In recent years, demonstrations against measures to contain the spread of Covid-19 have dominated the protest landscape. Sophia Hunger, Swen Hutter and Eylem Kanol explain what drives individuals from passive sympathy to active participation. They find that political and ideological attitudes, rather than 'biographical availability', play a critical role

Since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, many different groups in states around the world have been galvanised to protest against the containment strategies implemented by their governments. This phenomenon was particularly pronounced in Germany, where anti-containment demonstrations have become emblematic of a broader societal conflict. Thus, the German case serves as an illustrative example for investigating the mobilising potential of anti-containment protests.

How much do sympathisers with these protests, and the people involved in them, have in common? What motivates a person to shift from merely sympathising with a cause to being an active participant in it?

The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic triggered a variety of political actions. These actions ranged from local neighbourhood aid to expressions of solidarity with healthcare workers to public demonstrations against government-imposed containment measures.

In Germany, public protests against Covid containment measures have become emblematic of a broader societal conflict

Germany enjoyed relative success in containing the spread of the virus. Yet anti-containment protests in the country quickly gained traction, and attracted a considerable following. Indeed, throughout 2020, the pandemic was at the root of almost half of all protests in Germany.

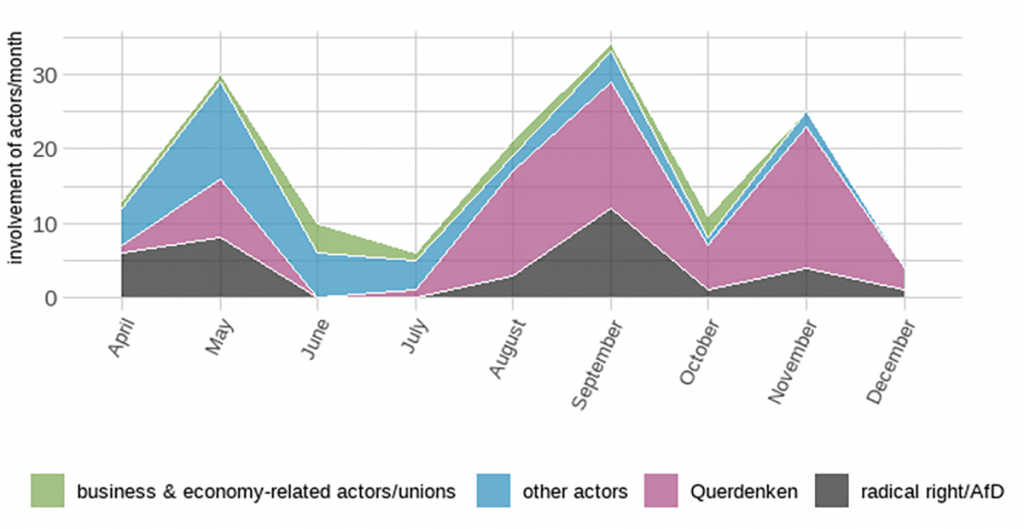

German protests related to Covid containment measures emerged in three waves. With the easing of the first lockdown, in April 2020, we recorded the first spike in protest activity. A broad range of actors, including artists, parents, and people in the hospitality industry, took to the streets.

The second wave of protest came several months later. This time, the picture was drastically different. Demonstrations grew in size, and began to coalesce around more homogenous demands. This second wave culminated in two events in Berlin in August 2020, each of which drew roughly 30,000 participants.

The 29 August protest witnessed a concerning development. A group of individuals bearing visible extreme-right symbols breached the security of the Bundestag, attempting to enter the building by force. This event marked a significant shift towards the participation of more radicalised actors in anti-containment protests. These actors included followers of the QAnon movement, the extreme right Reichsbürger, and the prominent Querdenker (lateral thinkers) movement.

During our observation period, anti-containment protests progressed toward increasingly confrontational forms of action and anti-system claims rejecting all measures aimed at containing the spread of Covid. Alongside these protests, racist and antisemitic conspiracy theories, and calls for the dissolution of the German government, proliferated.

