The people of Chile have rejected two constitutional proposals in little more than a year. Why? Pedro Fierro reveals that there are areas in Chile where residents reject politics entirely. This sentiment transcends ideological divides, and may have significantly influenced both constitutional processes

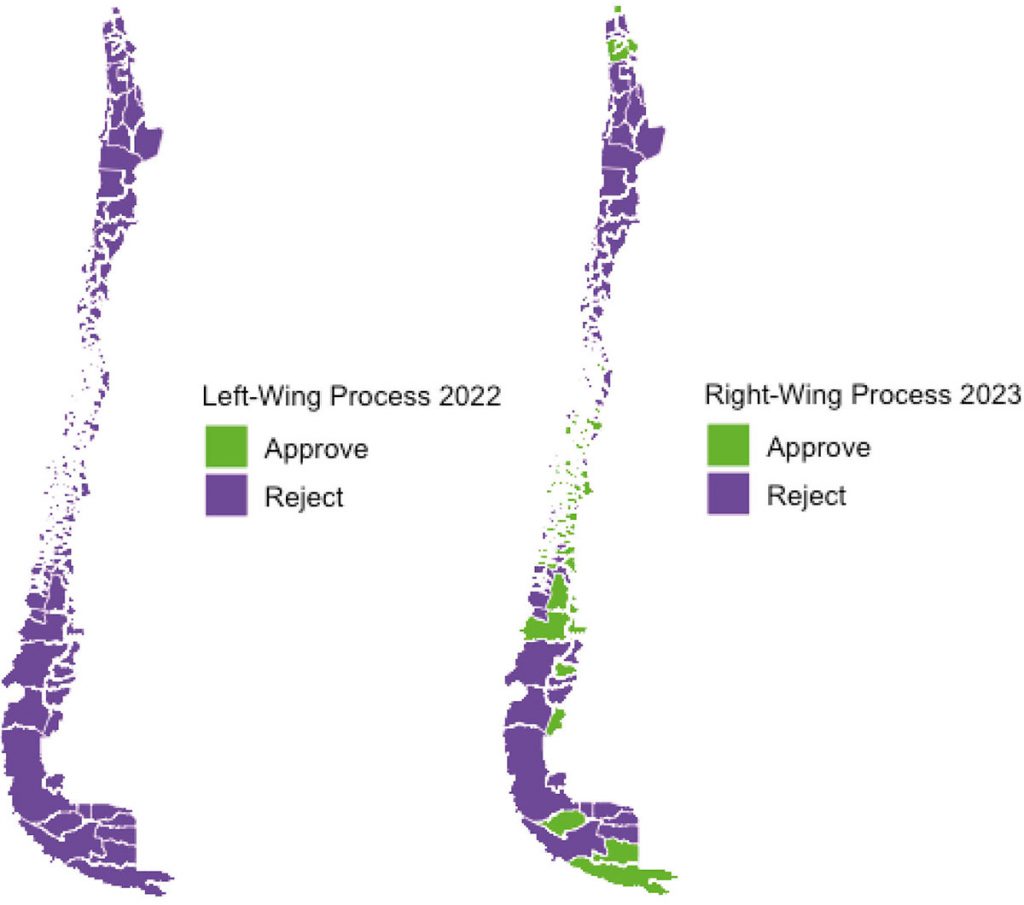

On 17 December 2023, 56% of Chileans voted to reject the constitution draft proposed by the right-wing-led Constitutional Council. This vote came just a year after 62% of the population had rejected a draft by the left-wing-led Constitutional Convention.

Chile is a demographically centralised country. So why do scholars neglect the spatial dimension when analysing voter behaviour?

Voting down two constitutional proposals in such a short time positions Chile as an unusual case globally. In the post-referendum period, various interpretations of these outcomes have emerged, which contribute significant insights to the ongoing debate. However, it is strikingly evident that, in a country characterised by centralism, we continue to underestimate spatial effects when attempting to explain voting patterns.

Some areas of the country appeared to be more influenced by ideology, showing reversed voting patterns between the left- and right-wing proposals. Yet a common trend emerged in the majority of Chilean communes: citizens rejected both processes.

