Fathali M. Moghaddam puts forward a picture of 'actualised democracy' aimed at the equal participation of every person in all public decision-making. For it to succeed, today’s citizens need upskilling into 'democratic citizens'

Actualised democracy represents an ideal. It describes a society in which people enjoy '…full, informed, equal participation in wide aspects of political, economic, and cultural decision-making independent of financial investment and resources'.

Of course, actualised democracy does not exist – yet. And this is because we have not yet achieved the psychological portrait of the democratic citizen in a demographically broad or especially multiracial sense.

The primary goal of my research has been to stimulate debate about what the characteristics of an actualised democracy could be. It also aims to understand the nature of the democratic citizens it requires to both be manifested and upheld.

We have a very long way to go, however. All societies began as dictatorships and the path to actualised democracy is therefore uncertain and slow. Think of a continuum with absolute dictatorship at one end and actualised democracy at the other. All societies lie somewhere between these two extremes:

The foundation of actualised democracy is the democratic citizen. In this regard, supporters of democracy face two central challenges. First, they must identify the psychological characteristics of democratic citizens. Second, they must develop education systems for training democratic citizens.

In modern times, John Dewey (1859–1952) and others have broadly discussed the challenges of educating for democracy. More recently, critics have pointed to the failure of the US education system to develop independent thinkers capable of fully participating in a democracy. For example, in Excellent Sheep, William Deresiewicz argues that even the American elite suffer ‘miseducation’.

In an ideal society, citizens would enjoy equal participation in all aspects of public decision-making, independent of financial resources

I took on the more specific challenge of identifying the psychological characteristics we need to nurture in individuals, as part of their personalities, in order to produce democratic citizens. Again, my goal is to put forward what I see to be an ideal, to stimulate and channel debate.

