In representative democracies, many citizens feel disconnected from those who make political decisions on their behalf. In extreme cases, they may even refuse to accept democratic decisions and contemplate alternative forms of government. Lisa van Dijk, Jamie Pow and Sofie Marien test the effectiveness of ‘minipublics’ to offset these problems

The proper functioning of representative democracy rests on a relationship between elected representatives and the citizens they represent. Yet many citizens perceive a gap between politicians and themselves. An increasingly popular method of closing this gap has been to engage ordinary citizens directly in political decision-making.

Democratic innovations such as deliberative minipublics bring together a small number of citizens, selected at random, to discuss and advise on political issues. Countries around the world have used them to address complex and / or contested themes. In Canada, they have been used to debate electoral reform; in the UK and France, to discuss climate change policy.

However, only a small number of people can take part in a minipublic – usually only a hundred or so. This means that most members of the wider public must watch from a distance. The question therefore arises: would the wider public trust these other citizens to make policy recommendations on its behalf? If so, why?

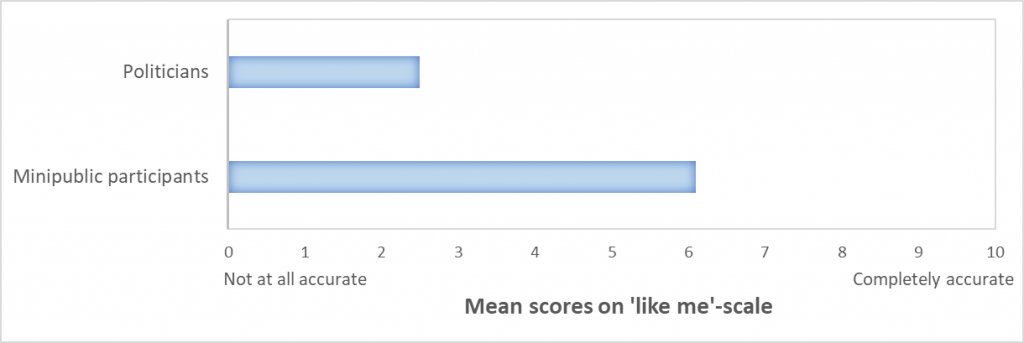

Our recent article in the Journal of Deliberative Democracy draws on original survey evidence. Findings indicate that many citizens see participants in minipublics as ‘people like them’ – and to a much greater extent than they see politicians as being like them. It seems that the wider public perceives participants in minipublics, but not politicians, as sharing their experiences and their background:

It's an important point because it highlights a key limitation of the electoral process. This is that elections don't necessarily result in voters being represented by people they regard as similar to themselves.

Our findings reveal potential for a stronger psychological connection to develop between citizens and minipublic participants. This despite the fact that the latter are selected randomly rather than elected.

many citizens see minipublic participants as ‘people like them’ – to a much greater extent than they identify with politicians

Crucially, we find that the more citizens perceive minipublic participants to be like them, and the more they perceive politicians to be unlike them, the more they are supportive of deliberative minipublics.

What does it mean for people to perceive minipublic participants to be ‘like them’? Do citizens only want people who share their personal characteristics to take part? Or do they also value diverse perspectives and rationales?

Zooming in on the specificities of our study, we observe that citizens prioritise the inclusion of participants who share the characteristic most directly relevant to the issue at stake.

