Political parties often adjust their strategies to address emerging issues, such as climate change and migration, in the hope of broadening their support or regaining voters lost in previous elections. However, warns Fabian Habersack, such changes in policy focus carry significant risks, especially if parties misjudge their electoral potential

The notion of voter availability offers a compelling explanation for why this is the case. When voters are ‘available’ on the market, parties have stronger incentives to innovate and adapt their strategies. Conversely, when new voters are entrenched and hard to reach, parties that open up to new policy issues risk alienating their base without securing replacements.

Examples abound. Consider Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) during the 2021 federal election. Seeking to broaden its appeal and counter the Greens, which had emerged as a serious contender for the Chancellery in the post-Merkel era, the SPD branded Olaf Scholz a Klimakanzler (climate Chancellor), preoccupied with environmental concerns rather than focusing exclusively on the party's traditional issue of social justice.

Meanwhile, with snap elections on the horizon, the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) are taking a different path, adopting increasingly restrictive stances on immigration and signalling a far-reaching realignment aimed at regaining 'well-meaning' voters lost to Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

However, in contrast with Green voters, research indicates that AfD supporters have become largely immune to mainstream mobilisation. Instead, they are locked into an ideological niche; one which AfD itself has actively cultivated over the past decade. Large numbers of the party’s supporters are thus ‘unavailable’ on the electoral market, rendering futile any attempt to regain their trust.

When shaping campaign strategy, how accurately do parties balance opportunities to attract new voters against the risk of losing their existing base?

This raises a crucial question: do political parties perceive their voter potential correctly and design their campaigns accordingly? In theory, the widespread use of data-driven campaigning and parties’ constituency ties should give them a clear understanding of where their voters stand. Yet how accurately do parties assess their opportunities to attract new voters — the ‘carrot’ in party competition — against the risk of undermining the loyalty of their existing base — the ‘stick’ — when shaping their campaign strategies?

Empirical evidence shows that parties’ willingness to broaden their issue focus depends on how they navigate this trade-off. When parties perceive significant potential to attract new voters and feel confident in the loyalty of their core supporters, they are more likely to diversify their policy offering. This pattern emerges from my investigation of campaign strategies in 162 parliamentary elections across 31 European countries, published in the European Journal of Political Research. Using a combined dataset of voter preferences (CSES and EES) and parties’ policy priorities (MARPOR), my analysis demonstrates how the combination of these factors — the ‘carrot’ of potential electoral gains and the ‘stick’ of potential voter defection — shapes how parties craft their campaigns.