Scholars often overlook the extent of this territorial pattern. In 110 communes — nearly a third of the country — opposition to both proposals varied by no more than 11%. In this context, traditional cleavages used to analyse electoral outcomes are insufficient for a plausible interpretation — and this leads to widespread perplexity and confusion.

Trump's victory, the Brexit vote, and various nationalist projects in Europe were fuelled in part by discontent in the 'left-behind' places

The conundrum is not unique to Chile. Observers around the world have recognised that local contexts influence voter behaviour. Economic geography studies show that Trump's victory, the Brexit vote, and various nationalist projects in Europe were fuelled in part by discontent in the 'left-behind' places, where inhabitants harbour frustration, anger, and powerlessness. According to various scholars, these areas become strongholds for populist projects and anti-establishment narratives.

The challenge, then, is to determine whether this phenomenon is occurring in Chile. To this end, we must establish whether there are indeed neglected areas and, if so, whether the people living there have stored up negative feelings towards the political system.

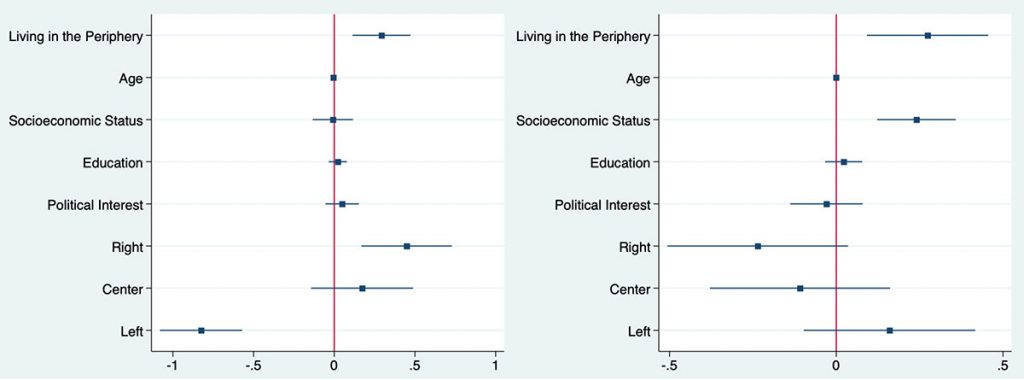

To find out, I analysed 3,300 cases gathered in collaboration with IPSOS and Datavoz-Statcom (two global public opinion companies) in the Chilean region of Valparaíso. Valparaíso is Chile's second-largest region. It is home to the National Congress and was one of the main sites of the massive protests in 2019 that triggered the constitutional process. The data reveal that those living outside the political centre are more likely to feel negatively about both processes, whether they are led by the left or right wing. This is significant because, of all the elements considered in econometric analyses, the only variable that remained constant in magnitude, sign and statistical significance was the territorial one. See the graphs below.

Clearly, this is not the sole reason for the outcomes of the most recent plebiscites. However, it is striking that public discourse has overlooked this aspect entirely. If we agree on this diagnosis, we can address the situation in a number of ways.

During both constituent processes, the Chilean administration could have implemented participation mechanisms more effectively. Given the excessive territorial concentration of the debate, forums often merely served to amplify the voices of groups which already wielded power, and failed to include genuinely marginalised sectors. This affects not only the collected inputs but also the level of engagement from a more attitudinal and emotional dimension.

A 'Deliberative Town Hall' experiment involving thousands of Chileans improved trust and interest in the democratic system — even among participants from 'left-behind' areas

The second constituent process took place in 2023. During this process, Ohio State University and the right-wing Chilean organisation Fundación P!ensa conducted an experiment involving nearly 3,500 citizens from across Chile. Participants engaged in deliberative sessions with constitutional delegates from both political sectors. The experiment, which also included a control group of 10,000 citizens, was randomised, and based on inclusion and dialogue.

The architects of this experiment engineered the dynamic to force some agreement, and its results were telling. The outcome was an increase in democratic indicators — emotions, trust, interest, and various other attitudes — among participants, including those from marginalised areas.

The key, therefore, may lie in the mechanisms of participation and deliberation. For now, we must pause and reflect upon the diagnoses made to date. And we mustn't underestimate how the context of each neighbourhood, city, and region influences opinion. In Chile, it appears that there are indeed neglected places, where citizens form judgements and emotions that are harmful to democracy. If we don't take this seriously now, it may be too late.