Andreas Dür and Robert A. Huber argue that (changes in) trade flows and regions’ economic structures matter for political outcomes. Regions’ trade competitiveness affects both legislators’ trade attitudes and incumbents’ chances of re-election

Trade has played an important role in recent political events. The rapid increase in imports from China into developed countries in the 2000s came to be known as China shock. It contributed to Trump’s surprise electoral win in 2016, the polarisation of US politics, Brexit, the rise of economic nationalism in Western Europe, populism, and the US-China trade war.

But the shock that resulted from China’s entry into the World Trade Organization should have been most pronounced in the first decade of the 2000s. Since that time, Western economies have adjusted to competition from China. We cannot use this shock, therefore, to help us understand more recent political developments.

So-called 'China shock' contributed to Trump’s win in 2016, the polarisation of US politics, Brexit, the rise of economic nationalism, populism, and the US-China trade war

On a global level, the impact of China far exceeds the impact of any other changes in trade flows. Yet individual countries or regions within countries can still experience trade shocks unrelated to China. For example, entry into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) mattered strongly for the trade flows of some states in the US. Finally, while China shock refers to an effect on imports, declines or increases in exports, too, may have political influence.

In recent research with Yannick Stiller, we began to advance our understanding of how trade affects politics. For this purpose, we created a new dataset capturing subnational trade competitiveness. Our aim was to gauge the ability of firms from a particular region to export their goods or services and to withstand import competition. To measure this concept, we used trade data to establish countries’ revealed comparative advantage (RCA) at the level of specific industries. We then combined the RCA with employment data from household and labour force surveys to establish to what extent a region’s economy produces goods and services for which the country has a comparative advantage. In other words, our data capture a region’s alignment with the country’s comparative advantage.

The resulting dataset includes data on subnational trade competitiveness for 6,475 regions in 63 countries across all continents over 21 years, 1999–2019. Our recent paper provides a detailed description of the dataset and extensive validation.

In two recent publications, we show that subnational trade competitiveness as measured in our dataset – and hence the combination of (changes in) trade flows and employment structures – matters for political outcomes.

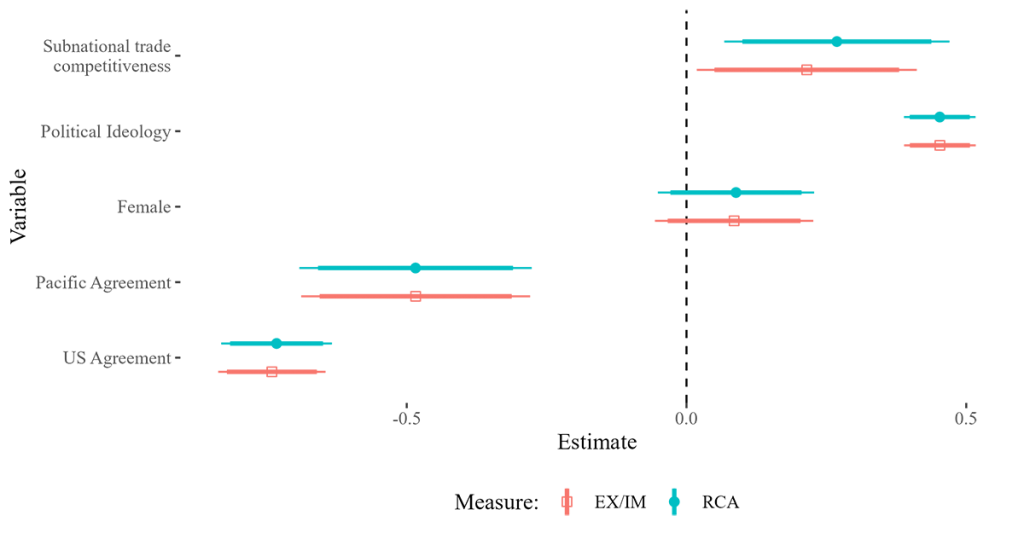

The first study explains Latin American legislators’ attitudes toward trade agreements. We expected that legislators representing constituencies with low trade competitiveness would be less supportive of trade agreements than legislators representing districts with a high degree of trade competitiveness. Survey data with over 3,500 legislators from 16 Latin American countries allowed us to test this expectation. The findings offer support for our argument, showing that trade competitiveness does indeed matter for legislators.