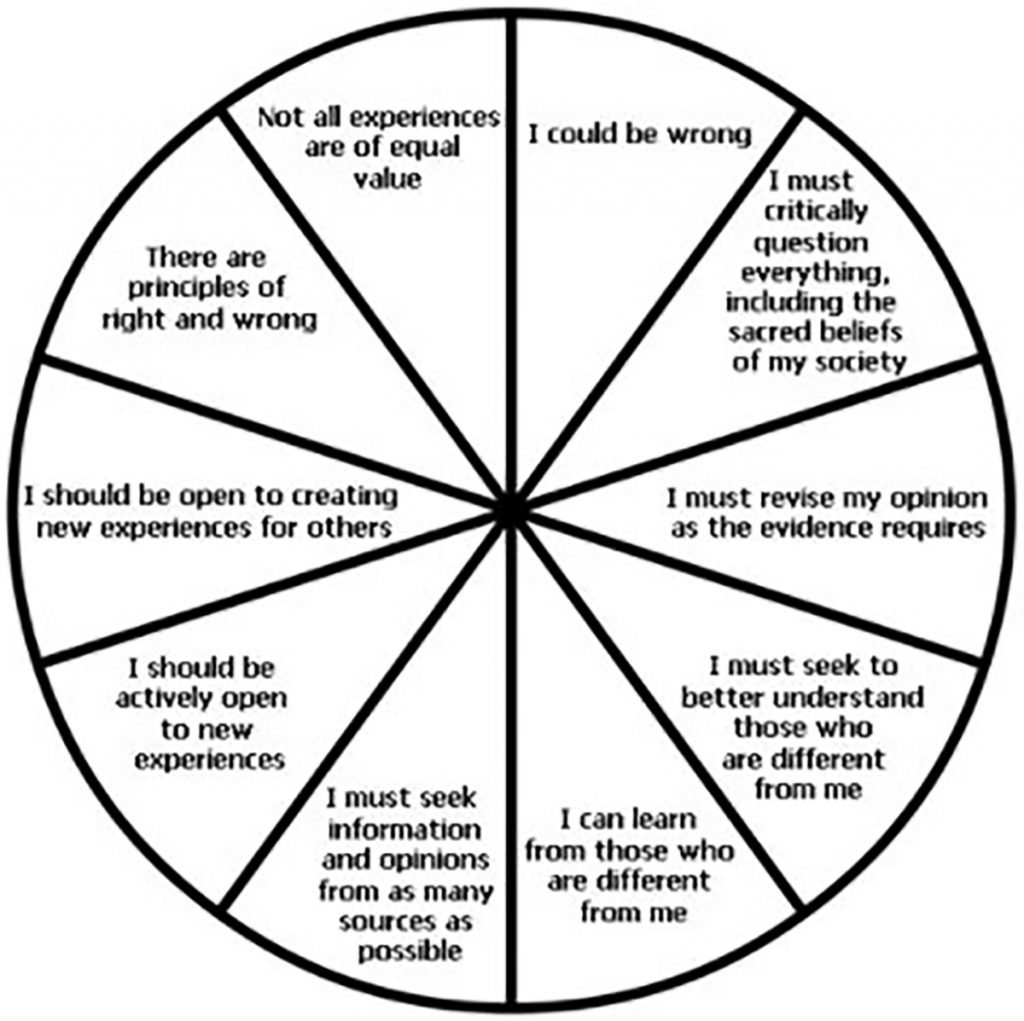

I identified the above ten psychological characteristics as essential for democratic citizenship. The first of these is perhaps the most challenging. It is the ability to begin any interaction – formal discussion, informal dialogue, or casual get-together – with the acknowledgement that 'I could be wrong'.

The most challenging characteristic essential to democratic citizenship is the ability to begin any interaction with the acknowledgment that 'I could be wrong'

Of course, this seemingly simple starting point is actually really challenging. Those already strongly committed to a particular worldview will, naturally, struggle to accept that they could be wrong. This view of the world could be linked to a political ideology or a religion or some other worldview. Individuals with strong authoritarian, dogmatic, and related psychological traits will also refuse to accept such a starting point for themselves.

The next characteristic is 'I must critically question everything, including the sacred beliefs of my society'. The third is 'I must revise my opinion as evidence requires'. These two emphasise the open-minded and evidence-based outlook of the democratic citizen. The requirement that the democratic citizen also question even the sacred beliefs of her society calls for the ability and strength to resist societal and authoritative pressures to conform and to obey.

The next three characteristics have to do with seeking information from diverse sources. They are: 'I must seek to understand those who are different from me', 'I can learn from those who are different from me', and 'I must seek information and opinions from as many sources as possible'. These characteristics move the democratic citizen to become more open to and informed about diversity in worldviews. It is an antidote to bigotry.

This tendency is strengthened by developing one's openness to new experiences, and to sharing experiences with dissimilar others. Characteristics seven and eight, therefore, are: 'I should be actively open to new experiences' and 'I should be open to creating new experiences for others'.

But these first eight characteristics could lead individuals into the quagmire of relativism. Here, all opinions and experiences are of equal value. At the absurd level, this could lead to views such as: 'Ferdowsi and Shakespeare have no more literary value than a telephone book'.

A universalist perspective, which accepts there are principles of right and wrong, leads to the rejection of dictatorship, and support for democracy, for all humans

In order to avoid such relativism, the final two characteristics of the democratic citizen are universalist. This perspective accepts the statements: 'there are principles of right and wrong', and 'not all experiences are of equal value'. It is this universalist perspective that, for example, leads to support for the United National Declaration of Human Rights, the rejection of dictatorship, and the support for democracy – for all humans.

Actualised democracy is an ideal in the tradition of Plato’s Republic and Thomas More’s Utopia. As Plato and More do in their respective works, I too have put forward an ideal of the characteristics that the democratic citizen should embody.

And I do this to argue that a society composed of such edified or morally oriented individuals holds the prospect of peacefully establishing laws and the nature of their application.

Equally so, I aver that such a society of democratic citizens is what is minimally required for an actualised democracy – or a political system in which everyone can participate equally on any public issue, institution or matter – to succeed.

No.82 in a Loop thread on the science of democracy. Look out for the 🦋 to read more in our series