Can policymakers expect people to comply with official health restrictions out of fear rather than because they trust the government? Ben Seyd suggests the answer is no. Governments still need trust to motivate citizens to comply with important collective rules

Many people have drawn a key lesson from the coronavirus crisis of the past two years – that it is deeply important for people to trust in public actors and institutions. Trust encourages people to comply with official rules and restrictions designed to reduce health risks, and stimulates uptake of recommended behaviours such as vaccination.

But is trust as important as often claimed? After all, levels of trust in countries like Britain are fairly low. Despite that, public compliance with official coronavirus restrictions at the pandemic’s outset was high. British people may have taken a dim view of their government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic. Yet most still stuck to the government’s lockdown restrictions.

One explanation for this is that people were frightened of contracting Covid-19. Previous studies have shown that fear is a powerful predictor of compliance with public health measures, such as wearing a protective face mask. Maybe people followed coronavirus restrictions because they were scared of the consequences if they did not comply, rather than because they trusted the governments introducing those restrictions?

Did people follow coronavirus restrictions only because they were scared of the consequences of not doing so?

Previous studies also demonstrate that the relationship between fear and trust, on the one hand, and restriction-compliant behaviours, on the other, is conditional. That is, the impact of trust on compliance is greater when people are less fearful of Covid-19. Where people are more fearful of infection or illness, the impact of trust on compliance is reduced.

Yet how does this conditional effect play out over time? We might suppose that people would be particularly fearful of a new virus at a pandemic’s outset. If so, perhaps these fears motivated people to comply with stringent lockdown measures when they were introduced. As time progressed, however, and people became more familiar with the virus, fear might have waned. As it did, perhaps the way opened for trust to play a stronger motivating role?

This suggests fear and trust are both important triggers of people’s compliance with public health measures. Yet their roles might kick in at different stages. In the early stages of a pandemic, fear might do a lot of the work. but as a pandemic progresses and initial fears among populations wane, trust might ‘take up the slack’ in motivating public compliance.

We might expect to see trust 'take up the slack' over time, as initial fears among the public wane

In a recently published article co-authored with Feifei Bu, I explored the changing effects of people’s fear and trust on their compliance with coronavirus restrictions. Our study focused on Austria, Britain and Germany, using data collected at seven points over an eleven-month period, from April 2020 to February 2021.

When we modelled the association between fear, trust and compliance at each of the seven survey waves, we found the expected conditional effects. As people’s fear of Covid-19 increased, the association between trust and compliance declined. Trust was strongly associated with compliance only among people with low levels of fear.

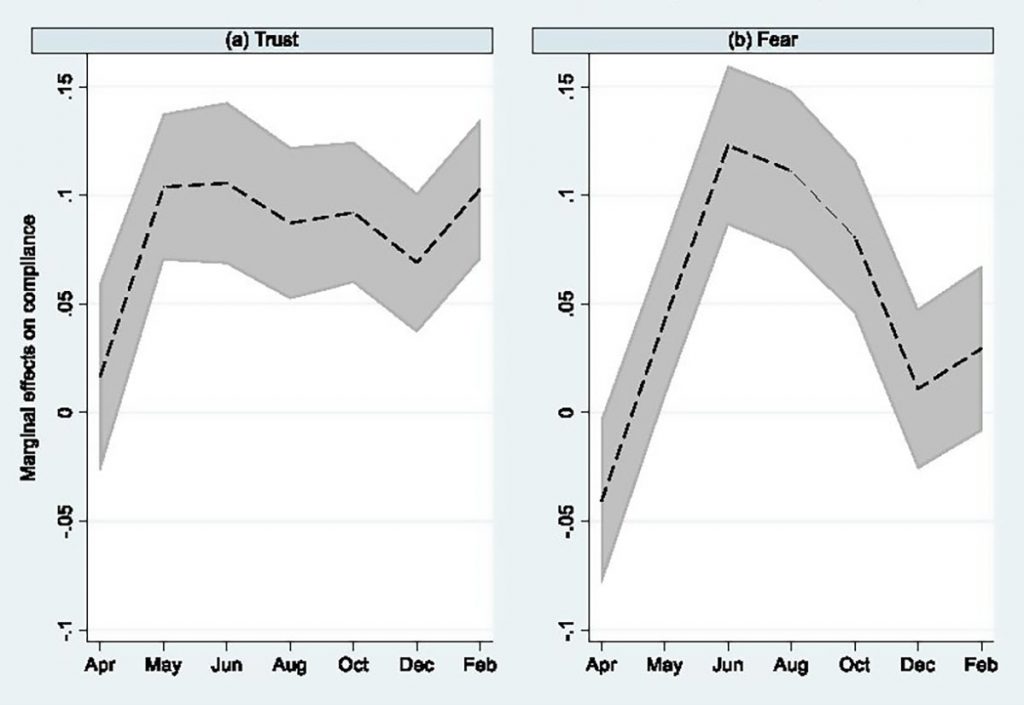

Yet these findings did not translate into a picture over time where fear shapes compliance at the early stage of the pandemic, with trust taking over later on. Graphs of our results reveal how the effects of fear and trust on compliance changed over the eleven-month period. Let us take Austria as our example.

We start with the effects of fear. As the right-hand panel of the graph below shows, the association between people’s fear of the coronavirus and their compliance with official rules increased markedly between April and June 2020. The association then declined to December 2020. This is exactly what we expected. Fear plays a substantial role in motivating compliance in the early stages of a pandemic. Its influence then wanes as the pandemic progresses.

At which point, we should find stronger effects of trust on compliance. Except that we do not. Instead, the association between trust and compliance (left-hand panel) also strengthens in the early stages of the pandemic. The effects then vary a little, but only increase again right at the end of the period, in February 2021.

There is thus little evidence to suggest that trust is only a motivator for people to comply with coronavirus restrictions at points in the pandemic in which fear is doing little work. Instead, fear and trust appear to work in tandem. At the start of the pandemic, the associations between compliance and people’s fear and trust increased substantially. Since then, the effects of fear appear to have waned. But trust has not stepped in to take up the slack.

Fear and trust work in tandem; the latter does not compensate for the former, when it decreases

The results from Britain and Germany fit the same broad picture. Across the three countries, we find no evidence that, at the start of the pandemic, fear rather than trust drove compliance with coronavirus restrictions. Nor is there evidence that, as the pandemic progressed, any increases in the association between trust and compliance reflected waning associations between fear and compliance.

What do these results mean, and what are their implications for policymakers eager to prepare for any future viral pandemics? People’s fears of a virus do not ‘crowd out’ their feelings about government actors in determining whether or not they should comply with official health restrictions.

Governments therefore cannot rely on fear alone to motivate people to behave in pro-social ways. Instead, people also comply with collective restrictions because they trust those responsible for those rules. One of the best preparations that governments can make for any future health emergency is thus to make themselves more trustworthy in citizens’ eyes.