsourced with cheaper labour from the global South.

The former, so the theory goes, are especially susceptible to populist appeals to their ‘economic anxieties’, emphasising the negative consequences of globalisation.

Ireland, however, never had the opportunity to adhere to ‘traditional’ manufacturing export-led models of growth. As a British colony, Ireland underwent phases of de-industrialisation through parliamentary acts as part of wider efforts to protect British domestic industry and to preserve Ireland as a source of primary agricultural commodities.

For example, the 1699 Wool Act effectively killed the then-superior Irish wool industry. As a result, Ireland was extremely late in developing an industrial sector following its independence.

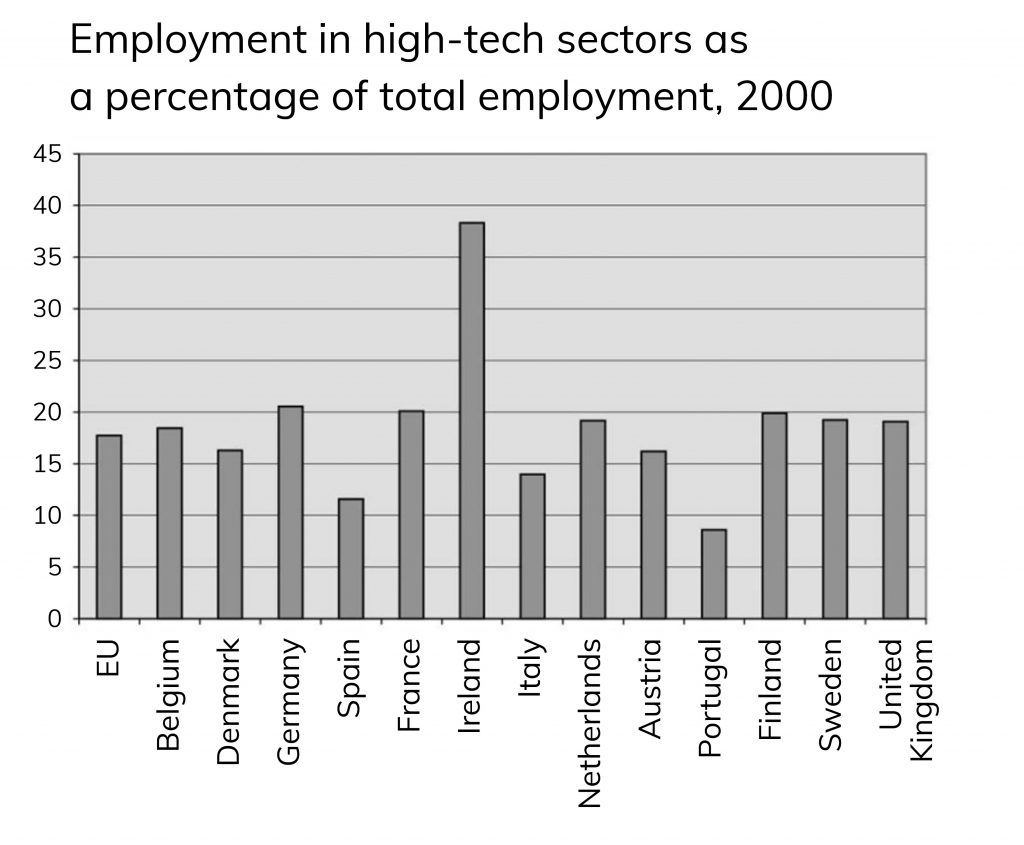

It began the process of opening its economy during the late 1950s, with a strategy of prioritising support for the development of high value added market niches, including electronics, chemicals, pharmaceuticals and medical devices, in which projects were internationally mobile.

The state’s policy was unique in attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) – to which most European countries at the time were indifferent. Ireland has since experienced phenomenal growth of export-oriented FDI in manufacturing, from a zero base in the 1950s to a situation by 2016 where 71% of output and 57% of employment in the industrial sector was in foreign-owned firms.