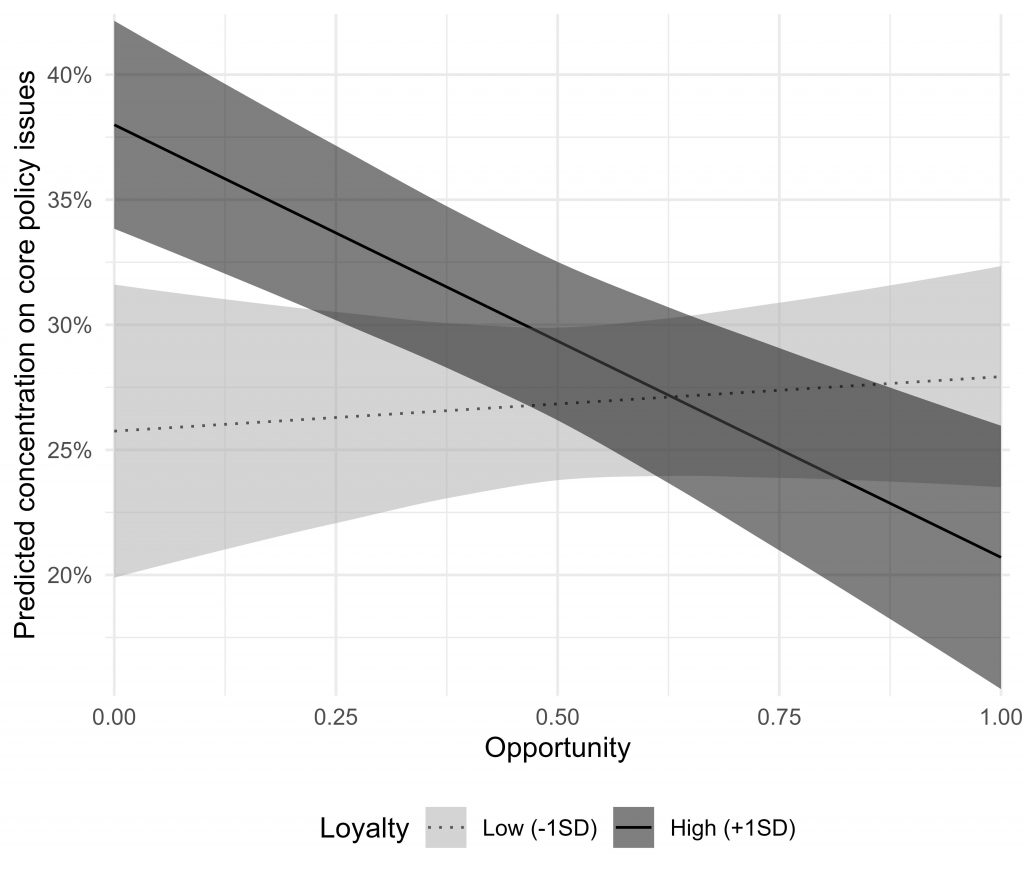

The figure below illustrates the interaction between electoral opportunity and voter loyalty. It shows how parties are most inclined to engage with peripheral issues when both factors are favourable. Parties tend to approach potential new voters more willingly when the risk of alienating previous ones is comparatively low (light grey). Conversely, where parties enjoy few opportunities to tap new market segments, stronger voter loyalty leads to an increased emphasis on core issues (dark grey).

France offers a more complex but equally illustrative example. Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance (RE) party initially positioned itself as a centrist alternative, appealing to a broad coalition of progressives and conservatives. Over time, however, his economic reforms and governance style alienated much of his progressive base, burning bridges with the left. Additionally, Macron began to adopt rhetoric and policies traditionally associated with the right, particularly on law-and-order issues. This was a strategic pivot intended to appeal to conservative voters amid a fragmented party system.

Macron’s strategy to broaden his appeal fractured his coalition amid France’s political and economic turmoil, strengthening Le Pen’s agenda and leaving space for her party to position itself as the country’s ‘true opposition’

While this shift addressed immediate electoral pressures, it alienated segments of Macron’s voter base. Concurrently, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) was pursuing a long-term strategy of normalisation. Le Pen aimed to present herself and her party as a legitimate mainstream contender. In combination, this has increased voter availability to the far right. Rassemblement National increasingly appears as the ‘true opposition’ and a credible alternative to Renaissance, particularly on issues like immigration and economic justice.

The case illustrates the risks of misjudging electoral potential. Macron’s strategy may have widened his appeal in the short term. However — in conjunction with France’s deepening economic and political crisis — it also fractured his coalition, inadvertently strengthening Le Pen’s agenda. This reflects longer-term European trends, where attempts to expand a party’s support base through broad appeal strategies often risk either diluting its ideological identity to the point of unrecognisability or triggering voter defections when core constituencies are abandoned. Thus, while such strategies may promise short-term gains, the forces they unleash often prove difficult to control in the long run. Their effect is to legitimise political contenders and destabilise traditional voter allegiances.

My findings have important implications for democratic representation. Staying the course helps parties consolidate support but ultimately risks them becoming irrelevant over time. Conversely, chasing new voters while misjudging their availability can destabilise parties’ ideological foundations. This leads to disillusionment among supporters, which in turn weakens democratic institutions amid an urgent crisis of representation.

The dilemma is compounded by the fact that parties’ strategies are often locked in place. Long-established routines, entrenched positions, and risk aversion make significant shifts rare and difficult. Fundamental change usually requires external shocks — such as electoral defeat — or leadership transitions. Yet, waiting for these disruptions comes at a cost, because it permits challengers to fill the void when established politics appears stagnant.

When established politics appears stagnant, challengers are quick to position themselves as dynamic alternatives

In an era of rising populism, political fragmentation, and shifting issue priorities, parties can no longer afford to play it safe. To remain relevant, they must engage with evolving voter concerns while preserving their ideological identity. This demands more than passive responsiveness to the electoral market. It requires willingness to innovate.

As Catherine de Vries and Sarah Hobolt argue, political entrepreneurs do not merely ‘react’ to evolving voter preferences; they craft campaigns that ‘create’ demand. Populist parties have demonstrated particular skill in this regard, carving out their niche and reshaping the political agenda. While established parties should not mimic their methods, it shows that voter availability is not static but fundamentally fluid and malleable.

To remain competitive, parties must reclaim their role as agenda-setters, while being mindful of the constraints imposed on them by the voter market. Failing to do so not only risks voter alienation, but threatens to leave certain groups absent from political representation. These are gaps that political challengers will be quick to exploit.