Declining public trust in political institutions raises concerns that citizens may turn away from democratic forms of decision-making. Recent cases of democratic backsliding seem to confirm this fear. Yet, as Ben Seyd argues, there is little evidence that declining trust impels citizens to embrace autocratic forms of decision-making

Democracy is eroding across the world, while authoritarian leaders have enjoyed notable successes at recent elections. At the same time, public trust in representative institutions is declining. Against this backdrop, some analysts argue that growing distrust in political rulers is undermining public support for democratic principles and practices. Might democracy slowly be eroding internally?

There are good reasons to doubt this. For a start, there is little evidence of waning public commitment to democracy. If anything, it appears to have strengthened across the globe in recent years. Authoritarian leaders are winning elections despite, not because of, levels of popular support for democratic principles and practices.

Low political trust is perfectly compatible with high and enduring rates of popular support for democratic arrangements

In addition, as previous analyses have pointed out, low political trust is perfectly compatible with high and enduring rates of popular support for democratic arrangements. Indeed, a recent study showed that declining trust among individuals is associated with lower, not higher, support for authoritarian rule. Another study found declining trust to have no effect on popular support for authoritarian leadership. Instead, it found greater support for direct citizen involvement in decision-making.

Reassuringly, then, the evidence suggests declining trust might not erode public commitment to democratic norms. But existing studies have examined the effects of declining trust over only a few years, which is a relatively short period of time. What about a situation where trust erodes over a longer period? Does this more sustained build-up of discontent tip individuals into the embrace of non-democratic arrangements?

Evidence suggests declining trust might not erode public commitment to democratic norms over a few years – but does a sustained build-up of discontent tip individuals into the embrace of non-democratic arrangements?

To address this question, I focus on Britain, where levels of trust recently hit a record low. I study the effects of declining trust by using panel surveys fielded by the British Election Study (BES) across an eight-year period, from 2016 to 2024. These surveys enable us to track the effects of changes in trust among the same individuals over a long period of time.

To gauge people’s views towards alternative democratic arrangements, I use measures tapping support for authoritarian rule and direct democracy. The former is measured through a survey question that asks about support for a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament or elections. The latter is measured through a combination of two survey questions that ask whether the people, not politicians, should make policy decisions, and whether the respondent would prefer citizens rather than politicians to represent them. Alongside these barometers of people’s support for alternative democratic arrangements, the surveys measure people’s trust in Members of Parliament.

These questions were asked of BES respondents across five panel waves between autumn 2016 and summer 2024. Although panel surveys usually suffer from response attrition, the large BES samples meant that we have at least 2,000 panel respondents across the eight-year period.

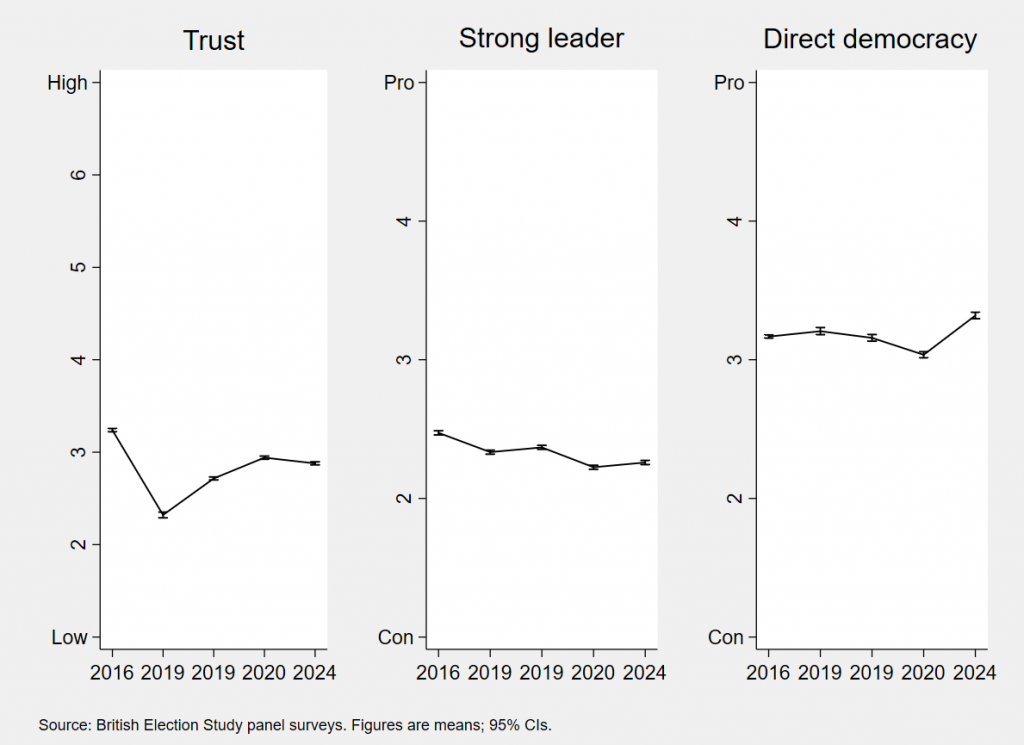

To give a flavour of the shifts in British people’s attitudes over the period, the graphs below show changes in trust and support for strong leaders and direct democracy. Over the period, levels of political trust among British citizens declined, falling particularly sharply after Brexit in 2016. Public support for strong leaders also declined slightly, while there was a slight increase in support for direct democracy.

