Regime classifications are in dire need of better 'adjectives'. Ed Dolan introduces a new typology focused on rule compliance, which matters greatly in democracies and in authoritarian regimes. China is the non-compliant authoritarian regime exception that shows why

In the first post of this series, Hager Ali laments the absence of a detailed typology for autocratic regimes. To move the discipline forward, I bring a new variable into play: the degree of compliance with a set of rules of good government that are equally important for autocracies and democracies.

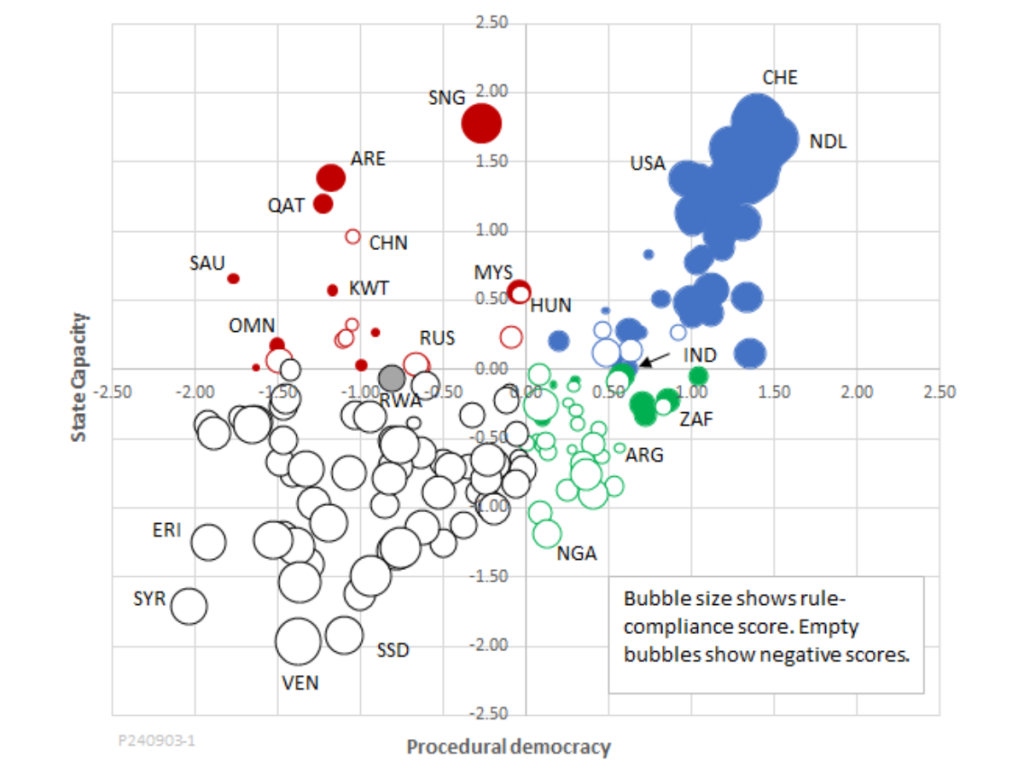

Combining rule compliance with democracy and state capacity creates an eight-way classification of regime types. My recent research sheds new light on why it is that even though most authoritarian regimes are weak, a handful of 'institutional autocracies' like Singapore and the UAE still manage to achieve high state capacity. It also helps explain why, even with free and fair elections, democracies like Brazil and Mexico fail to achieve high state capacity. Finally, the new framework provides key insights into the special case of China.

My research focuses on compliance with four types of rules:

This set of rules is relevant across all regime types. The list purposely omits rules governing human rights and personal freedoms, which tend to be weak in non-democratic states.

I use the variable democracy in a procedural sense that focuses narrowly on free and fair elections.

For state capacity, I use an index that averages administrative, security, and fiscal components. I treat state capacity as the ability of a government to achieve its goals regardless of whether an outsider approves or disapproves of their content.

