Changing German attitudes to the coronavirus, as measured in original survey data, are the key to understanding how long the country’s success in tackling the pandemic may last, write Jay N. Krehbiel, Amanda Driscoll, Michael J. Nelson and Taylor Kinsley Chewning

Despite the country’s initial successes and the warnings of political leaders and health officials, Germany, along with much of Europe, is in the grip of a second wave of coronavirus infections.

While protests against pandemic restrictions in major cities across the country sparked fears of a coronavirus resurgence, it has been day-to-day activities like family gatherings and summer vacations that worry officials. As the president of the German doctors' union warned, 'There is a danger that we will lose the successes that we have achieved in Germany so far in a combination of repression and longing for normality.'

'There is a danger that we will lose the successes that we have achieved in Germany so far in a combination of repression and longing for normality.'

Susanne Johna, president, Marburger Bund, august 2020

This 'pandemic fatigue' – a sense of frustration with restrictions and complacency about the virus’ threat – has the potential to undermine the efficacy of governments’ efforts to limit the pandemic’s spread.

To evaluate the attitude of Germans towards coronavirus, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of 4,400 Germans in late April and then nearly 3,700 of those same people again in July.

We asked respondents to indicate how scared they are of contracting coronavirus, with answers ranging from 'very scared' to 'not at all scared'. By asking the same people to answer this same question in April and July, we can see who became less concerned by the virus over the course of the summer.

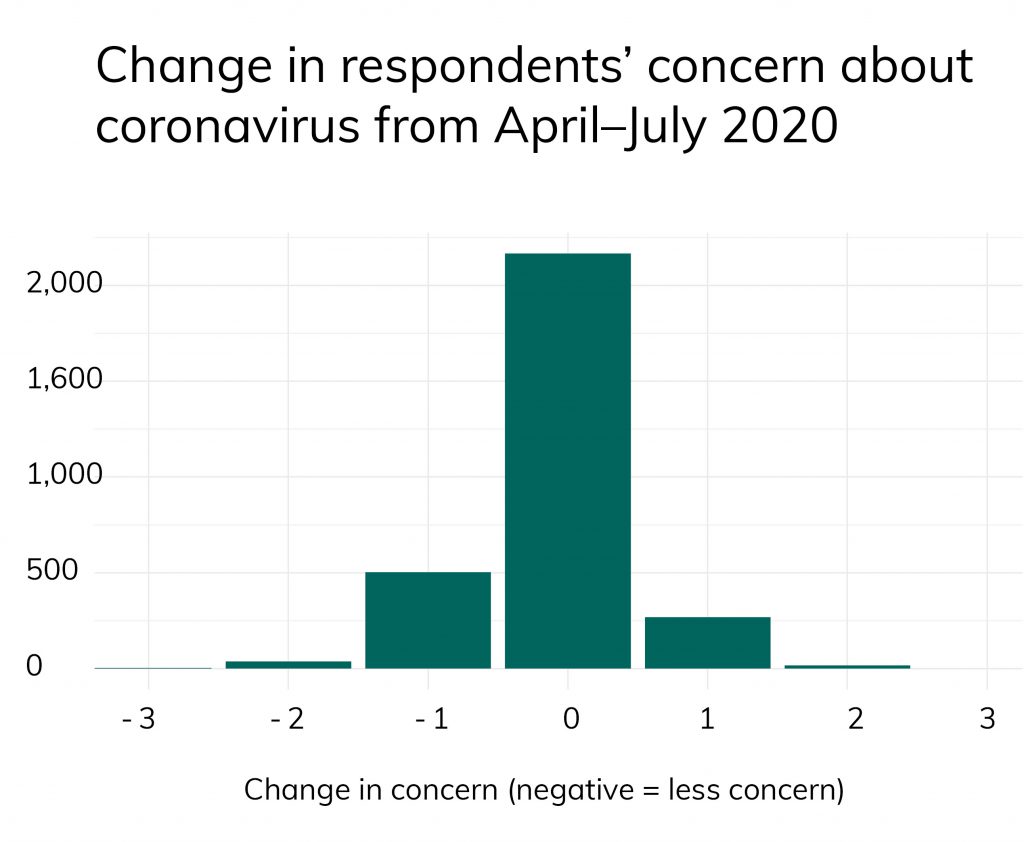

The histogram below shows how much and in what direction our survey respondents’ views of the pandemic changed.

