Nelson Santos, Sofia Serra-Silva, and Tiago Silva analysed voting patterns in Portugal’s parliament. They found that the legislative behaviour of populist radical-right Chega contradicts the party’s anti-system rhetoric. Meanwhile, conflict has reached unprecedented levels in what was historically a more consensual parliament

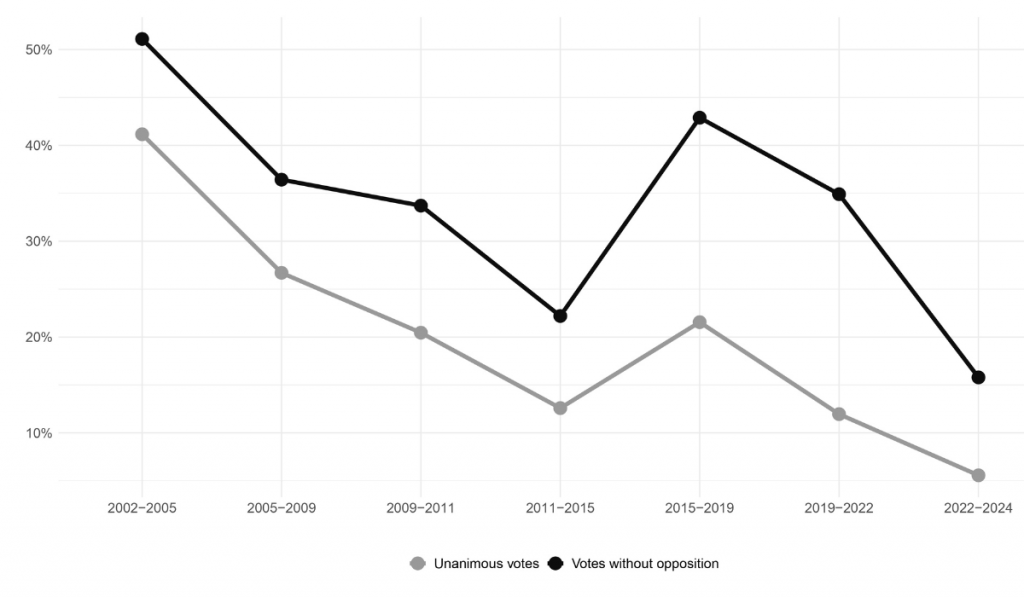

Our analysis of 11,919 parliamentary votes from 2002 to 2024 uncovers three striking findings. First, Portugal's parliament has lost its capacity to achieve consensus. In the early 2000s, over 40% of legislative initiatives passed without opposition votes. Between 2022 and 2024, that figure plummeted to just 5%.

Second, this erosion predates Chega's emergence. Conflict started increasing as early as 2002. It was only interrupted during the geringonça period (2015–2019), a parliamentary contract between radical-left parties and the Socialist government. Then the trend resumed.

Third, confrontation intensified from 2019 onward − and accelerated after 2022. This coincided with the entry into parliament of Chega, Livre (pro-European, left-wing), and Liberal Initiative (IL, economically libertarian). Of these, only Chega experienced a dramatic surge, expanding from one to sixty MPs in just six years. In the recent January 2026 presidential elections, its leader André Ventura finished second and will compete in the run-off in the coming weeks. Long considered Europe’s last holdout against the radical right, Portugal no longer holds that distinction.

Since 2019, Chega has experienced a dramatic surge, expanding from one to sixty MPs and bringing immigration, security, and cultural identity to the fore

Chega's success brought previously peripheral issues of immigration, security, and cultural identity to the fore. This introduced cleavages around themes that had not previously been politically salient in Portugal.

