The war in Sudan has passed the five-month mark, and peace efforts seem to have plateaued. Breaking down Sudan’s political system and transition since 2019, Hager Ali explains how defective interim governance enabled the violent power struggle between the country’s largest armed forces. She argues that past political systems could still undermine present peace efforts

Sudan’s power struggle between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) under Abdelfattah al-Burhan’s command, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, devolved into a war of attrition. Neither force has thus far managed to gain decisive tactical advantages in Khartoum.

Since the beginning of the conflict, domestic and international actors have initiated multiple decentralised peace processes. These efforts, however, have often been suspended over ceasefire violations. Most recently, Al-Burhan convened a cabinet meeting for the first time since April. Dagalo, meanwhile, posted a 10-point plan detailing the RSF’s vision of a resolution.

Stopping the war in Sudan is about more than laying down arms. The country needs a political system that can guide and cement its exit from violence

Through the military and political stalemate, the people of Sudan face the monumental task of finding an exit strategy. A planned integration of the RSF into the SAF triggered the initial escalation of hostilities between Al-Burhan and Dagalo. However, it was Sudan’s dysfunctional political system between the October 2021 coup and April 2023 which set the stage for this conflict. Stopping the war between the SAF and RSF in Sudan will require more than merely laying down arms. Equally important is building a political system that can guide and cement the exit from violence.

Engineering a political system is risky. Interim regimes are a means to an end in which appointed political actors conduct a transition with preliminary institutions. Interim stakeholders prescribe how to set the new permanent rules, how to form a new electoral system, and who can vote or run in the first elections. A country’s last functional political system is typically the point of departure. Going forward, the country will either replicate or outlaw attributes from it. In post-conflict settings, interim governance should, ideally, terminate war. Conflict parties can make their ending of violence conditional on the future political system.

Policymakers underestimate how essential is the formalised 'unmaking' of previous institutions, even after state collapse

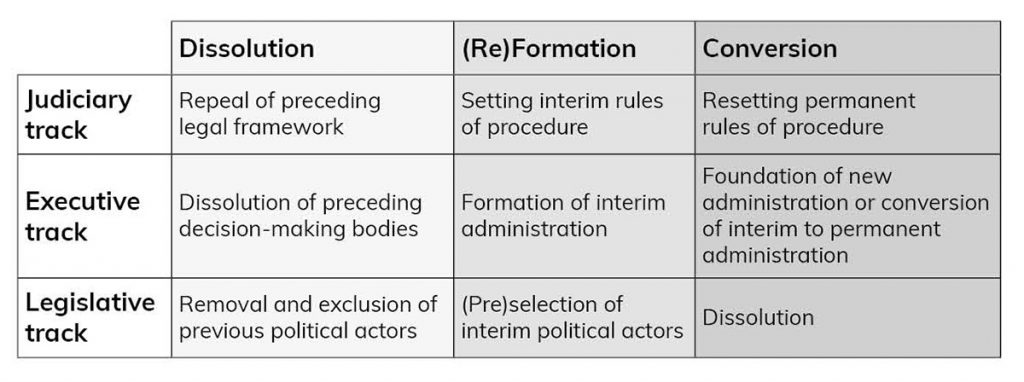

Exiting long-standing authoritarian regimes or conflicts introduces additional steps into interim governance. The table below disaggregates these steps into three stages and three tracks. In 'Dissolution', former political systems come undone through a repeal of preceding legal frameworks, dissolution of executive decision-making bodies, and the exclusion of previous stakeholders. During '(Re-)Formation', central political actors are appointed to set interim rules of procedure. '(Re-)Formation' prepares the structural, personnel, and legal set-up for the 'Conversion' into a permanent regime, in which elections determine the first generation of incumbents and legislators.

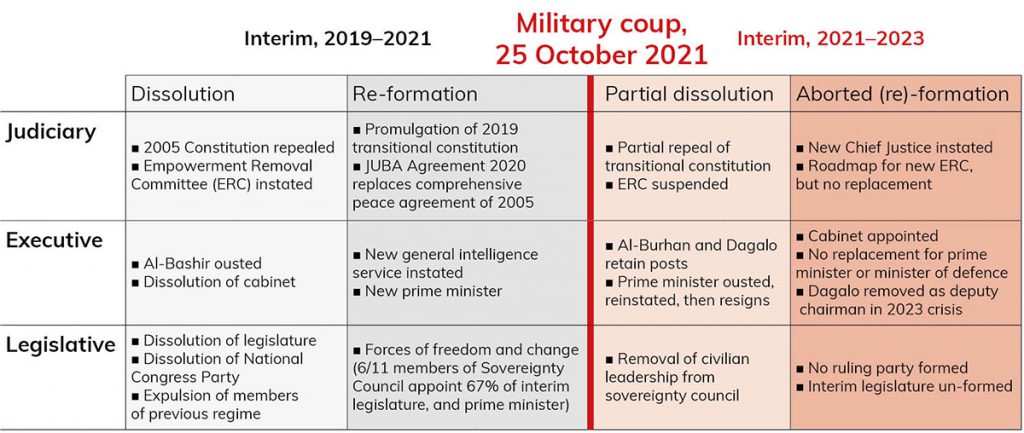

Policymakers, unfortunately, tend to underestimate how essential is the formalised ‘unmaking’ of previous institutions, even after state collapse. They also underestimate the devastating effects on political stability when something disrupts this process. Al-Burhan’s 2021 coup trapped Sudan’s political system between Dissolution and Formation.