We highlight two observations evident from the figure. First, the majority of respondents remained equally as concerned about the contracting the virus in July as they were in April. For some this means they were and continue to be afraid, while others may have been sceptical of the virus’s threat in April and continue to be so. Second, our respondents have, on average, become less scared of the virus. This is precisely the type of complacency that worries German officials.

Who are these people who have become more comfortable with the spectre of coronavirus? We dug deeper, and examined how respondents’ age, state of residence, and political party preference predict shifts in their fear of contracting the virus.

We also accounted for the respondent’s gender, whether they had a college degree, whether they lived in an urban, suburban, or rural community, and whether the person lived in the former German Democratic Republic (Soviet Bloc East Germany) prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall.

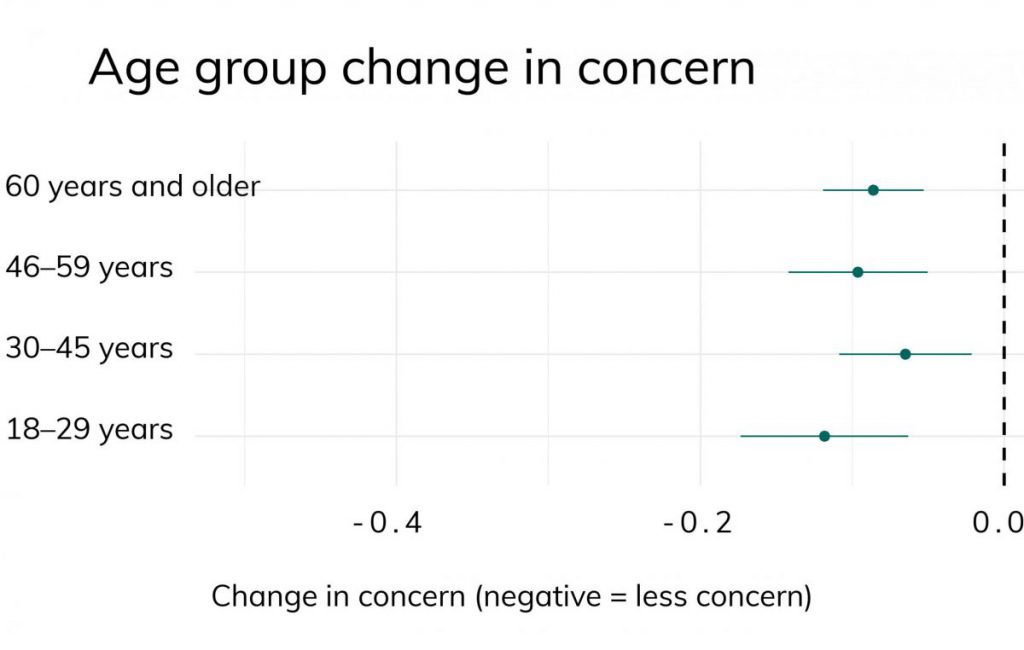

We found a widespread, but shallow, decrease in concern that crosses political, geographic, and demographic lines. For example, even though much attention has been focused on concern that young people will dismiss the virus and resume potential ‘super-spreading’ social activities, we find that all age cohorts in our data have become less scared of contracting coronavirus. And while the largest drop was among youngest respondents (18 to 29 year-olds), this decrease was not statistically different to that of older respondents.

