Authoritarian states deliberately use a number of tools to manage their image internationally, writes Alexander Dukalskis. Creating positive news, distracting and silencing critique, and shaping elite opinion help make the world safer for dictatorships

In 2012 news broke about a public relations contract between a firm called Racepoint Global and the Rwandan government. The contract involved a plan written by the firm to improve Rwanda’s image internationally, including managing the image of its authoritarian leader, Paul Kagame.

The plan is telling. Of course, it includes the standard public relations stuff like making the country look attractive and Kagame a wise leader. But more interestingly, it details its aims to undermine Rwanda’s critics abroad – including human rights activists.

The plan also aims to cultivate journalists in leading outlets to promote a positive image of Kagame, and Rwanda. Thanks to the US Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), you can look up the plan for yourself.

We often think about states promoting a positive image of themselves abroad through 'soft power' initiatives. And rightfully so: they do this a lot. But the Rwanda Racepoint memo is a revealing reminder that states – and especially authoritarian ones with an image problem – do a lot of other things to manage their image. These activities are often ethically dubious or sometimes outright illegal – violent, even.

In his excellent book, journalist Ron Nixon details the methods South Africa’s Apartheid regime used to improve its dire image internationally. These included paying lobbyists, and sponsoring 'look and see' tours to South Africa for opinion-shapers. The regime even attempted to purchase a newspaper covertly, discrediting critics as closet communists. Many authoritarian states do all these things and more.

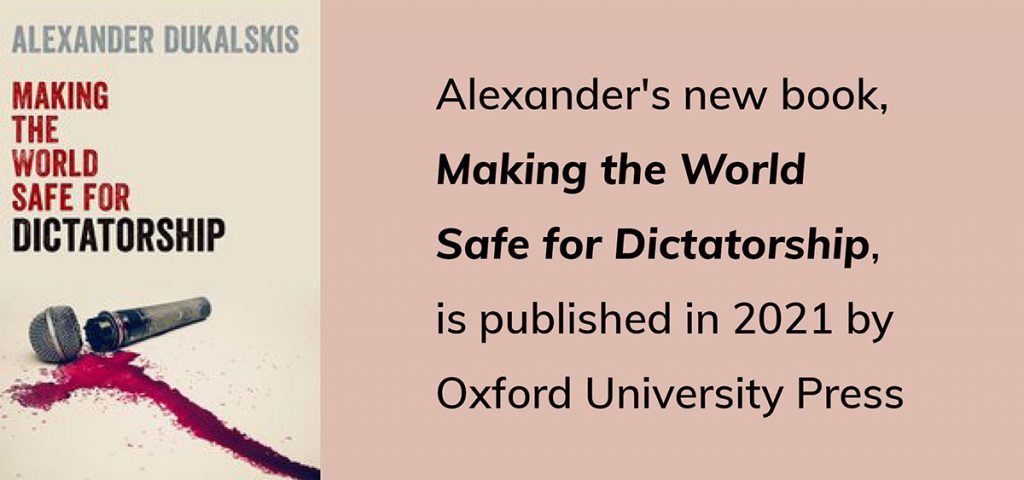

In my new book Making the World Safe for Dictatorship, I try to understand what motivates these efforts and how they operate. Focusing on authoritarian states, I create a framework of what I call 'authoritarian image management.'

Authoritarian states use a range of tactics abroad to burnish their image and stamp out criticism; in short, they try to make their world safe for their dictatorship

Authoritarian states use a range of tactics abroad to burnish their image and stamp out criticism; in short, they try to make their world safe for their dictatorship. The idea of the book is to put all these different methods into the same conversation. It aims to understand their strengths and weaknesses, and how different states adopt different tactics.

Authoritarian image management has two audiences: mass publics or specific elites. Further, it can have two main forms: promoting positive messages or obstructing criticisms of the state. Put together, you get four types of authoritarian image management, depending on audience and form.

To study these tactics, I use a range of data, including FARA documents, interviews, case study evidence, and video analysis. I also created a publicly available database of all instances in which authoritarian states threatened and/or repressed one of their own citizens abroad between 1991 and 2019.

Here let me highlight some examples that have transpired since the book came out.

First, perhaps the most salient example of an authoritarian state putting out positive messages designed for a mass audience is covid-related messaging by the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The Chinese authorities have attempted to present the PRC as successful at home in eliminating the disease and generous abroad in helping other countries meet the pandemic’s challenges.

In a recent paper with my co-author Sam Brazys, we analyse the messaging of Xinhua, China’s main state news agency, and find that it portrays China in positive and generous terms. The idea is to portray China’s authoritarian system as capable domestically and non-threatening internationally.

China’s Xinhua state news agency portrays the country's authoritarian system as capable domestically and non-threatening internationally

Second, authoritarian states don’t just try to present positive images to the general foreign public. They also try to mitigate or distract from bad news or criticism.

If one examines Russia’s main external TV station – RT – for news about the case of arrested dissident Alexei Navalny, this mode of authoritarian image management is apparent. He is variously portrayed as an extremist or terrorist (or at least terrorist-adjacent), a stooge of foreign powers destined to be defeated, and yet another example of how Russia is reasonable while 'the West' is anything but.

Someone like Navalny is a public relations problem for Russian authorities, and his global name recognition means that the government can’t just pretend he doesn’t exist. The authorities perceive that they have to respond to the negative press.

Third, authoritarian states can try to silence specific critics or groups of critics abroad. This tactic involves what scholars call 'extraterritorial repression' or 'transnational repression.' Freedom House has recently released a major report and underlying data on the subject.

A controversial and high-profile example is the case of Paul Rusesabagina, portrayed in the movie Hotel Rwanda as saving lives during Rwanda’s 1994 genocide.

From abroad he frequently criticised Kagame’s government. In August 2020 he was apparently deceived into boarding a charter flight and ultimately ended up in Rwanda where he now faces a terrorism trial.

A prominent critic of the Rwandan government is now no longer able to voice his criticisms to international audiences.

Authoritarian states try to cultivate elite opinion shapers to disseminate positive messages to international audiences. Sometimes this is through direct funding, sometimes through access. It may even stem from ideological affinity.

Authoritarian states try to cultivate elite opinion shapers to disseminate positive messages to international audiences

There are lots of potential examples here and many grey areas. One topic is funding for think tanks. In her recent report on the subject, Nadège Rolland details how authoritarian states try to fund think tanks to shape elite conversation on issues important to them. A similar logic can extend to universities.

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg. Authoritarian image management is about more than just 'soft power'.

Once you start thinking about the multiple methods available to authoritarian actors abroad it becomes important to see them as tools in a toolkit rather than as unrelated to one another.