The rich are more likely to vote than the poor. This, along with income inequality, are increasing phenomena across the West. Matt Polacko introduces supply-side logic to reveal that higher levels of income inequality are indeed associated with reduced voting rates, and a wider income gap in turnout. However, it is possible to mitigate both effects with greater policy choice

According to conflict theory, rising income inequality increases the demand for redistribution, which should increase the political participation of the poor. Yet the evidence for conflict theory is sparse. This may be because it overlooks the supply side in the inequality-turnout relationship: the policy choices on offer (policy polarisation).

When greater economic policy choice is offered, this gap is significantly reduced through greater participation of low-income earners.

I investigated three hypotheses using a Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) sample. Data comes from 30 advanced democracies, in 102 elections between 1996 and 2016.

First, in line with previous research, I found evidence for 'relative power theory' – that increased income inequality leads to lower turnout, particularly among lower income individuals. This increases the income gap in turnout.

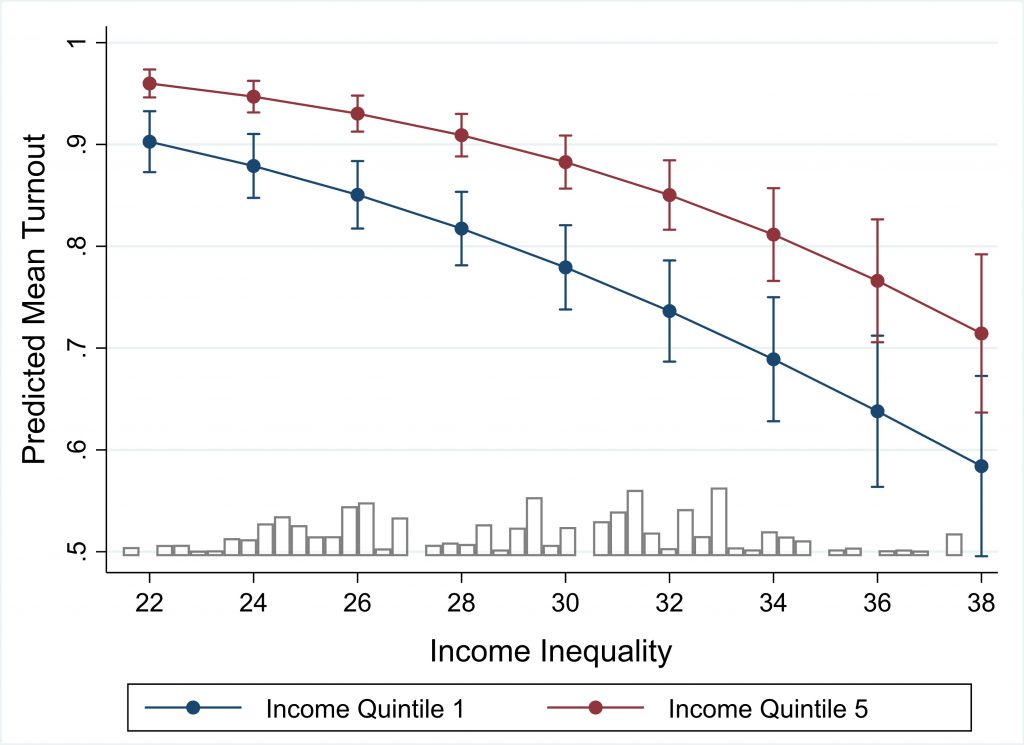

Figure 1 shows that as inequality increases, the likelihood of voting significantly decreases for the lowest and highest income quintiles. Moving from the lowest to highest levels of income inequality, the income gap in turnout more than doubles, from roughly 6 to 13 percentage points.

The income gap in turnout tends to be widest in countries with the most inequality, such as the UK and US. These countries, however, also tend to have lower levels of policy polarisation.

