On 24 December 2025, Algeria passed a law recognising French colonisation as a state crime, and calling for restitution and reparations. The law is primarily domestic and symbolic. But Morgiane Noel argues that it signals a significant postcolonial shift which could influence African politics, Europe–Africa relations, and discussions of historical justice in international law

Algeria's recently enacted law also prescribes penalties for Algerian citizens who glorify or justify colonialism. Punishment can involve the loss of civil rights and five to ten years of imprisonment. In addition, the new law addresses the question of the Harkis, Algerian auxiliaries of the French army, who were colonial forces.

The law’s significance extends beyond a contentious bilateral relationship between France and Algeria. Most African former colonies have confined their recognition of colonial violence to a symbolic or depoliticised approach. Algeria has taken a more assertive stance, legally recognising colonisation, a system of oppression, as a state crime. In doing so, it explicitly departs from the principle of non-retroactivity in international criminal law.

Algeria's new law asserts that its government can indeed judge colonial practices retroactively, given the severe human rights violations they entailed

Non-retroactivity in this context means that the government cannot criminally prosecute for conduct if the law did not define that conduct as a crime at the time it occurred. Algeria is challenging this principle. The law asserts that it can indeed judge colonial practices retroactively, given their systematic nature and the severe human rights violations they entailed. Algeria's legal move aims to contest colonial legacies, reshape historical narratives, and reassert political agency in post-colonial relations.

The concept of a crime against humanity was only formally recognised in August 1945, following the Nuremberg trials. Colonisation predates the establishment of this legal framework by a significant period. Therefore, by highlighting the scale, length, and widespread violence of colonial rule, countries such as Algeria challenge this reasoning. Algeria strongly advocates for an interpretation of international law that emphasises justice and collective memory over rigid legal timelines.

By setting aside this temporal barrier, the Algerian law argues that the scale, violence, and systemic nature of colonial domination justify moral and political criminalisation. It also addresses the intergenerational consequences of colonisation, including persistent inequalities, economic dependence, social divisions, and inherited trauma.

This law aligns with Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), a body of scholarship that critiques how international law has historically served colonial powers. Indeed, it maintains that the law continues to marginalise formerly colonised states, challenging the ethnocentric and Eurocentric underpinnings of the international law framework. TWAIL also acknowledges not only specific events but also the continuous nature of colonisation. Franz Fanon’s theories reinforced the argument that colonisation is built into the system itself, leaving a legacy that stretches across time and space.

The new law addresses the intergenerational consequences of colonisation, including persistent inequalities, economic dependence, social divisions, and inherited trauma

Algeria's new legislation may also strengthen legal and historical Pan-Africanism. Pan-Africanism began as a social movement in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It encourages unity, solidarity, and self-determination among African people, in Africa and throughout the global African diaspora. The movement has often been impeded by fragmented memory resulting from diverse colonial experiences. Structural dependence of postcolonial states on former colonial powers has also hampered their progress. However, the introduction of a unifying legal approach to colonisation by Algeria can facilitate the development of a shared memory base capable of transcending linguistic, imperial, and regional divisions.

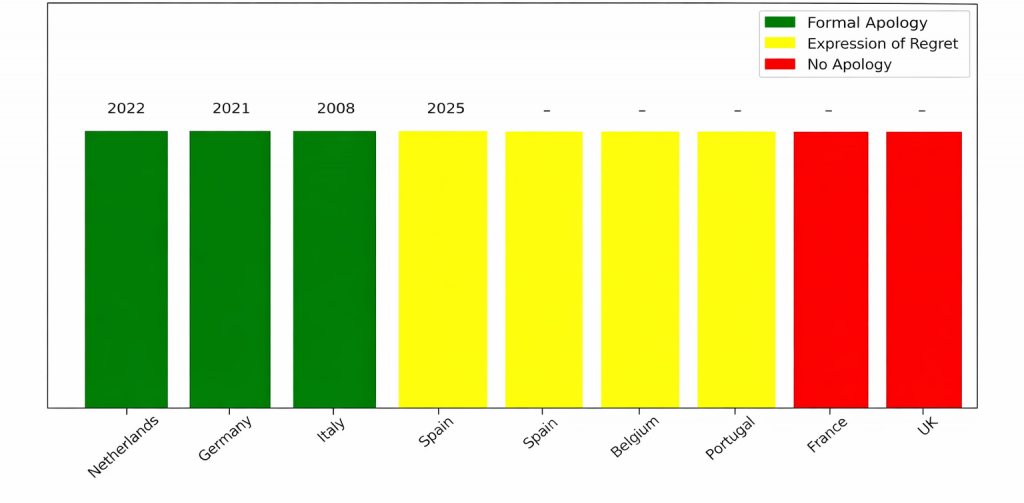

The new legislation operates within its domestic legal framework. Yet it prompts a critical examination of Europe’s role as a proponent of human rights and universal values. Most African countries achieved independence between the 1950s and 1980s, and some former colonial powers have acknowledged past actions. These include Germany, which pledged €1.1 billion in aid to Namibia for the Herero and Nama genocide, yet did not accept full legal responsibility or provide direct compensation to victims’ descendants. This was a decision criticised by the Windhoek government and local communities.

Substantive reparations remain rare. Only a few countries have issued formal apologies accompanied by financial compensation. Algeria's demand for reparations sets a significant precedent and highlights the nation's assertive position within restitution discussions and broader international debates.

Algerian law defines French colonisation as a crime against the state. Public and political discourse frequently describe it as a crime against humanity. But it is challenging to subsume colonial systemic violence within existing categories of international criminal law. To recognise colonisation as a crime against humanity, we must see it as an ongoing system of domination, rather than merely a collection of isolated human rights violations.

Across the world, however, colonial experiences varied by region, time period, and type of control, making it difficult to use a single legal definition. Some acts, like massacres, forced displacement, or summary executions, are already recognised as crimes against humanity. Their classification remains a matter for debate. These uncertainties help explain why colonial violence is still caught between legal recognition and political condemnation.

It is challenging to subsume colonial systemic violence within existing categories of international criminal law. To do so, we must see it as an ongoing system of domination, rather than merely a collection of isolated human rights violations

This analysis advances the argument by defining colonisation as a systemic crime that involves serious violations, committed repeatedly by political, economic, or social systems. There is precedent for this approach: apartheid was once a legal domestic policy, later condemned politically and morally, and ultimately recognised as a crime against humanity. The process of reclassifying apartheid from a domestic policy to an international crime took time. It occurred through ongoing international condemnation and sanctions, internal resistance within South Africa, the gradual repeal of apartheid laws, and eventual recognition by the United Nations.

Today, colonisation remains a systemic injustice with real political and economic effects. This highlights the need for recognition, even if there is no formal support in international law. Algeria's new law could set an example. It shows that states can admit to colonial crimes without risking their stability, and that taking responsibility for history can strengthen political legitimacy without automatically leading to large-scale reparations.