Elizabeth Kaletski and Susan Randolph explore the inherent links between human rights and the economy. They argue that economic and social rights (ESR) and economic growth are mutually reinforcing, and that prioritising ESR may be the best path towards improving both

Human rights and the economy are inherently linked. But how?

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) sets out rights, and requires countries to devote their maximum available resources to progressively realise them. This formal commitment has often led to improvements in ESR over time. But some are concerned that the focus on human rights comes at the cost of reduced economic growth.

Some argue that prioritising issues other than the bottom line – such as education, housing, or other human rights – reduces profit and growth

In some countries this has evolved into political opposition to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks. ESG pushes the public and private sector to consider the impacts of decision-making beyond short-term financial concerns. Some argue that prioritising issues other than the bottom line – such as the education of the workforce – reduces profit and growth. But empirical evidence remains inadequate.

Eduardo Burkle argues that we can use human rights data to better understand country performance and identify effective policy. Therefore, we use the Human Rights Measurement Initiative’s (HRMI) quality of life index, also known as the SERF index, to do so.

The language of the ICESCR implies that ESR, rather than growth, should be the priority of state parties. It also implies that that steps taken to meet ESR obligations may conflict with those that best support economic growth – and vice versa. For instance, technological innovation is essential for promoting growth. But if that occurs by concentrating government investment on higher education, it leaves fewer resources to expand access to education.

Conversely, policies that promote high quality education fulfil the social component of ESG and the right to education. But they can also benefit businesses and the broader economy because an educated workforce is more productive. Given the potential theoretical connections, we explore the relationship between countries' enjoyment of ESR and their economic growth record.

The ICESCR sets out the economic and social rights to which all human beings are entitled, based on their inherent dignity. These include access to basic goods, services, and opportunities necessary to reach their full potential. HRMI’s income-adjusted ESR metrics focus on the rights to education, food, health, housing, and work.

The measures use internationally comparable and publicly available data. They cover 194 countries from 2000–2020 (though coverage varies depending on the right). The data include metrics for the five individual rights, and an overall quality of life index. We use the income-adjusted version. This is identical to the SERF data, and measures how countries perform relative to their economic resource constraints.

We combine these ESR scores with per capita GDP annual growth rates from the World Development Indicators to examine patterns in country performance from 2010 to 2020. Using an established methodology, we separate countries into four categories along two dimensions – ESR fulfilment and economic growth.

Those that perform better than the median in the year concerned on both rights fulfilment and economic growth are classified as virtuous. This is the best-case scenario. Those that perform worse than the median in the year concerned on both are classified as vicious. Those with a score above the median for ESR but below the median for growth are ESR-lopsided. The reverse situation is growth-lopsided.