We can identify the effect of declining rates of trust on support for strong leaders and direct democracy through models that parcel out, or control for, characteristics of individuals that do not change over time. These fixed-effects models allow us to identify more precisely the effects of factors – like trust – that do change over time.

The models I use also include factors that might relate to people’s trust and to their support for different democratic arrangements. In particular, I measure people’s economic optimism (whether they see the economy as getting worse or better) and authoritarian tendencies (their responses to statements like ‘Schools should teach children to obey authority’).

Declining trust helps stimulate support for autocrats, but the effect is relatively small. Lower trust has a greater effect in driving support for more people power

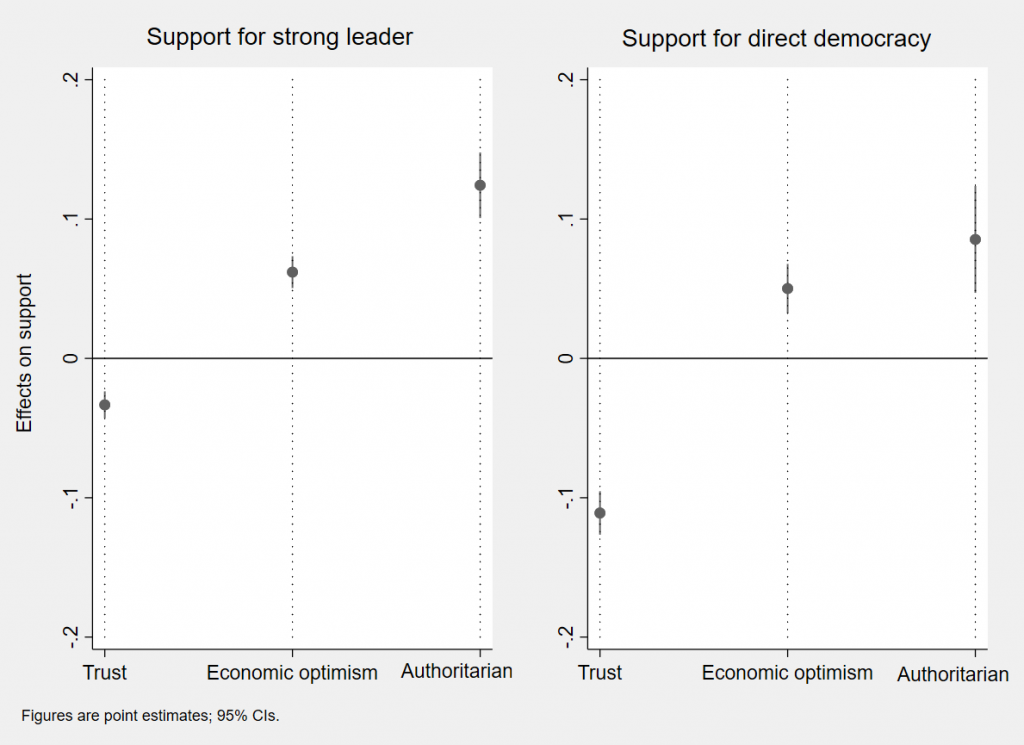

The graphs below show how changes in trust, economic optimism, and authoritarian tendencies influence support for strong leaders and direct democracy. They reveal that increases in trust are negatively associated with support for a strong leader. Put differently, declining trust helps stimulate support for autocratic rulers. However, the effect of trust is relatively small. The coefficient sits close to the 0 line (no effect) and has substantially less effect on people’s support for a strong leader than changes in economic optimism and authoritarian feelings.

Somewhat surprisingly, economic optimism is positively, not negatively, associated with support for a strong leader. As people become more optimistic about the economy, they seem more inclined to support a strong leader. Hence popular support for autocratic arrangements does not appear to reflect people’s economic frustrations. But nor does it arise substantially from their declining trust.

In fact, as the right-hand graph shows, declining trust has a more significant effect on people’s support for direct democracy. As trust increases, there is a marked decline in support for direct democracy. Hence, as people lose trust in politicians, they become substantially more likely to favour greater people power.

The evidence from Britain suggests that even long-term deteriorations in political trust may not significantly corrode citizens’ democratic commitments. While citizens in many countries are losing trust in political actors and institutions, this does not necessarily lead to an erosion of democracy ‘from within’. If anything, declining trust is more strongly associated with public demands for greater popular voice in political decision-making.