James F. Downes, Mathew Wong and Man Hoo So argue that the European Union-China relationship has evolved considerably over recent years into a growing global rivalry. The EU has become more interventionist towards China, but there exist large divisions in perspective within the core EU institutions and member states

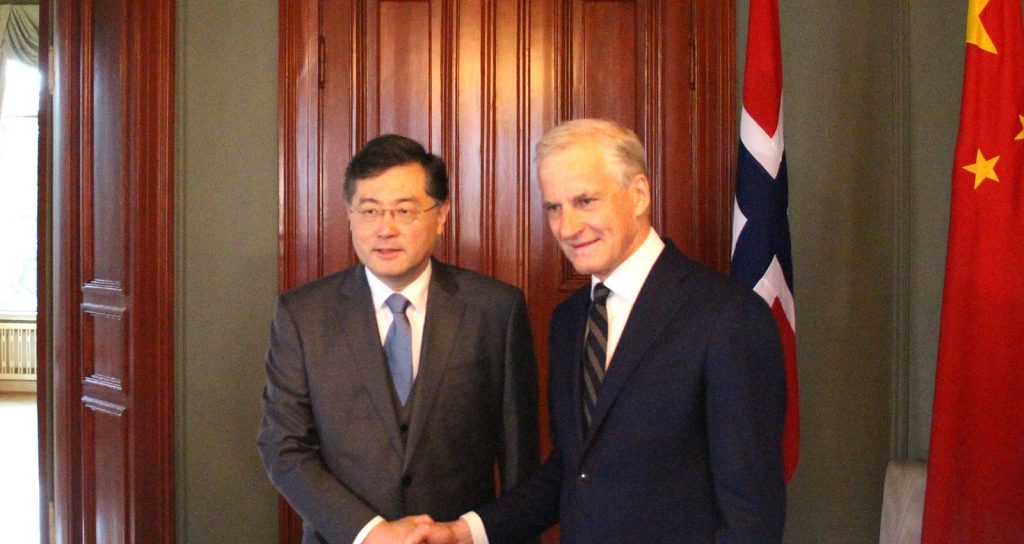

EU-China relations have evolved considerably over the first five months of 2023. The EU sent a high-level delegation to China in April, with French President Emmanuel Macron and EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen making a visit to President Xi Jinping in Beijing. On China’s side, 2023 has seen a new ambassador to the EU in the form of Fu Cong, head of the Chinese Mission to the EU. He has sought a more pragmatic rapprochement with the EU. More recently, in May, China’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang made a visit to Europe, visiting Germany, France and Norway.

The relationship between the EU and China continues to be complex and multi-dimensional. On one hand, China is the EU's second largest trading partner after the United States. EU-China trade volume reached over $1 trillion in 2021. On the other hand, the EU has continuously criticised China over issues including human rights concerns, EU companies' lack of market access in China, and challenges to the international rules-based system.

In 2023, these diverging economic interests shape the dynamics of EU-China relations. We should expect the economic partnership to remain key this year, though with a more cautious and pragmatic approach from the EU. China's growing global assertiveness and strategic competition with the US is also influencing the EU’s stance towards Beijing.

China is the EU's second largest trading partner, but also the subject of much criticism on human rights concerns and other matters

The EU is also working to diversify supply chains and reduce its dependence on China for certain imports through its ‘strategic autonomy' agenda. The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the risks of being overly reliant on China for goods such as medical equipment. The EU will likely aim to reduce these vulnerabilities while maintaining economic cooperation with China where interests align.

Politically, the EU appears to be aligning more closely with the US in response to China's growing geopolitical assertiveness. Notably, it has recently adopted a 'de-risking' economic strategy. Furthermore, the EU has expressed concerns over China's aggressive foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific region.

In addition, EU member states remain divided on taking a tougher stance in their relationship with China. Countries including Lithuania, the Czech Republic and Poland have pushed for a more confrontational EU policy. Meanwhile, other countries such as Italy, Hungary, and Greece have sought to maintain economic cooperation with Beijing. Recent signs indicate that Hungary is becoming increasingly important to China. Germany also wants to avoid decoupling from China, given its considerable trade surplus.

Europe must maintain a delicate balance between its own concerns and alignment with the US, and its cooperation with China in areas of mutual benefit

Another important dynamic is the growing strategic competition between the US and China, which is shaping Europe's own geopolitical calculations. The EU fears the emergence of a bipolar global order, and may want to avoid taking sides in a potential new Cold War. But it also recognises that China's rise threatens cooperative multilateralism, which has underpinned the international global governance system for decades.

Currently, the EU is pursuing an approach of cooperation with China in areas of mutual benefit, including its strategic autonomy agenda. The relationship seems set to remain complex, with economic engagement balanced against growing geopolitical rivalry and concerns over China's authoritarian political system. Both sides have an interest in managing tensions and avoiding outright confrontation. The EU will, most likely, continue to promote its interests, values, and vision of an open, fair, and rules-based global order in its dealings with Beijing.

There are also divided attitudes within the EU’s institutions towards current China policy and the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). The EU Parliament is likely to reject any fresh attempt to ratify the CAI. EU Council President Charles Michel has been touted as wanting to revive the deal. The EU Commission has adopted a more negative, hawkish attitude to its relationship with China during recent times, while French President Macron is taking a more positive, dovelike approach.

Geopolitically speaking, China’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang’s recent visit to Europe may be a part of a wider divide and conquer strategy by Beijing. The idea may be to strategically increase rifts (policy differences) between the leaders of France and Germany alongside the EU Commission under President Ursula von der Leyen.

Beijing may be pursuing a wider policy of 'divide and conquer' towards the EU, stoking policy differences between EU members and institutions

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has, in recent times, deliberately targeted economically smaller, weaker EU countries, such as Hungary and Italy. This, to some extent, caused von der Leyen in late 2021 to launch the EU’s Global Gateway Programme, as a direct policy response to the economic threat posed by China’s BRI.

The EU has become much more interventionist in international politics – a tendency that has been particularly pronounced in the last few months in its dealings with China. During this period, several EU leaders have made overseas visits to Beijing. Since the appointment of ambassador Fu Cong in December 2022, China also appears to have adopted a more positive attitude towards the EU. It is not clear, however, to what extent Beijing's recent moves are genuine policy shifts or mere strategic stalling.

Uncertainty is likely to dominate EU-China relations in 2023. The relationship will depend on the complex interactions of geopolitical and economic trends. It could grow more strained or competitive, but deeper cooperation is also possible, especially on global issues.

This blog post is based on James F. Downes' recent presentation at the Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence workshop Improving Institutional Trust in Times of Pandemics, co-funded by the EU, at Hong Kong Baptist University, alongside James' recent interview for The South China Morning Post. For a more in-depth analysis, see the Global Europe Centre Report.