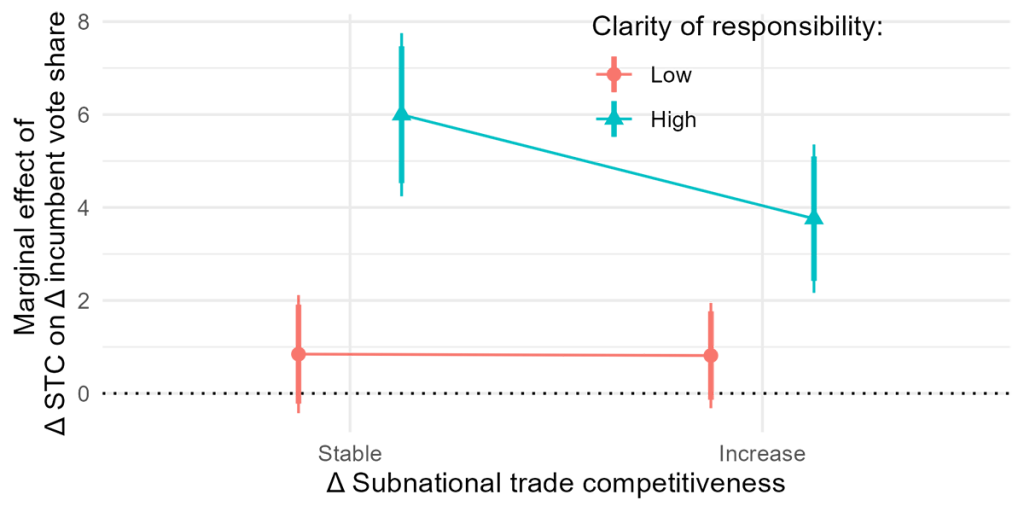

In a second study in the European Journal of Political Research, we shifted the focus from legislators to voters. Our research asked how changes in subnational trade competitiveness affect voters’ electoral choices. Indeed, some evidence suggests that in the 2016 US presidential elections, voters in regions losing international economic competitiveness turned away from the incumbent party and allowed Donald Trump to win the presidency.

If voters penalise incumbents for a decline in trade competitiveness, incumbents must weigh carefully the impact of trade policy decisions

To study this question across more countries and elections, we relied on data from 29 democracies worldwide, dating from 2000 onwards. Our findings indicate that a decline in competitiveness harms incumbents’ electoral prospects. Stable or improving conditions, on the other hand, lead to lesser losses. Notably, a decrease in subnational trade competitiveness leads to a 6.9 percentage point drop in incumbents’ vote share. This highlights the potential electoral cost of changing trade flows. This finding also supports the results from our study on legislators’ trade attitudes: if voters penalise incumbents for a decline in trade competitiveness, it makes sense for them to weigh carefully the impact of trade policy decisions on voters.

Both studies attest to the important role played by contextual factors. For one, we find that the effect of (changes in) subnational trade competitiveness is contingent on the political incentives induced by the political context. Legislators are more attentive to subnational trade competitiveness in districts with smaller magnitude. Equally, we find that incumbents are more likely to be affected by changes in subnational trade competitiveness if voters find it easy to identify who to hold accountable. Hence, the political opportunity structure is a core moderating factor.

Incumbents are more likely to be affected by changes in subnational trade competitiveness if voters find it easy to identify who to hold accountable

Moreover, both studies provide evidence for the importance of political ideology. The first shows that left-wing legislators pay more attention to the subnational trade competitiveness of the districts they represent. The second reveals that the effect of changes in subnational trade competitiveness is largest for centrist politicians or parties. What may seem like a contradiction has an intuitive explanation: those in the centre are ideologically least committed to either free trade or protectionism. Voters may therefore expect centrists to be most responsive to constituency demands. Indeed, voters punish centrists most severely if subnational trade competitiveness declines.

The political fallout of voters’ dissatisfaction resulting from declining competitiveness can extend beyond losses for political incumbents. On the one hand, it can precipitate a protectionist backlash. And this, in turn, can have adverse effects on countries’ economic growth. On the other hand, in the longer run this dissatisfaction may erode social cohesion. It can breed broader discontent with how democracy works, meaning that support for the political system itself is undermined.

Our research underscores the importance of taking the distributional effects of trade seriously. Policymakers should design trade policies in a way that either reduces losses or compensates losers. These implications are particularly important at a time when governments increasingly leverage trade policy for geopolitical goals. If governments fail to mitigate these measures’ distributional impact, public support for broader governmental goals is likely to erode.