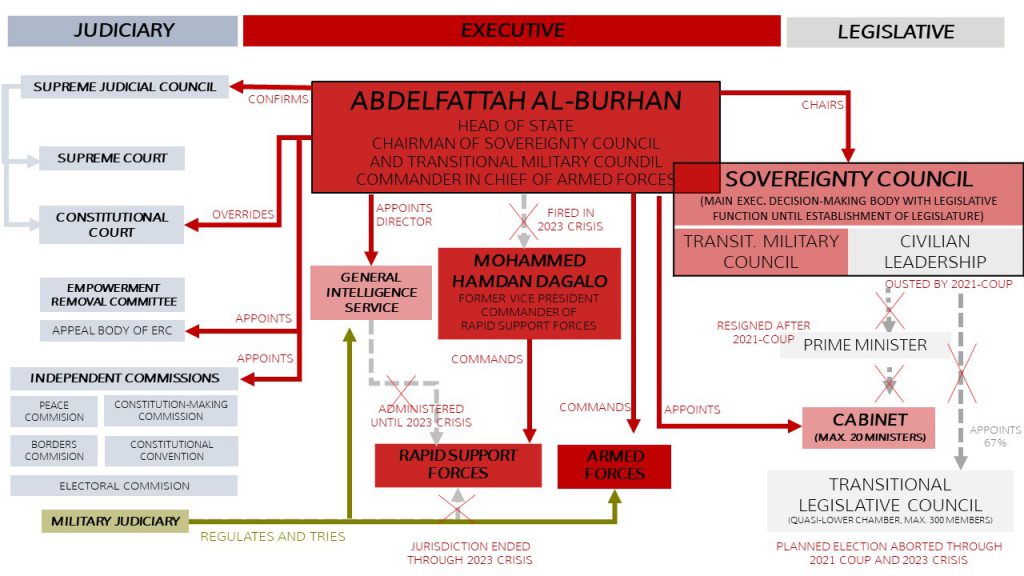

From 2019 to 2023, the separation of powers was generally murky. The Sovereignty Council (SC), co-chaired by Al-Burhan and Dagalo, was the main executive decision-making body, but its legislative function made it into a quasi-Senate. From 2019 until the 2021 coup, the SC had five military members in a Transitional Military Council, and six civilian members. Once formed, the Transitional Legislative Council would function like a lower chamber. The civilian leadership appointed the Prime Minister who would in turn appoint the cabinet. Dagalo and the General Intelligence Service oversaw the RSF, while the Armed Forces were subjugated to the Sovereignty Council and Al-Burhan.

At that time, the dissolution of Al-Bashir’s regime and the military-to-civilian handoff were central priorities. Between 2019 and 2020, Al-Bashir’s former ruling party was dissolved, the 2005 constitution replaced by the 2019 transitional constitutional declaration, and members of the previous regime purged. The new SC was sworn in as general elections were set for July 2023. On the judiciary track, Al-Burhan had appointed a new chief justice, and promulgated a new interim constitution. He also approved the new Empowerment Removal Committee to formally dismantle Al-Bashir’s regime. Nearing the handoff to civilians outlined in the transitional timeline, the SC was in place, but not fully operational.

The graphic below visualises how an overextended executive steamrolled both the judiciary and legislature. After the 2021 coup, remnants of Al-Bashir’s regime were too far gone to be brought back quickly. And the democratisation process had not yet yielded operational institutions, leaving Al-Burhan and Dagalo to govern with few institutional intermediaries and no ruling party. Constitutional reform after the coup largely retained the interim government’s structure but altered executive authority over appointments in other branches.

Not all vacancies were filled, worsening the problem. Al-Burhan had appointed a 15-member cabinet, but no new Prime Minister after Abdullah Hamdok’s resignation in January 2022. Nor did he appoint a new minister of defence. The Transitional Legislative Council remained unformed, which left the remainder of the regime without a formalised arena to deliberate policy matters – including the planned integration of the RSF into the SAF. In May 2023, Dagalo was fired from his post which unravels how the RSF was tied into the executive.

Sudan’s 2021 post-coup government can still sabotage peace if future interim governments replicate its structural attributes

War alone does not erase institutional legacies; it only suspends them until they are formally dismantled. Sudan’s 2021 post-coup government can still sabotage peace if future interim governments replicate its structural attributes. Al-Burhan’s system actively undermines democratisation because it is incompatible with anything other than a military head of state. Without a legislature, a ruling coalition has no formalised political arena to pass legislation and resolve internal conflicts. And without a functioning judiciary, there are no formal guarantees that power-sharing arrangements will endure.

Any future political system needs to strengthen legislature and judiciary against a traditionally strong but overstretched executive authority. As dangerous as the breakdown of Sudan’s security apparatus has been throughout this conflict, it is also a chance for meaningful reform.