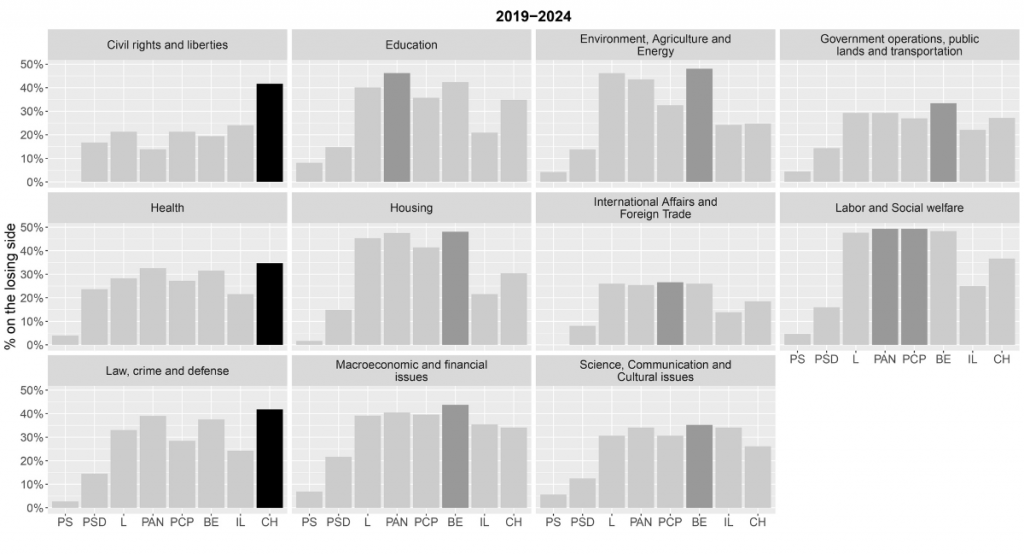

Chega is the party most often on the ‘losing side’ of votes. On rights and freedoms, Chega emerged as the most isolated party. However, the agreements between the governing right-wing coalition and Chega after the May 2025 snap legislative elections may be altering this pattern.

Legislative behaviour does not always follow political rhetoric. For legislative proposals on macroeconomics, finance, and social policies, Chega consistently aligns with the dominant parliamentary consensus. On the contrary, radical-left parties play the main opposition role.

We analysed how each party voted between 2019 and 2024, after Chega entered parliament. Our research used transformer-based models to classify text according to Comparative Agendas Project topics. Throughout this period, the Socialist Party led the government. Direct confrontation between a centre-left government and Chega, an opposition party claiming to be anti-system, thus looked likely.

Yet the data show otherwise. On housing, labour, public finance, and welfare, the party challenging the parliamentary majority is not Chega. Instead, Bloco de Esquerda (radical-left / libertarian), PCP (Communist), Livre, and PAN (environmentalist / animalist) most often find themselves on the losing side. These parties, not Chega, challenge the consensus on macroeconomic and social matters.

Despite its anti-establishment rhetoric denouncing 'socialist policies' in democratic Portugal, Chega's legislative voting patterns reveal a different story on socioeconomic issues. This discrepancy extends beyond Portugal: studies on the European Parliament reveal that other radical-right parties follow similar patterns.

Every party must define its stance toward others, including whether to cooperate in parliament. The entry of a radical-right populist party like Chega should trigger more parliamentary conflict. This seems especially likely since Chega adopts an anti-system stance and advocates replacing the current Portuguese Republic. Thus, we expected this conflict to run both ways: from Chega toward other parties and from other parties toward Chega.

