On Sunday 9 June 2024, Bulgaria went to the polls for the sixth parliamentary elections in three years. Bulgaria's political crisis, however, is far from over, writes Ivaylo Dinev

Bulgaria has endured longstanding entrenched corruption, decades of mass protests, and a shrinking population. Boyko Borissov and Delyan Peevski, two faces of the Balkan country's captured state, symbolise the deep-rooted collusion between Bulgaria's media, politicians, and oligarchs. Astonishingly, these two seem poised to govern Bulgaria once again, after securing 41.8% of the vote.

According to official results, Borissov’s GERB won 24.7% of the vote; Peevski’s DPS 17.1%

According to Assen Vassilev, co-chair of the reformist party We Continue the Change, Peevski has set his long-term sights on becoming Prime Minister. Borissov, meanwhile, eyes retirement as President. This might sound unthinkable for many Bulgarians and observers, but the rising political fragmentation and public disillusionment (the latest elections had the lowest-ever voter turnout) could give these parties the opportunity they need. According to official results, Borissov’s GERB, a personalist centre-right party, won 24.7% of the vote; Peevski’s DPS, 17.1%. This resulted in 115 mandates. To form a cabinet, parties need at least 121 votes from the 240-seat parliament.

| Party | Profile | National elections % | EU elections % | Seats in national parliament | Seat change |

| Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) | Centre-right | 24.7 | 23.6 | 68 | -1 |

| Movement for Rights and Freedom (DPS) | Liberalist / Turkish minority | 17.1 | 14.7 | 47 | 11 |

| We Continue the Change-Democratic Bulgaria (PPDB) | Liberalist | 14.3 | 14.5 | 39 | -25 |

| Revival (V) | National populist | 13.8 | 14.0 | 38 | 1 |

| Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) | Centre-left | 7.1 | 7.0 | 19 | -4 |

| There is Such a People (ITN) | Populist | 6.0 | 6.0 | 16 | 5 |

| Greatness (VE) | National populist | 4.7 | 4.1 | 13 | new |

Sixty-four year-old Boyko Borissov, a former security firm boss and three-time prime minister, has a notorious history. He stands accused by many, including a former American ambassador, of mafia ties, widespread use of intimidation, and corruption. Borissov’s list of scandals is long enough to provide a script for a Netflix crime series. Despite these allegations, he remains a key ally of the European People’s Party.

Borissov stands accused of mafia ties, widespread use of intimidation, and corruption

Delyan Peevski, 43, recently elected co-leader of the DPS party, is a media mogul sanctioned under the Magnitsky Act in the UK and USA for corruption. Yet his party is influential in the liberal alliance Renew Europe, and he is a loyal supporter of EU foreign policy. DPS claims to represent ethnic Turks and Romani voters — the groups with the highest poverty rates in Bulgaria.