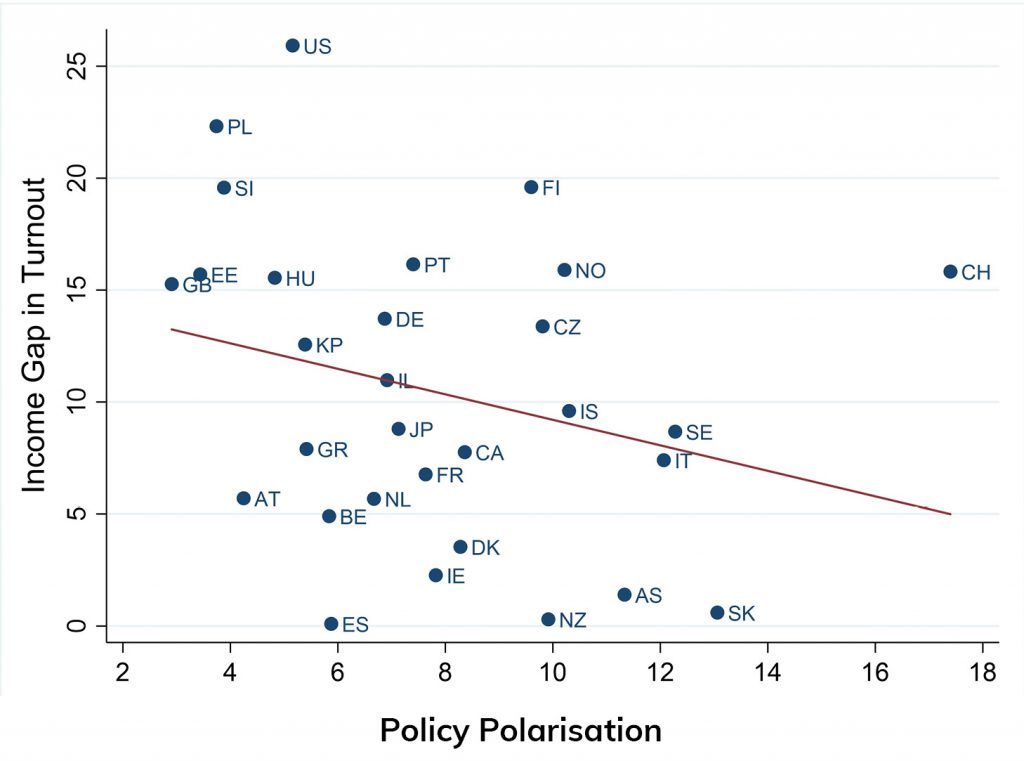

I compared these using policy offerings on redistribution from the Comparative Manifesto Project (MARPOR). Figure 2 presents the cross-national average aggregated income gap in turnout, by policy polarisation.

Moving from countries with the lowest average levels of policy polarisation to those with the highest, the income gap in turnout declines from roughly 13 to 5 percentage points.

Second, I found evidence for 'conflict theory'. By this I mean that increased inequality leads to higher turnout, but only when party systems adopt greater redistributive policy choice.

increased inequality leads to higher turnout, but only when party systems adopt greater redistributive policy choice

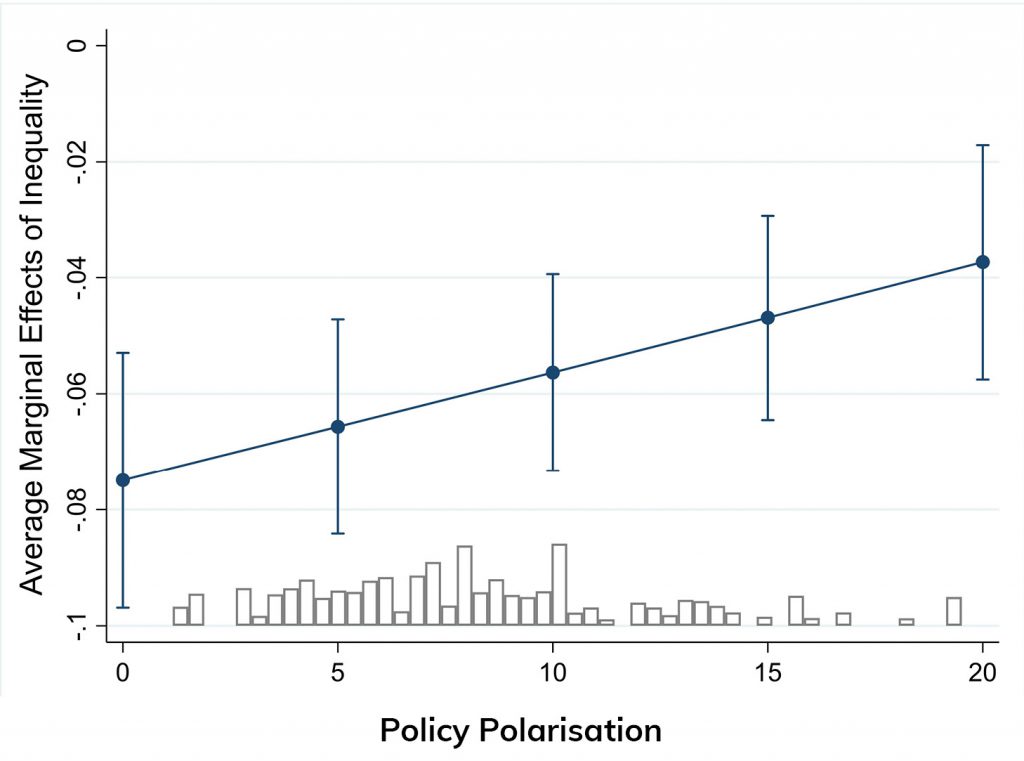

Figure 3 shows that in highly polarised systems, turnout does not vary much by levels of inequality. In depolarised systems, however, turnout is much lower when inequality is high.

At low levels of inequality, turnout is somewhat higher in depolarised systems than in polarised systems. When inequality is high, turnout is higher in polarised systems.