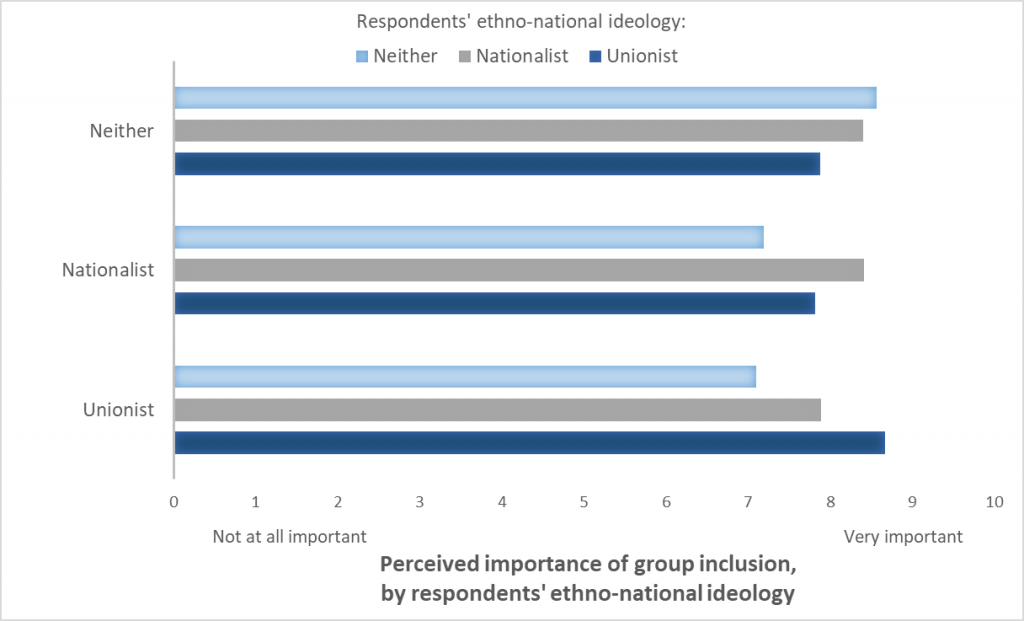

Our research focuses on a deliberative minipublic in Northern Ireland. Its purpose was to consider whether the polity should remain within the UK, or leave and join a united Ireland. We can associate this issue with ethno-national ideology; that is, whether citizens see themselves as (British) unionist, (Irish) nationalist or neither.

What we see is that unionist respondents consider the inclusion of unionist participants in the minipublic more important. Nationalist respondents, on the other hand, place more importance on including nationalist participants:

Despite these differences, our research indicates that citizens don't focus solely on the presence of citizens ‘like them’ in the deliberative minipublic. Even respondents who have a nationalist background find it important that unionist participants are present at the table. Equally, respondents with a unionist background attach importance to the presence of nationalist participants.

In a deliberative minipublic, citizens don't focus solely on the presence of citizens ‘like them’