To understand the emerging polarisation during the pandemic, our study analysed the issue-specific mobilisation potential of the anti-containment protests. We can understand this as an individual's proneness to engage in protests to advance their interests.

There is considerable difference between a movement's managing to convince people that their goals are worthwhile and mobilising them to get involved. We distinguish this, respectively, as consensus mobilisation and action mobilisation.

Moving beyond a narrow focus on electoral behaviour is particularly relevant during times when protest campaigns and social movements become key signifiers of conflict

The concept of ‘mobilisation potential’ is a useful lens through which to examine the characteristics of individuals drawn to anti-containment protests. Doing so reveals the underlying demand-side dynamics of collective action.

By centring an individual's propensity to act on behalf of their preferences, the mobilisation potential approach offers a more nuanced understanding of the micro-level factors contributing to a movement’s formation. It also allows us to move beyond a narrow focus on electoral behaviour. This seems particularly relevant during times when protest campaigns and social movements become key signifiers of conflicts.

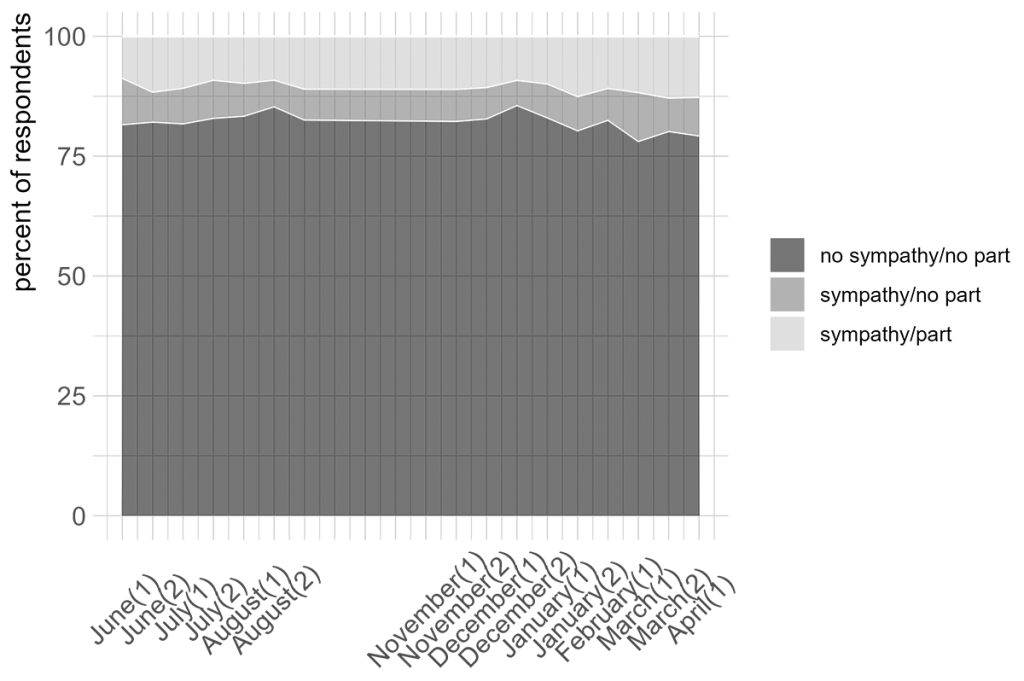

So, how significant is the anti-containment protests' mobilisation potential? It is safe to say that the Covid-19 protests had a considerable and stable mobilisation potential between June 2020 and April 2021. Nearly every fifth respondent among the roughly 13,000 participants in our survey expressed sympathy for the demonstrations. Moreover, 60% of sympathisers said they would be willing to take part in such a demonstration if given the chance.

