Evidence-informed policy-making promises to deliver better policies. Yet, people working at the science-policy interface in Europe face multiple challenges in making the most of it – from political constraints to a lack of administrative capacity and limited opportunity for productive exchange. Giuseppe Cannata discusses these challenges and their normative implications for European science-for-policy ecosystems

Over the past few years, the idea that governments need sound evidence to inform public decisions has gained momentum across Europe. In Brussels, where the European Commission has long maintained an in-house knowledge service, the Joint Research Centre (JRC), there have been several initiatives to this end.

In 2021, for instance, the Commission reviewed the so-called Better Regulation Guidelines – the guiding principles of law-making in the EU. This revision made evidence-informed policy-making a key tool in the EU’s regulatory toolbox. In parallel, EU institutions published a number of programmatic documents advocating the development of stronger science-for-policy ecosystems.

In a context where trust in governments is on the wane and policies are becoming increasingly complex, evidence comes as a providential fix

Yet, as the vivid debates sparked by the recent pandemic once more showed, science is not immune to being challenged, and expertise can be contested. It is no longer enough – if it ever was – to merely claim that 'it is what science says' or to ‘follow the science’. Fast-paced decision-making, shrinking administrative capacity, and increasing polarisation often render the use of scientific evidence untimely or contentious – or both. Moreover, scientists’ unease about ‘speaking policy’ makes evidence-informed policy-making an even more daunting job.

Conventional wisdom holds that the thornier policy problems get, the more evidence we need to work out how to solve them. In practice, however, the relation between science and policy is not so straightforward.

We often treat science and policy, even in academic debates, as self-contained communities. Scientists and policy-makers speak different languages, have distinct cultures, and pursue different, even contrasting, goals. However, interactions and 'border crossings' do occur, in an often unsystematic and informal manner. The frontiers between science and policy are porous, and problems and solutions spill over. Science trickles down – or up, or even sideways – into policy-making, whether in the form of ideas about how the world works or a news article on a bureaucrat’s desk, creatively summarising some research findings. In turn, policies shape the conditions for knowledge production and the validation of science. Consider, for instance, the rules for academic career progression or research funding.

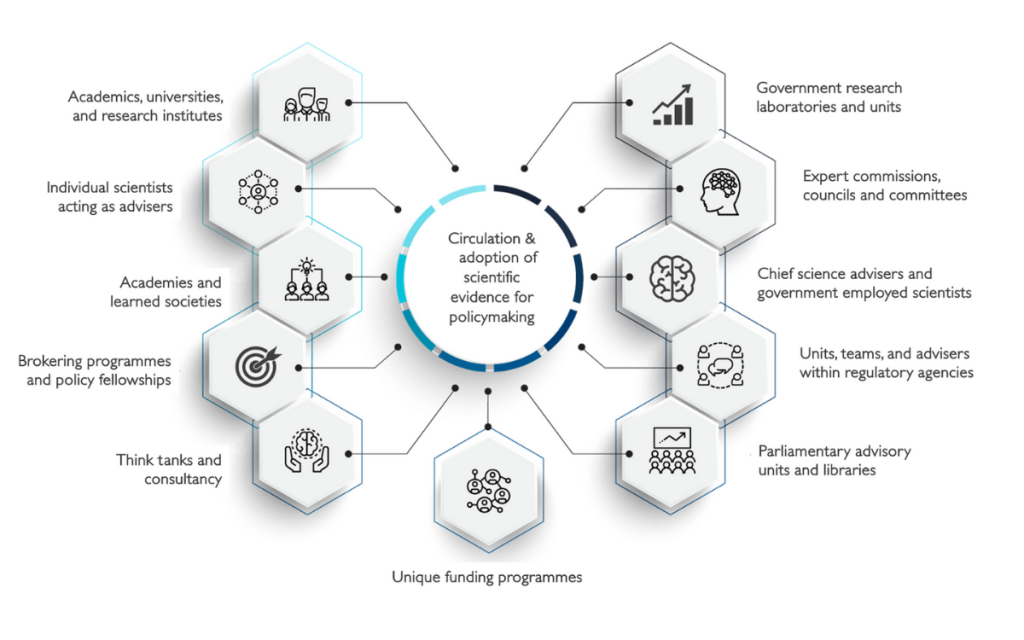

Rather than islands, we can better understand science and policy as existing within a complex ecosystem. Diverse actors, mechanisms, functions, and practices interact in science-for-policy ecosystems to produce and circulate knowledge for policy-making. This perspective shifts the focus from individual actors and practices to their interactions and the normative foundations of science-for-policy. But how do these ecosystems work? What are their qualities and the challenges they face?

Diverse actors, mechanisms, functions, and practices interact in complex science-for-policy ecosystems to produce and circulate knowledge for policy-making

To answer this question, in a recent JRC report we asked the very people working between science and policy. A key challenge, according to the professionals surveyed, is the lack of institutional spaces and meeting opportunities: scientists and policy-makers seldom talk to each other. Second comes the perceived lack of coordination, which can lead to duplicated efforts and loss of valuable knowledge. Political constraints, time pressure, and insufficient competencies on the public administration side complicate the matter further. Science, on the other hand, is often perceived as not ‘fit for purpose’ or not timely enough.

Overall, we found a wide agreement on the main challenges across professional groups (knowledge users, producers, and brokers), with knowledge brokers being the most critical about the shortcomings of science-for-policy ecosystems. Even though this first exploratory survey has some limitations in terms of sample size and representativeness, it spotlights a key function of the science-for-policy ecosystem: knowledge brokerage and intermediation. If science and policy speak different languages, ‘translators’ have a crucial role to play.

While writing this short piece, I realised that it was also about me. Well, not just me. But me as someone wrapping their head around policy-making on a daily basis and, for a little while, a visiting researcher at the JRC. Policy-oriented research is what we – people in academia – do from the sidelines. It is the business of think tanks and consultancies, of those who trade in solutions and do not indulge in science for science’s sake.

Often, however, this idea hinges on the obstinate myth that science can do without politics. But knowledge is not produced in a void, not even behind the aseptic walls of a laboratory. It exists in context: precisely, a socio-cultural context that validates it as science, and legitimises it as evidence.

Informing policy with evidence is a political choice

This does not mean that we can conflate science and policy in an indefinite amalgam. It means, however, that considerations about the inherent political dimension of doing and using science for policy are of key importance. This is not just a matter of supplying knowledge for policy but of assembling politically viable, fit-for-context solutions, while managing the tensions between 'honest' brokerage and advocacy. It is paramount, thus, to communicate where the boundaries between academic research, regulatory science, and other forms of knowledge are drawn, and what guides decisions. Informing policy with evidence is a political choice. And so is the choice of developing institutions, skills, and incentives to make it work (better).

After all, politics is in the research funding we compete for, in the metrics we use, and in the assumptions we all make. If science cannot do without politics, maybe it is time to think seriously about how it can ‘do with’ it.

Hi Giuseppe,

Apologies if I missed your request on LinkedIn—it’s been a busy week with many requests due to the organization of a research festival.

I really like your publication, and I am also a member of the Loop. If you're interested, we could suggest a joint post for the Loop focused on EU policy-making.

Best wishes,

Morgiane