Internationally hailed as a breakthrough, Armenia’s US-brokered peace with Azerbaijan has come at steep domestic cost. Logan Liut explores how Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s foreign policy pivot triggered a rupture between the state and the influential Armenian Apostolic Church — threatening a vital source of Armenian soft power

On 8 August 2025, a US-brokered agreement mediated by President Donald Trump brought an end to decades of conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan; a step towards the normalisation of relations. The price of this peace, however, has been high for Armenia’s government. Prime Minister Pashinyan has defied fierce domestic opposition — especially from the Armenian Apostolic Church — to get there.

The deal has not been celebrated inside Armenia as much as it has been internationally. At home, the agreement lands amid an increasingly bitter confrontation between Pashinyan’s government and Church leader Catholicos Karekin II. The Church is a pillar of Armenian national identity; an effective conduit for advancing the interests of a small, resource-constrained homeland, especially in the diaspora.

Independent from the state, senior clerics of the Armenian Apostolic Church have vehemently opposed Armenian concessions to resolve regional tensions

The Church remains independent from the state, however, and senior clerics have vehemently opposed Armenian concessions to resolve regional tensions, especially concerning ethnic Armenian self-determination in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. So, while the recent agreement may have ended one of the post-Soviet world’s most protracted conflicts, it may also have cost the Armenian state its valuable — and effective — ecclesiastical instrument of foreign policy.

The growing chasm between church and state in Armenia is, at its heart, a divide over where Armenia should align itself internationally. Russia, Armenia’s traditional security partner, failed to meaningfully intervene in successive conflicts with Azerbaijan in 2020 and 2023. Since then, Pashinyan has gradually but decisively pivoted Armenian foreign policy toward the West. His aim is to reduce Armenia’s reliance on an unreliable Russian security umbrella, while eventually seeking to negotiate an end to long-standing conflict with neighbouring Azerbaijan.

The Armenian Apostolic Church, sharing a common Orthodox identity with Russia, is socially and politically closer to Moscow. As a result, it enjoyed warmer relations with the more Russia-aligned establishment predating the Velvet Revolution of 2018 which helped bring Pashinyan to power.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan's aim is to reduce Armenia's reliance on Russian security, but the Apostolic Church is socially and politically closer to Moscow

The seeds of today’s rift were, however, sown amid the loss of ethnic Armenian control of the Nagorno-Karabakh region in 2023. Many Armenians — especially in the diaspora — see the fall of the Republic of Artsakh and the subsequent end of an Armenian presence in the region as a profound national tragedy.

Clerics have taken active roles in anti-government protests emerging from this conflict, aligning with opposition parties closer to Moscow in calling for Pashinyan’s ouster. Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan has spearheaded a wider Sacred Struggle movement — growing out of the 'Tavush for the Motherland' protests he led in 2024, and supported by Catholicos Karekin II — demanding that Pashinyan resign. Archbishop Galstanyan has even offered himself as a possible interim prime minister.

Pashinyan, unsurprisingly, has come to view the Church’s interventions in politics as a direct threat to the state. This tension has devolved into a bitter personal feud between Pashinyan and Karekin II. Archbishop Galstanyan, meanwhile, finds himself incarcerated, as Armenian authorities claim to have foiled a coup plot involving him and multiple other people connected to his movement.

Prime Minister Pashinyan’s government is considerably weakened today. It is commendable that Pashinyan has pivoted away from Armenia’s dead-end foreign-policy strategy and found a way to make peace in a tough neighbourhood. Yet, while this peace deal is monumental for regional stability, Pashinyan has made deeply contentious decisions — especially in the diaspora — to get to this point, from officially accepting full Azerbaijani sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh to making a road link on Armenian soil available for development between mainland Azerbaijan and its sizeable Nakhchivan enclave.