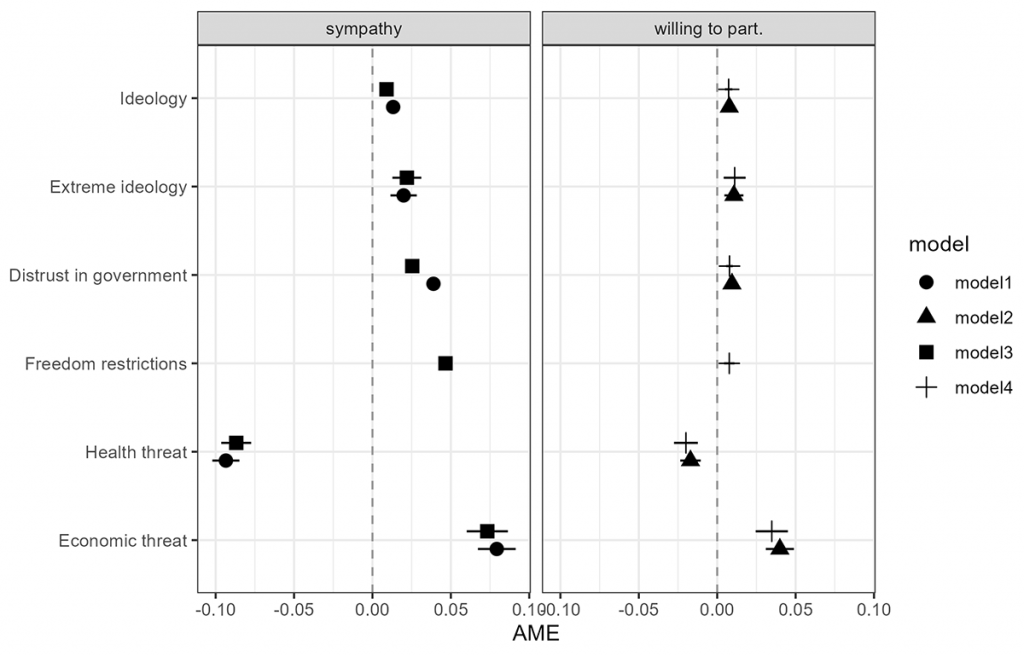

But which individuals are more likely to become sympathisers with the movement? A central aspect of the anti-containment protests are their anti-system claims. These claims are also reflected in the movement’s mobilisation potential. In particular, these protests tend to attract individuals who harbour a general sense of distrust toward the government. Such people are overrepresented among the ranks of the movement.

In addition, the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests is intertwined with broader left-right political conflicts, because individuals with extreme right-wing views are much more willing to protest. As the pandemic spread, a growing rift over restrictions on political freedom emerged. We call this the 'freedom divide'.

During the pandemic, the need to protect public health often conflicted with the desire to uphold individual freedoms and fundamental rights

During the pandemic, the need to protect public health often conflicted with the desire to uphold individual freedoms and fundamental rights. People who perceived their individual liberties to be threatened were more likely to express support for the protests.

Personal health considerations during the pandemic decreased an individual's inclination to support the anti-containment protests. Conversely, the perception of economic threats was positively associated with support for the movement.

The common explanation for the transition from passive sympathy to active participation in protest activities is ‘biographical availability’. This refers to an individual's relative lack of competing commitments or obligations. The biographical availability theory posits that the absence of time-consuming, costly commitments, such as employment or childcare responsibilities, increases the likelihood of an individual's involvement in protest behaviour.

However, anti-containment protests in Germany show how a combination of factors shape both steps of the mobilisation process – who sympathises with and who is likely to participate in the movement. These factors include ideological beliefs, political attitudes, and pandemic-related economic and health threats.

Earlier approaches emphasised the biographical constraints on individuals joining protest activity. Anti-containment protests, by contrast, highlight the important role political attitudes and ideological polarisation play in driving sympathisers to engage in the movement.

The authors would also like to thank Mika Bauer for her support in preparing this blog post

The lockdowns violated civil liberties, harmed the economy and social life, and achieved negligible (if any) health benefits.

The protestors were right.