The table below provides an overview of this, with definitions, average scores, and examples of the eight regime types. The graphic below it represents the three variables as Z-scores that are positive if higher and negative if lower than the global mean. For details on data, sources, and definitions, see my longer research paper.

| Regime type | Number | Average state capacity | Average rule compliance | Average democracy | Average human rights | Examples |

| Liberal or partly liberal democracy | 48 | 1.07 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.14 | US, UK, Scandinavia, Japan |

| Strong non-compliant democracy | 4 | 0.20 | -0.39 | 0.63 | 0.35 | Albania, Paraguay |

| Weak compliant democracy | 10 | -0.20 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.52 | South Africa, Jamaica, Armenia |

| Weak non-compliant democracy | 26 | -0.52 | -0.34 | 0.31 | 0.21 | Brazil, Mexico, Kenya, Nigeria |

| Institutional autocracy | 10 | 0.66 | 0.44 | -1.07 | -0.98 | Singapore, UAE, Qatar, Malaysia |

| Strong non-compliant autocracy | 9 | 0.29 | -0.32 | -0.80 | -0.82 | China, Russia, Hungary, Vietnam |

| Weak compliant autocracy | 1 | -0.06 | 0.61 | -0.81 | -0.64 | Rwanda |

| Weak non-compliant autocracy | 58 | -0.82 | -0.90 | -0.91 | -0.84 | Pakistan, Turkey, Venezuela |

The table shows that strong governments follow the rules. Earlier in this series, Matthijs Bogaards suggested that we can consider autocratic regimes mirror images of corresponding democratic types, and this pattern is clearly visible in the graphic. On both sides of the central vertical axis, the governments with the highest state capacity are rule-followers.

This is no surprise for democracies. Theorists such as Kevin Vallier have long emphasised that liberal democracy is not just a matter of free and fair elections, but also of constitutional limits, rules for free markets, and rules that protect human rights. Nearly all the countries represented as blue bubbles are liberal democracies in that sense.

In some institutionalised countries, executive leadership is less constrained and more strongly personalised. In others, leadership is more institutionalised

On the non-democratic side, the highest-capacity states are again rule-compliant (solid red bubbles). That is where my new adjective comes in. I could call these ten regimes 'compliant autocracies', but perhaps the term institutional autocracies is better, since rule-compliance implies strong institutions such as law-based courts and competent bureaucracies.

It is worth noting that in some countries within this group, executive leadership is less constrained and more strongly personalised, while in others, leadership is more institutionalised. Although all of them have positive scores for rule compliance as averaged across the four rule categories, some have negative scores for executive constraints. This may be a marker for more personalised leadership. Singapore and the UAE illustrate the more institutional pattern, while leadership in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan is more personalised.

Finally, although the institutional autocracies have high average scores for rule of law, all of them score below the global average on human rights. Seemingly, their laws, even when they appear unjust to outsiders, are enforced in a way that is not entirely arbitrary.

A second major finding is that democracy and state capacity are positively correlated, but only for countries on the right-hand side of the chart. Within that group, multivariate analysis shows that procedural democracy and rule compliance are of about equal importance as determinants of strong state capacity.

Adding token gestures toward democracy in states that are deeply autocratic to begin with has no real payoff for state capacity

In contrast, among autocracies, rule compliance has an even stronger effect on state capacity. However, democracy has no statistically significant effect. It appears that adding token gestures toward democracy in states that are deeply autocratic to begin with has no real payoff for state capacity, whereas even modest rule compliance improves governance among the weak states in the lower-left quadrant.

And what about China? Is it the exception that proves an autocratic rule-breaker can achieve high state capacity? A closer look gives a more nuanced picture. Much of former Communist leader Deng Xiaoping’s transformation of China after Chairman Mao consisted of rule-based reforms, including term limits, control of corruption, and creation of market institutions. The Deng period coincided with strong gains in state capacity. However, as growth has slowed under current paramount leader Xi Jinping, China has moved backwards on rule compliance.

As China's growth has slowed under Xi Jinping, the country has moved backwards on rule compliance

As part of my research, I constructed approximate retrospective time series for Chinese rule compliance, using Legatum Institute data. The series showed peak scores for rule of law in 2012, executive constraints in 2016, market institutions in 2021, and integrity in 2022. If China had maintained its peak performance in each of these, its overall score for rule compliance would now be slightly positive. China would then appear in the graphic as a solid red bubble close to Qatar.

Rule-compliance, then, is a powerful adjective for understanding both democracies and autocracies. Even the special case of China is not a clear exception.