The recent peace deal is monumental for regional stability, but Pashinyan has made some deeply contentious decisions along the way, including officially accepting full Azerbaijani sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh

This clash between church and state, however, isn’t just a domestic spat. It now risks seriously jeopardising Armenia’s already limited ability to project power on the international stage. There are real concerns for Armenian soft power and its wider foreign policy. As a small state, Armenia has often relied on its diaspora as a diplomatic tool — by some estimates, more than 70% of people of Armenian origin live outside Armenia. Many of those communities connect to the homeland through the cross-border networks of the Apostolic Church. A weakened — or even destroyed — bridge between Church and state risks isolating Yerevan from much of its most reliable international support network at a time of unprecedented vulnerability and change.

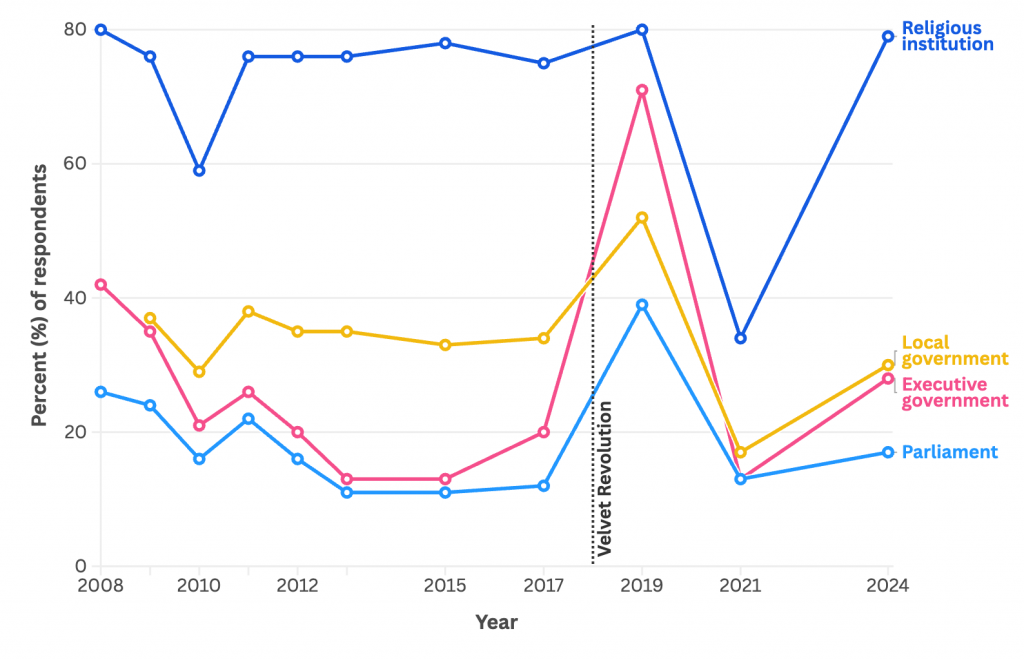

After the Velvet Revolution of 2018, Pashinyan enjoyed a honeymoon period. Despite this, he has never enjoyed a level of public trust that surpassed trust in religious institutions. Data from the Caucasus Research Resource Center indicates that confidence in religious institutions has recovered to its high pre-Revolution levels. The government’s share of public trust, meanwhile, has shrunk to a level comparable with Armenia’s pre-2018 government.

Open hostility between church and state in Armenia is untenable — and perilous in the long term. Pashinyan has recently proposed forcibly changing Church leadership. This would violate the Apostolic Church’s institutional independence and is not a serious option. Neither are senior clerics’ attempts to replace Pashinyan’s government. Indeed, continued overt church alignment with the political opposition risks jeopardising the church's ability to remain an important unifying institution for the Armenian people.

Without some resolution of this conflict soon, Pashinyan will continue to wound his already tenuous personal legitimacy at home, and permanent damage to Armenia's ability to advance its interests abroad is a real possibility.

Whether Armenia’s government can reconcile with one of its principal soft-power institutions — the Armenian Apostolic Church — is key to determining whether this new era of peace translates into stability and durable security for the Armenian people in the heart of the South Caucasus.

He seeks to get the church to fight itself. Is he trying to create a "state sanctioned church?" Not sure if this will work. Not sure if he can control the outcome. At least he can count on Turkish interests to just sit back...and Trump? "Don't disrupt my Iranian bypass route!"