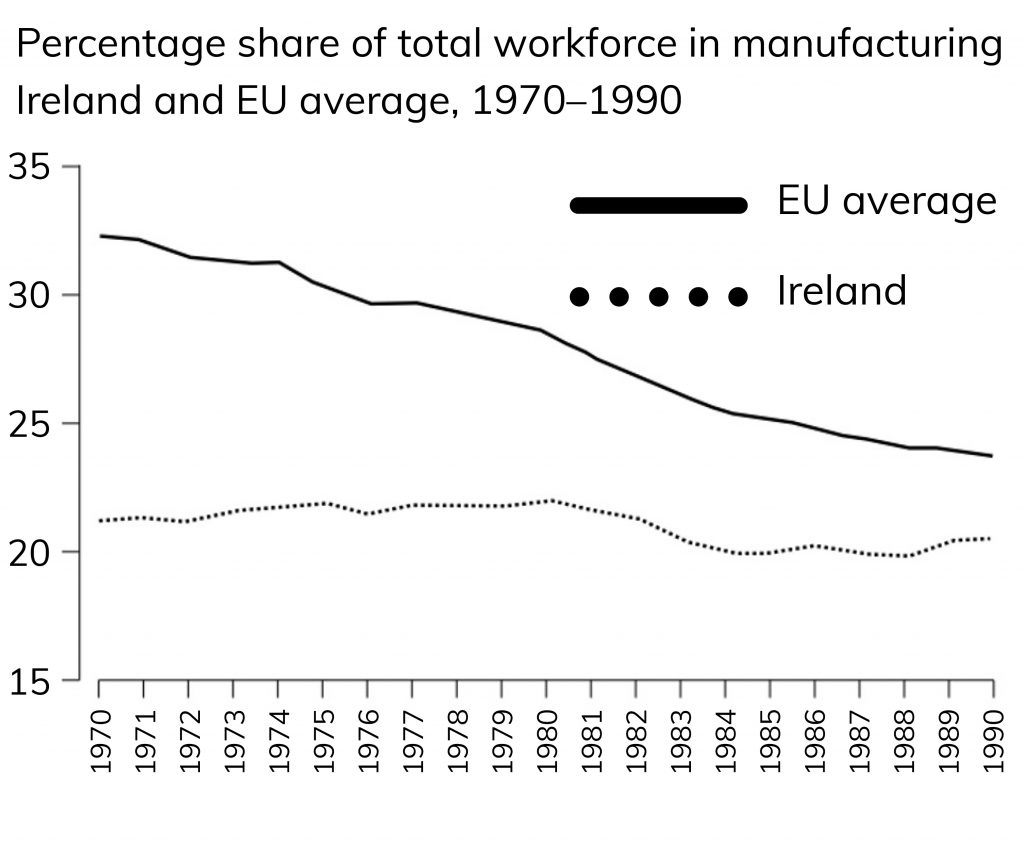

While the Irish indigenous sector followed EU-wide trends of manufacturing job losses, it did not enormously offset the positive contributions made to the sector by foreign-owned firms, where employment increased dramatically.

Between 1975 and 1995 manufacturing employment in Ireland overall decreased by only 3% compared to a European average of 20%. Higher technology use associated with FDI-generated production requires labour with relatively higher skill levels. Thus, foreign-dominated sectors, like Ireland’s manufacturing sector, employ substantially higher proportions of skilled labour than manufacturing industry on average – and with higher skill levels, labour is more difficult to outsource.

So, Ireland’s industrial and manufacturing sector today is, compared to other European states, disproportionately generated by FDI, and requires a more highly skilled labour force.

Simply put, Ireland has not experienced a dislocation of its manufacturing and industrial labour as a result of increased globalisation to the degree that it has occurred elsewhere.

Ireland has not experienced a dislocation of its manufacturing and industrial labour as a result of increased globalisation to the degree that it has occurred elsewhere

But then who does an Irish male, blue-collar worker without a university education vote for? Mostly Sinn Féin, a party vocally in support of minority and immigrant rights.

General election exit poll data has shown that this cohort is not necessarily less anti-immigrant than their continental counterparts. Sinn Féin is deemed a ‘tolerant party with intolerant supporters.’

Although anti-immigrant and anti-globalisation sentiment surely exists in Ireland, it has not been weaponised by the radical right because it does not exist in tandem with the ‘economic dislocation’ associated with a declining manufacturing sector.

Among the ‘losers’ of globalisation theory, Ireland presents itself as a theory-confirming, negative case: a Western democracy that did not have a declining manufacturing base where the populist radical right has been unsuccessful.

The Irish case, then, suggests that radical right populism may be rooted less within the cyclical ‘boom and bust’ of recession than in structural inequalities present in late-stage capitalism.

But this is not to suggest that Ireland has succeeded where other European states have missed the mark. Whether Ireland’s industrial policy and reliance on FDI has been an unqualified success is an altogether different question.