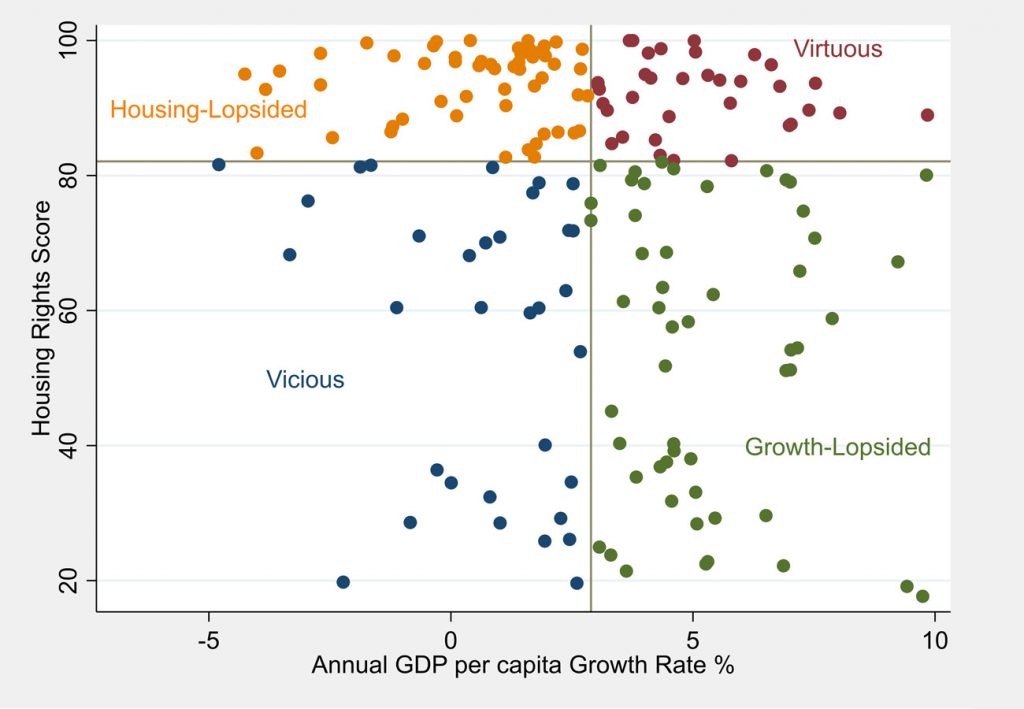

Based on this categorisation, using housing scores as an example, the figure below shows the starting position of each country in 2010. The horizontal and vertical lines indicate the median housing score and GDP per capita growth rate, respectively.

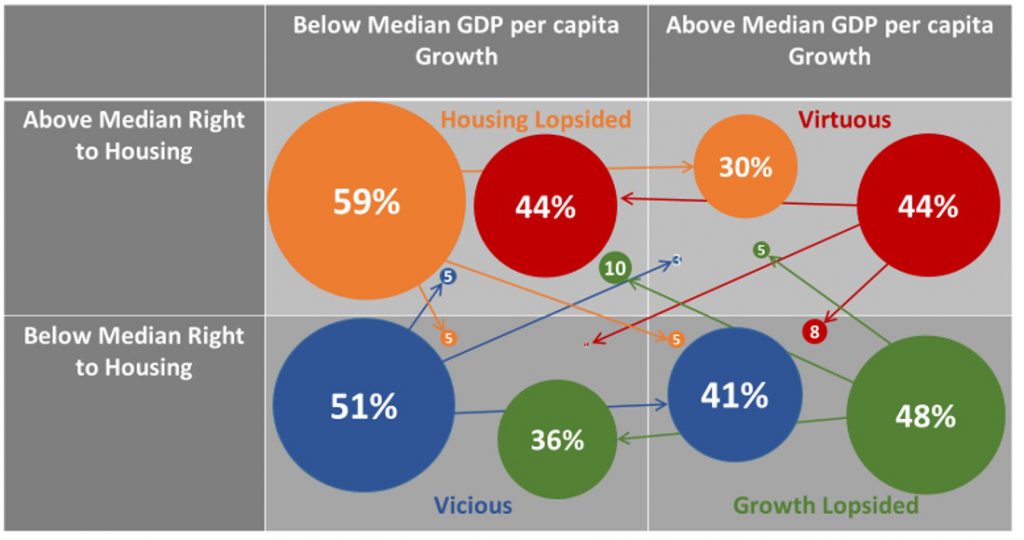

Given their starting position in 2010, we then track where each country ends up in 2020. The blue circle in the bottom-left quadrant of the figure below indicates that 51% of countries that begin in the vicious category in 2010 remain there in 2020. Similarly, 44% of countries that begin in the top-right virtuous quadrant remain there.

A high percentage of countries that begin in either the vicious or virtuous category stay there. Once a country falls into the vicious category it is difficult to escape, but if it can reach the virtuous category the benefits can be enduring.

The orange circle in the top-left quadrant indicates that 59% of countries that began as housing-lopsided in 2010 remain there in 2020. The arrows to other quadrants show the percentage of countries transitioning to different categories over the period – 5% move to vicious, 5% to growth-lopsided, and 30% to virtuous.

Similarly, the green bubble in the bottom-right quadrant reveals that 48% of countries that begin in the growth-lopsided category stay there, while 5% transition to virtuous, 10% to housing-lopsided, and 36% to vicious.

In the absence of ESR fulfilment, maintaining rapid economic growth is difficult

Countries that begin as ESR-lopsided are most likely to either remain there or transition to the virtuous category. Thus, countries that do a better job of fulfilling their commitments under the ICESCR tend to enjoy a growth benefit in the subsequent decade.

In contrast, countries that begin as growth-lopsided are most likely to either remain there or transition to the vicious category. So, in the absence of ESR fulfilment, maintaining rapid economic growth is difficult.

These patterns are robust across separate analyses for each of the five rights and the overall quality of life index.

These results show that there does not appear to be a conflict between fulfilling economic and social rights and economic growth. Rather, ESR fulfilment and growth are mutually reinforcing. These data provide evidence that current discussions around ESG and broader concerns about prioritising human rights over growth may be overblown.

Furthermore, the best path towards the optimal category, in which a country performs well on both ESR and growth, occurs by prioritising ESR fulfilment. The mechanisms through which this occurs remain in question. But human rights data should be used to identify specific policy prescriptions in pursuit of this positive outcome.