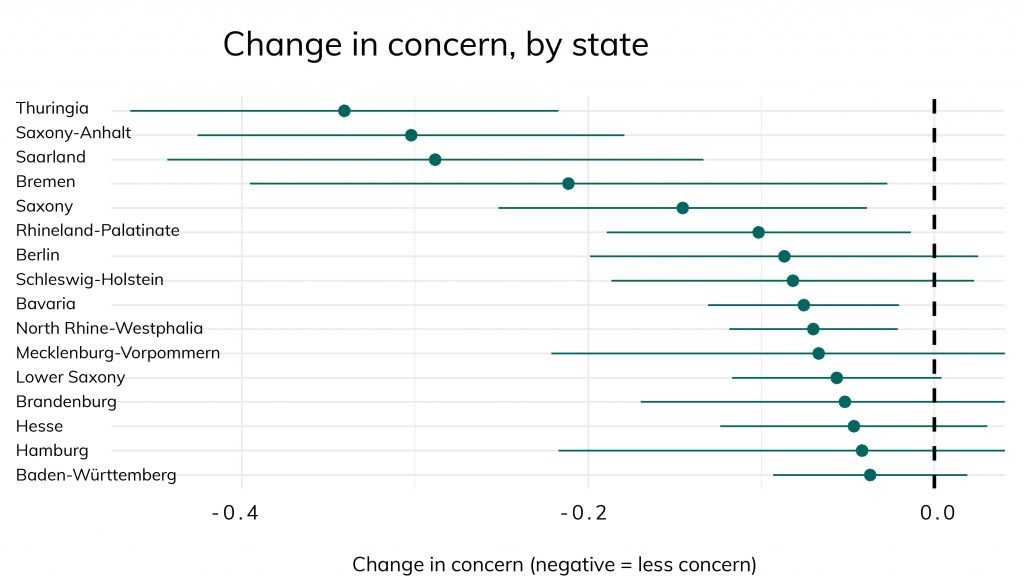

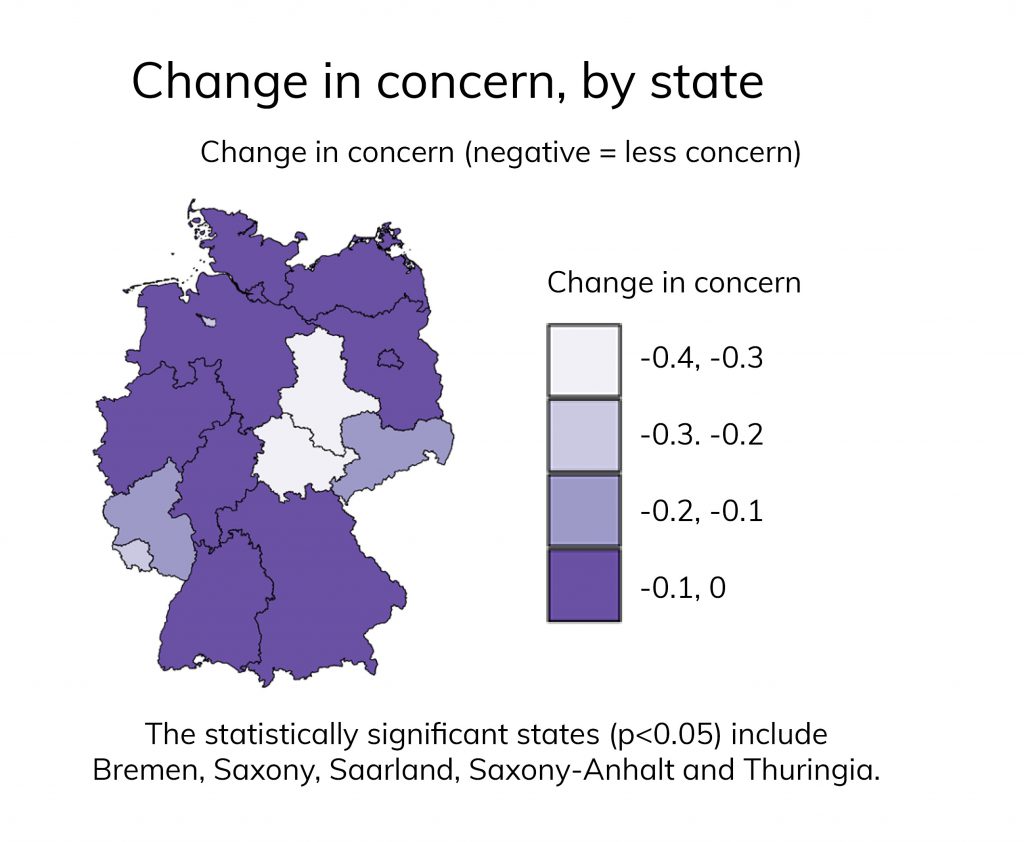

The picture across Germany’s sixteen states tells a similar story. In half of the states, we observe a statistically discernible drop in concern. The largest drop occurs in the eastern state of Thuringia; the smallest is in hard-hit Bavaria.