Third, I found that income inequality leads to a greater income gap in turnout when parties adopt less redistributive policy choice. This effect, in turn, is mitigated with greater redistributive policy choice.

The reason for this is that increasing inequality places greater saliency on redistribution. This leads to greater divergence in the economic policy preferences of low- and high-income earners.

However, it is low-income earners who are typically much less likely to vote and who receive the least political representation. This effect is even more marked in contexts of higher income inequality.

low-income earners are typically much less likely to vote – and receive the least political representation

Thus, low-income earners are most mobilised by greater economic policy choice in the context of higher inequality.

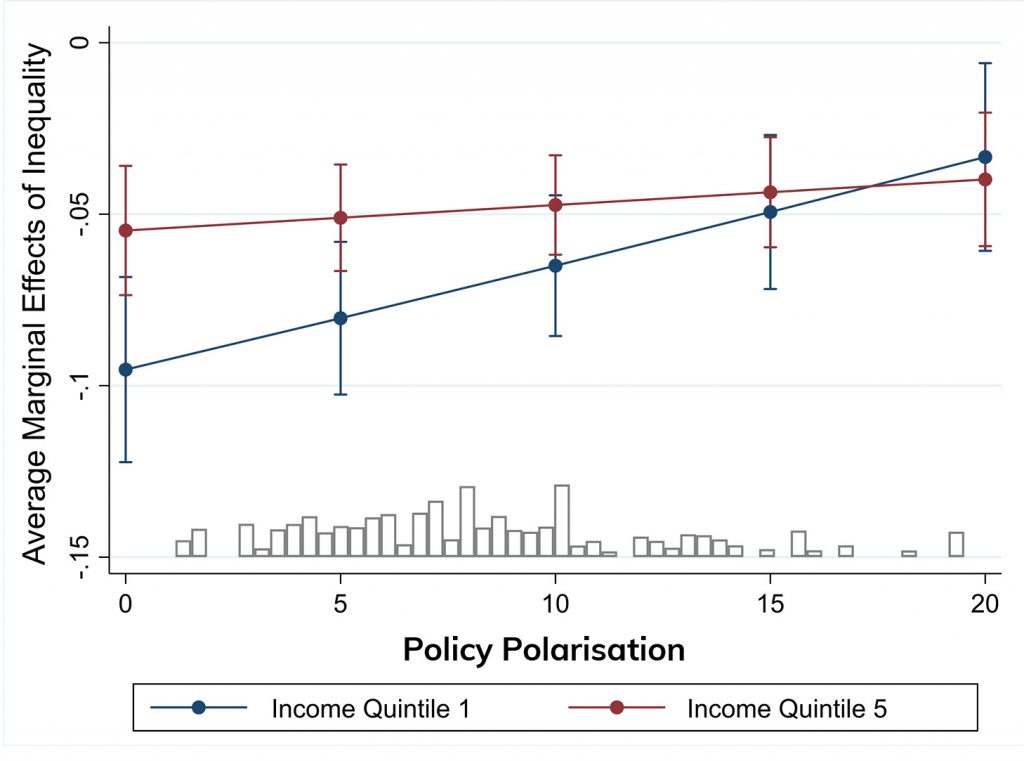

Figure 4 illustrates these effects. Inequality reduces turnout at both low and high levels of polarisation, regardless of income.

Most importantly, however, at low polarisation, inequality is much more likely to reduce the participation of people on low incomes than those on high incomes. At the highest polarisation levels, inequality is slightly less likely to reduce the participation of the poor than the rich.

In substantive terms, inequality is associated with a roughly 0.7% increase in turnout for the bottom quintile when moving from the lowest to highest level of policy polarisation. For the top quintile, however, it accounts for an increase of only about 0.1%.

My recent co-authored aggregate-level research in the journal Political Studies found that as party systems polarise economically, the negative impact of income inequality on turnout is reduced, until it is eliminated. Building on this research, I have now investigated the income groups most affected in the relationship.

I found that higher income inequality increases the saliency of redistribution for rich and poor alike. It is low-income earners, however, who have the most to lose relatively, and who are then mobilised to the largest extent via greater economic policy choice.

low-income earners have the most to lose relatively, and are mobilised to the largest extent via greater economic policy choice

My findings magnify the negative impacts income inequality can exert on political behaviour. They also reveal that policy offerings are a key moderating mechanism in the relationship.

The findings point to a distinct inequality in representation throughout the West. Despite the egalitarian principles of democracy, political parties are largely under-representing the poorest citizens. By not providing effective economic policy options for low-income earners, parties are dampening turnout and increasing political inequality.

This is likely perpetuating a vicious cycle of marginalisation that depresses the participation of lower income groups. In turn, this leads to even greater representation of the wealthy and less public effort to combat inequality.

These effects can also increase the pool of disenfranchised voters. The result is that an attractive prospective reservoir of support forms, from which populists and authoritarians – especially on the radical right – are free to draw.

This blog is based on Matt's recent Party Politics article Inequality, policy polarization and the income gap in turnout