We used to believe that autocratic educational policies stifled free thought. However, as Russia's meritocratic policy (supporting talented youth) shows, state-created incentives can serve to spread 'dissident' ideas that differ from those championed in national exams. A significant portion of schoolchildren, writes Victoria Portnaya, may absorb these ideas while preparing for state-sponsored intellectual competitions

In 2020, President Vladimir Putin proposed revisions to Russia's federal statute On Education, which came into effect in September of that year. Putin's objective was to broaden the definition of education. He aimed to include the cultivation of 'a sense of patriotism and citizenship, as well as respect for the memory of the fatherland's defenders'.

Russians live under a rigid autocratic regime in which education is, by definition, controlled almost entirely by the state. Nonetheless, Russia enacts policies which may, unbeknown to the Kremlin, actively encourage free thinking and liberal-democratic enlightenment among the young. This paradox is a distinguishing feature of Russia's meritocratic approach to helping outstanding and gifted students.

Russia's educational Olympiad is an intellectual competition among university applicants that offers the chance to be admitted to a university without having sat the entrance exams. According to Article 71 of Russia's Federal Law On Education, winners of All-Russian Olympiads win either a state scholarship or a significant discount on tuition.

The winners of the final stage in Moscow receive grants of ₽500,000 roubles (around $5,500). Students' Olympiad triumphs are thus one of the primary metrics in assessing a school's ranking and instructor performance. Olympiads have a direct impact on school subsidies, on grants, and on teachers' pay.

Olympiad results have a direct impact on school subsidies, on grants, and on teachers' pay

The allure of material benefits and funded university places gives students a strong incentive to prepare for Olympiads. Teachers 'send' their students to Olympiads to improve their success rate and, thus, salary. Schools encourage students to participate in order to improve the schools' ranking, and to gain extra funding.

It's unsurprising, then, that a whopping 240,000 students sat stage one of the first-level Olympiad Higher Sample in the 2022/23 academic year – more than 48% of the entire year's graduates! Interestingly, one of the most popular Olympiad disciplines is social studies, which allows students to pursue a wide range of specialities.

A niche market of public schools and courses has grown up around Olympiad preparation. These schools exist alongside the Moscow Department of Education's Centre of Pedagogical Excellence (CPE). Partner schools in Moscow offer Olympiad courses in specialised disciplines, so students from different regions can practice alongside the Moscow team. The Olympiad website offers revision tips, CPE courses, and access to school groups on social media.

Recent webinars in one of the most popular private preparation courses include titles such as Why is Russia backward? and Totalitarianism through the eyes of the average person. Topics on the intensive course timetable include What is democracy? and What is ideology? On the list of recommended preparatory readings are Almond and Verba's Civic Culture and Stable Democracy, Dahl's On Democracy, Ajemoglu and Robinson's Why States Fail, Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and a number of other similarly oriented books.

Such course designs and study topics are a far cry from Putin's 'patriotic' education and the narrative pushed in Medinsky's modified history textbook. Putin would have these children absorbing imperial narratives, hatred of all things Western, and following 'Russia's special path'. Instead, incentivised to cram for Olympiads, children are studying democratic ideas, and recognising Russia's economic and political backwardness as a fact. They learn that 'democratic, inclusive institutions are useful for economic growth, while extractive institutions are not'.

Incentivised to cram for Olympiads, children are studying democratic ideas, and recognising Russia's economic and political backwardness as a fact

It turns out that the brightest students – and those most likely to join the ranks of Russia's elites – are getting a liberal-democratic civic education. Joint Olympiad preparation, in schools and study centres, thus creates groups of connected people with a distinct identity.

In other words, through meritocratic policies, the state creates a group of young people acutely aware of the regime's authoritarianism. These people are politically enlightened, and potentially supportive of liberal ideas. They are closely connected by social ties, common values, and ideas – all useful qualities for collective action against the regime. In general, they represent a liberal enclave of politically enlightened, and thus 'harmful' dissidents.