Notably, we find declines in widely different states. Citizens have become more complacent in five western states, including slightly so in the country’s two most populous (North Rhine-Westphalia and Bavaria) and considerably so in the two least populous (Bremen and Saarland). That said, the most significant declines are found in two eastern states, Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt, where state governments have resisted enacting or enforcing strict coronavirus restrictions such as mask requirements.

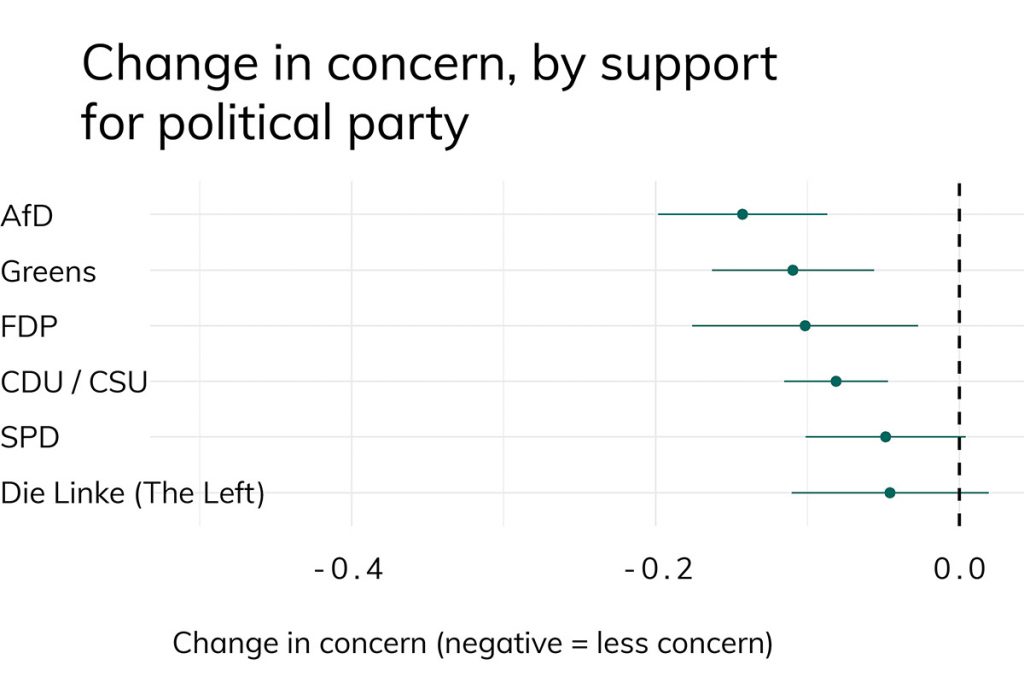

Looking at respondents’ political preferences similarly reveals a declining concern for coronavirus across the political spectrum.

While this decline is greatest among those who identify with the far-right (and coronavirus-sceptic) Alternative für Deutschland it is not statistically different from the changes reported by supporters of the other major parties.

Arguably more surprising is that the supporters of three other parties – the Christian Democratic / Christian Social Union, the Greens and the neoliberal Free Democrats – also report statistically significant declines in fear of contracting coronavirus. This is understandable since the pandemic has not been nearly as politicised in Germany as it has in the US. But it also points to the challenge facing Germany’s leaders, because it appears that something transcending political divides may be driving citizens’ complacency.

Taken together, our findings align with the worries expressed by Germany’s leaders. While the majority of our respondents did not alter their view of the virus, there is clear, albeit limited, evidence of coronavirus fatigue.

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of our findings is that this fatigue is present throughout society. That said, the virus’ recent resurgence may reinvigorate public vigilance. But if it does not happen, Germany’s so-called coronavirus success story might well begin to change.

The research in this blog piece is part of a larger National Science Foundation-funded project entitled Covid-19, Crisis & Support for the Rule of Law.

The purpose of the project is to 'examine the conditions under which public support for the rule of law might thrive, multiply or wither on the vine' following the exogenous shock of the coronavirus pandemic.

Other research from this project by Driscoll, Krehbiel and Nelson shows that once the stay-at-home mandate was lifted in Germany, people with lower incomes went out to work while other people stayed at home.

Teaching modules based on the project data are available and provide a compelling way for undergraduate students to interact with a subject that is happening in real time.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. SES-2027653, SES-2027671, and SES-2027664. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. These surveys were reviewed and cleared by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board.