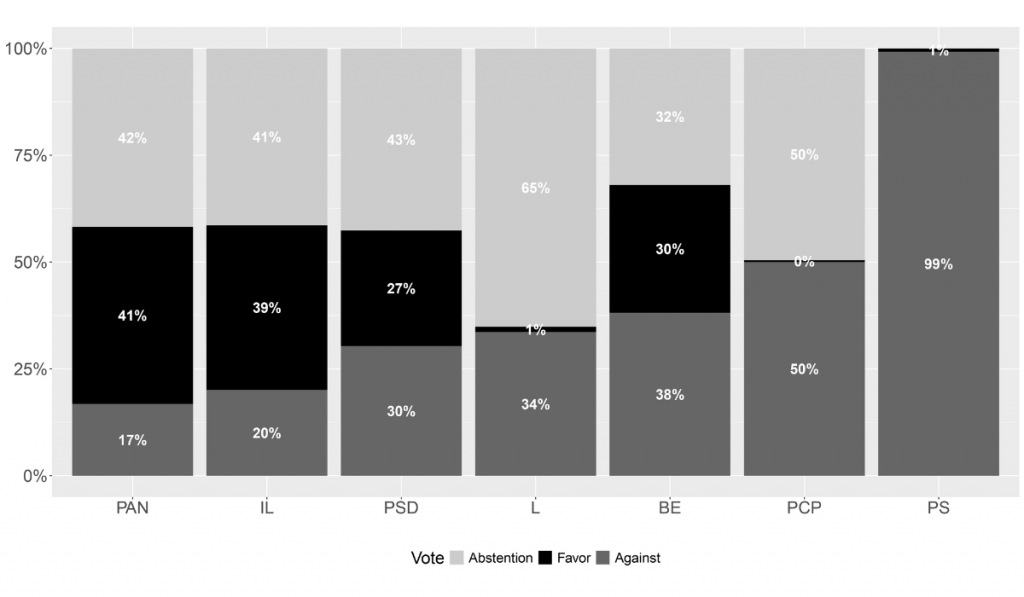

Despite its anti-system stance and vocal opposition to mainstream parties, the party does not behave adversarially toward established parliamentary parties. Chega regularly votes with those ideologically closer to it. The party approves 82% of PSD (centre-right mainstream party) proposals and 80% from IL. Besides that, Chega also approves many proposals from other parties, including the Communists.

Despite its anti-system stance and vocal opposition to mainstream parties, the party does not behave adversarially toward established parliamentary parties

But the reverse is not true. Some parties refuse to support any Chega initiative. This parliamentary cordon sanitaire around Chega signals to voters that these parties consider this party qualitatively different.

Until June 2024, PS, PCP, and Livre took this approach, choosing not to vote favourably on any Chega proposal. On the left, Bloco de Esquerda was the exception, approving around 30% of Chega’s proposals, despite the parties’ ideological divide.

The landscape has since changed. After losing the 2024 elections, the Socialist Party began voting favourably on some Chega proposals under the new leader, José Luís Carneiro. PCP and Livre maintain their rejection stance, as recent data from Frederico Muñoz demonstrates.

The asymmetry is also clear among parties closest to Chega. While Chega approves about 80% of IL and PSD initiatives, reciprocity is much lower. Its own legislative initiatives receive considerably less support from those ideologically closest.

Disagreement is not merely inevitable in a pluralist system; it is a democratic virtue. Politics, after all, thrives on conflict and drama. As Simon Hix wryly puts it, ‘Politics is ultimately a glorified soap opera, with weekly instalments of confrontations and intrigues between vibrant (or sometimes dull!) personalities’. Parliaments are the primary stages for this drama, arenas for opposition and contestation. Yet the way disagreement is articulated and managed reveals much about the health of representative institutions.

For 15 years, legislative polarisation in the Portuguese parliament has increased dramatically. Broad agreement eludes it. The boundaries between confrontation and cooperation shift with each legislature − sometimes with each vote.

Parliaments are arenas for opposition and contestation, but the boundaries in Portugal shift with each legislature − sometimes with each vote

A radical-right populist party can accelerate and intensify parliamentary conflict. Our data shows how Chega was a pivotal actor in this transformation. It introduced a confrontational stance on issues central to its platform (but previously not salient in Portugal), such as civil rights and liberties, law, crime, and defence. It also provoked strong, often adversarial reactions from other parties. For the first time, a parliamentary cordon sanitaire was formed in Portugal’s parliament.

Three consequences stand out. First, the path to reform narrows considerably. Each bill now requires increasingly complex political engineering, affecting especially matters that need large majorities (e.g., constitutional amendments). Second, parliament struggles to project national unity. It appears less as a space for constructive deliberation and more as a stage for division. Third, the distance between parties deepens, making compromise in Portugal’s parliament ever more difficult.