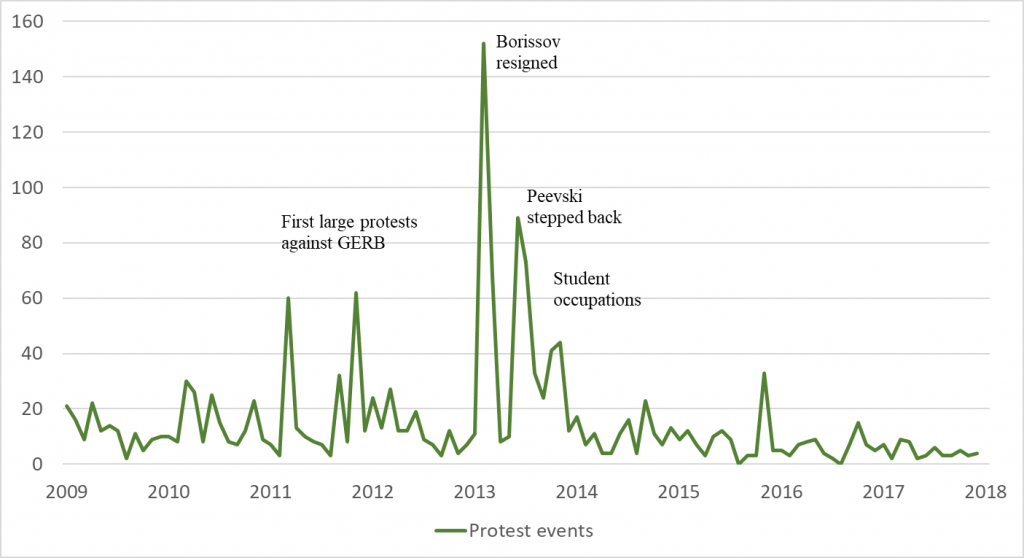

Bulgarians demanded Borissov's resignation in February 2013, at the end of his first term, which ran from 2009—2013. More than 160,000 people in over 35 cities protested against poverty and the corrupt political establishment. Tragically, several Bulgarians even resorted to self-immolation. These were the first mass protests in Bulgaria since the 1990s, and they led to Borissov's resignation. Bulgarians called for his resignation once again in 2020 during Borissov's third GERB government (2017—2021). Hundreds of thousands took to the streets in anti-mafia protests.

In June 2013, Peevski's election as president of the State Agency for National Security sparked immediate outrage. Tens of thousands gathered outside government headquarters in Sofia only two hours after the vote, chanting 'Mafia!' and 'Resign!'. Four months later, students staged sit-ins at Sofia University and 19 other universities across Bulgaria, appalled by the cynicism of the country’s political class. These two protest waves became the most sustained protest movement in the recent East-Central European history. They persisted for an entire year, and succeeded in mobilising diaspora protests rallies in most Western capitals.

Following the 2020 protests, the opposition parties to GERB and DPS did not collectively hold enough mandates to form a government. It took three parliamentary elections before the reform-oriented We Continue the Change (PP), Democratic Bulgaria (DB), the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), and There is Such a People (ITN) secured the necessary mandates and formed a fragile cabinet. This government lasted only six months, however, because ITN withdrew from the coalition.

After the fifth parliamentary elections in November 2023, the reformist PP-DB coalition, which had been the fiercest opponent of the GERB model, agreed with its rivals GERB and DPS on two policies: a government with Euro-Atlantic orientation and a reform of the Constitution. Thus, everything that hundreds of thousands of people had protested about for the last decade — the fight against corruption and the influence of the oligarchy — was sidelined. Several splinters and new protest parties have since emerged. This has simply led to yet further fragmentation of the vote.

Despite the large-scale protests against GERB and DPS, senior European politicians have continued to publicly support the two parties, which have firmly aligned with two of the major European political groups. Bulgaria has thus become a stabilitocracy: a regime with considerable democratic shortcomings, but which enjoys some external legitimacy.

The historically positive view of the European Union in Bulgaria is gradually shifting. Recent data shows that only 52% of Bulgarians trust the EU, a significant change from just a few years ago. In the recent European Parliament elections, national populist parties gained unprecedented success. Along with Revival’s 13.8% support, the newcomer Velichie (Greatness), entered Parliament with 4.7% of the vote. Together with the soft-Eurosceptic BSP, ITN, and several smaller parties below the threshold, the total weight of the Eurosceptic bloc is about 37%.

The Bulgarian political crisis is far from over. The reformist parties would benefit from remaining in opposition, because another compromise with GERB and DPS could appear total capitulation. This would force GERB and DPS to seek new partners, likely triggering discontent similar to the 2013—2020 period.

The reformist parties would benefit from remaining in opposition, because another compromise with GERB and DPS could appear total capitulation

During the past decade, it has become clear that only protests can crack the captured state. When elections fail to secure an outcome, the only other move in democratic systems is to protest. Or, sadly, to 'exit'. This is the decision that the two million-plus Bulgarians who have left the country since 1989 have chosen to make.