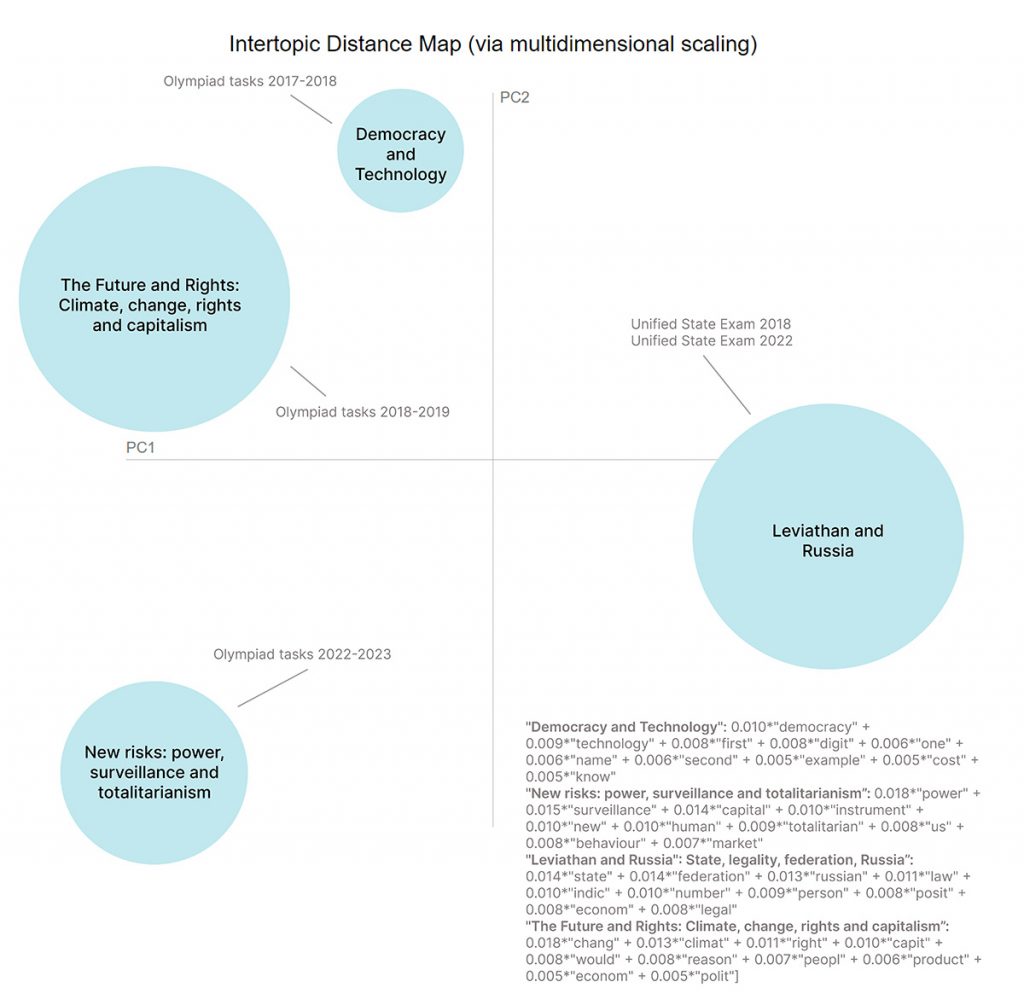

I examined texts of Olympiad problems for 2017–2018, 2018–2019, and 2022–2023. I compared these with the demonstration version of the 2018 USE (national exams) sample, and the modified 2022 version, using topic modelling methods (Latent Dirichlet Allocation). My aim was to discover whether ideas in the Olympiad problems differed from the ideas in the state exams.

The Russian state is inadvertently producing and supporting an enclave of dissidents

The texts discussed four themes, the third of which, Leviathan and Russia, characterises both USE demonstration variations. This reflects state-centricity, legalism, and Russia. The 2017–2018 Olympiad tasks are Democracy and Technology, the 2018–2019 and 2021–2022 tasks The Future and Rights, including topics about capitalism, climate change, and rights. 2022–2023 Olympiad tasks raise the second theme of new risks of totalitarianism, control, increasing power over people, and constant surveillance (which we can attribute, among other things, to the increased repressiveness of the regime after the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine).

My analysis shows how social studies Olympiad topics differ from those in national exams, which are characterised more by state-centrism, as Russian educational policy goals imply. This suggests that the Russian state may be inadvertently producing, and supporting, an enclave of dissidents. Through meritocratic policies, it offers a liberal education to its country's most gifted children, and consolidates this within the Olympiad community.

With the Olympiad curriculum, the Russian state is thus putting itself at risk. It is evidence that even inside a repressive, anti-liberal, authoritarian regime, liberal zones can arise unintentionally. These 'spaces' have the potential to act as a lever for democratic transformation.