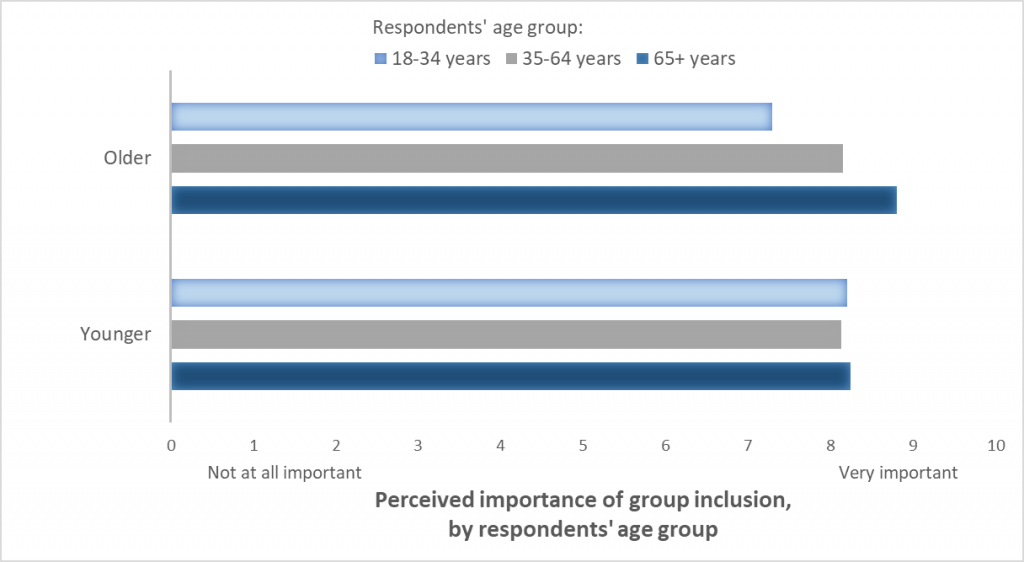

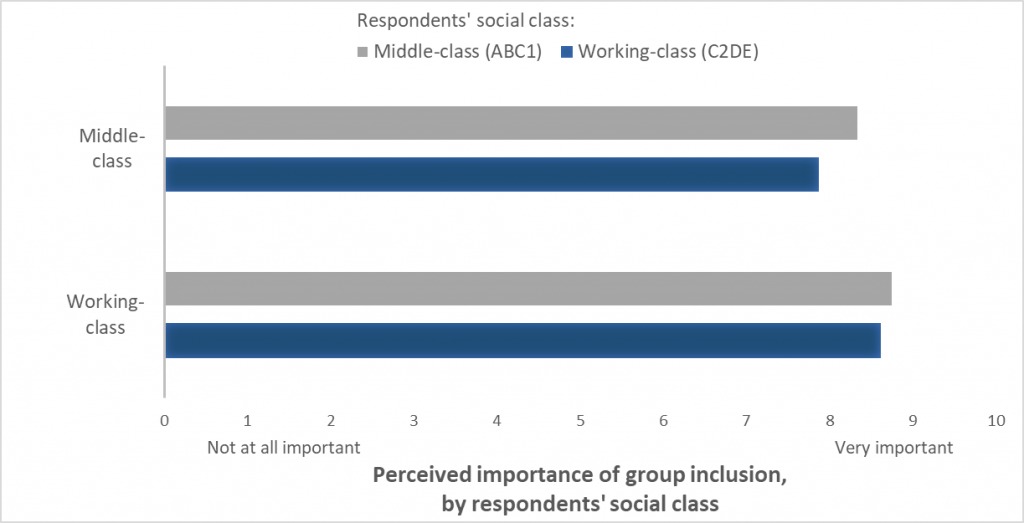

Moreover, the trait most salient to the issue being considered by the minipublic is not the only characteristic that matters. For example, older respondents attach greater importance to the inclusion of older people in the minipublic than younger respondents. Middle-class respondents attach greater importance to the inclusion of middle-class people than working-class respondents.

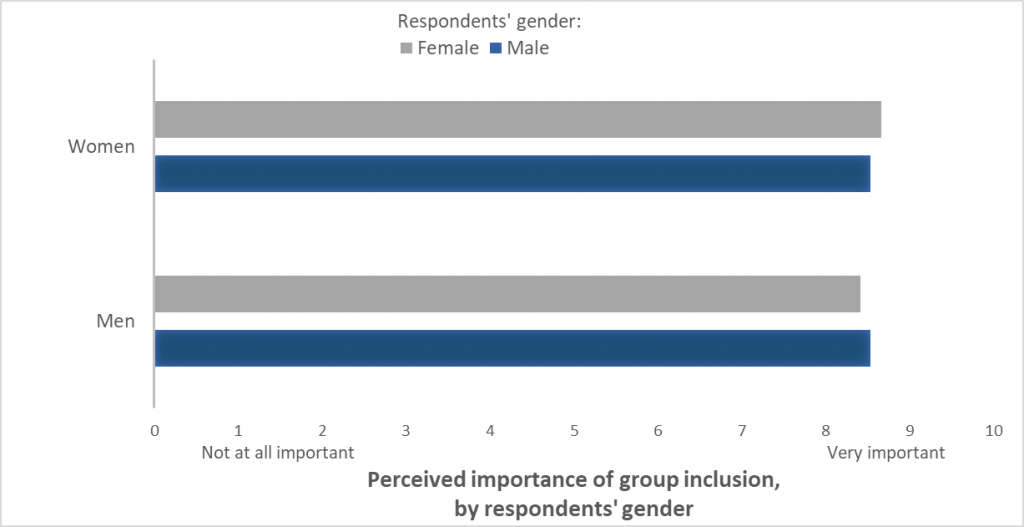

Yet, again, we find that citizens would like a wide diversity of people to be included in deliberative minipublics. Overall, they consider it important that men and women, young and old, working- and middle-class are present at the table:

Does this mean that citizens want just anybody to be included? In short, no. Our survey asked people how important they felt it was for politicians to be included in the minipublic. The answers revealed striking differences.

Our findings indicate that citizens are much less enthusiastic about politicians taking part in deliberative minipublics. This is especially the case when we compare it to the importance people attach to the inclusion of different groups in society.

What do these findings imply about the role of deliberative minipublics in contemporary politics? Following prominent academics in the field, we can see deliberative minipublics as a different type of political representation.

It's a representation not based on elections, which allow citizens to select and sanction politicians who serve multiple-year mandates. Instead, it's based on a psychological attachment between citizens and randomly selected participants set specific, limited tasks.

Through the structured and informed consideration of specific policy issues by diverse groups of ordinary citizens, minipublics can enhance the democratic process. Minipublics can inject citizens’ perspectives and practical know-how into political decision-making. Rather than challenging the authority of conventional actors and institutions, we can understand minipublics as complementary to the technical expertise and bureaucratic resources available to elected politicians.

minipublics complement rather than challenge the technical expertise and bureaucratic resources available to elected politicians

The wider public cannot be directly involved in these initiatives. Nor can the public exercise control over the minipublic or its outcomes in the same way that they grant authority to politicians or hold them accountable.

But many people don't see this as a problem. When citizens outside the minipublic perceive participants inside the forum as ‘people like them’, it evokes support for the minipublic, and for its outcomes.

This blog is based on the authors' Journal of Deliberative Democracy article It’s Not Just the Taking Part that Counts: ‘Like Me’ Perceptions Connect the Wider Public to Minipublics