Since the 1980s, electoral autocracy has been considered the most common form of dictatorship. Yet, as Adrián del Río shows, little is known about what this regime is and how we can recognise it. In fact, there is only a 34% probability that famous datasets agree on identifying such a regime

Giovanni Sartori warned political scientists of the dangerous proliferation of 'cat-dogs' – concepts that emerge from lumping 'cats and dogs' together because they share some attributes. Of course, such creatures do not exist.

The popular term electoral autocracy is one of these cat-dog concepts. It treats different 'hybrid' autocracies as if they were the same because they hold multiparty elections but fail to guarantee minimum 'democratic standards'.

Where empirical reality is fuzzy, applying somewhat loose concepts can generate high analytical costs for decision-makers and researchers. For example, one might risk comparing 'real' electoral autocracies with the most minimalist democracies.

They might share some characteristics. But these are two different types of regimes. In minimalist democracies, the electoral process and political institutions do not systematically favour the government. In an electoral autocracy, however, this would be the case. As Hager Ali's introduction to this series argues, such a lack of precision threatens our capacity to test hypotheses, generalise findings and propose policies.

Recently, scholars have developed many concepts and measurements to locate electoral autocracies on the authoritarian–democratic spectrum of regime types. Scholars agree that electoral autocracy is today's most common form of autocracy. Yet they are divided on the relevant properties that differentiate such a 'hybrid regime' from democracies and other autocracies.

One group takes an institution-based approach, focusing on the quality of institutions supporting the government. It envisages electoral autocracies as dictatorships that hold limited contested elections, evaluated as 'free and fair elections.'

The second perspective, an actor-based approach, emphasises the ruling coalition's characteristics to classify regime types (e.g., are the military or politicians in the executive?). Here, electoral autocracy starts when party-based regimes hold multiparty elections to fill legislatures. It ends when the government is deposed through violent means or elections.

Scholars agree that electoral autocracy is today’s most common form of autocracy. But they are divided on the relevant properties that differentiate such a 'hybrid regime' from democracies and other autocracies

These two ways of understanding electoral autocracy highlight key conflicting assumptions regarding the 'rules of the game' and the role of 'players' in political dynamics.

On the one hand, the institution-based approach assumes that elections and legislatures signal the government's effective head (civilians) and constrain actors' decisions and strategies.

On the other hand, the actor-based approach considers such institutions as a complete charade. Legislatures and politicians tend to play a marginal role in the life of autocracies because they are subservient to the ruler's decisions.

Table 1 shows four famous operationalisations of electoral autocracy. Scott's index in Table 2 informs the extent to which scholars agree with identifying a regime as electoral autocracy, based on their theory approach and knowledge about a country.

| Schedler (2013) (Institutional approach) | HTW (2013) (Institutional approach) | Brownlee (2007) (Actor-based approach) | GWF (Actor-based approach) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset | Freedom House | Authoritarian Regime Dataset v.5 | Geddes et al's (2014) Autocratic Regimes v.1.2 and Keefer's (2012) Dataset in Political Institutions | Geddes et al’s (2014) Autocratic Regimes v.1.2 and NELDA |

| Time coverage | 1980–2002 | 1972–2010 | 1975–2010 | 1946–2010 |

| Small countries | No | Yes | No | No |

| Total number of countries covered in any year | 151 | 192 | 151 | 192 |

| Total number of countries with electoral autocracies covered in any year | 51 | 81 | 66 | 64 |

The results show little consensus exists on identifying electoral autocracy. Specifically, there is a 34% probability that scholars agree when coding the same countries over a similar period.

Scholars might share an understanding of how electoral autocracy differs from other regimes. However, transforming these ideas into coding criteria provides a different set of country-year observations.

For example, in the institution-based approach, the distinction between electoral autocracies and other regimes is based on experts' assessment of election quality. This evaluation, being subjective, produces a 56% probability of agreement about the limits at which an electoral autocracy starts and ends in a given year.

| Perspectives | Number observations | Coefficient (interval at 95%) |

|---|---|---|

| All datasets | 1,201 | 0.34 (0.31–0.38) |

| Institution-based perspective | 1,201 | 0.56 (0.53–0.60) |

| Actor-based perspective | 1,201 | 0.65 (0.62–0.68) |

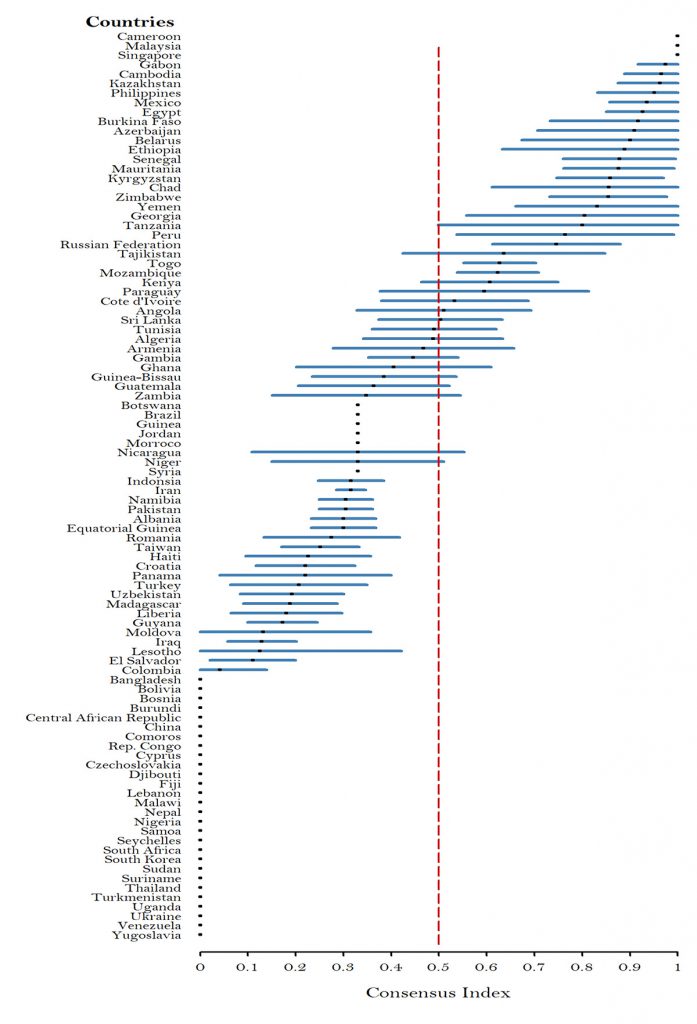

Given this lack of scholarly consensus, what countries do represent clear instances of electoral autocracies? The graphic below shows the ranking of countries (y-axis) over the 1980–2002 period based on the Consensus Index (CI) scores (x-axis). The higher a country is in the ranking, the more likely a 'hybrid regime' configuration resembles those we expect in electoral autocracies. That is, elections and legislatures are sufficiently meaningful in the constitution of power that political actors must heed. Second, multiparty elections signal that the executive and legislative power are in the hands of civilian elites. Finally, incumbents violate institutional rules for their benefit and at the opposition's expense.

The above graphic shows that 23 out of 96 countries have experienced 'clear instances' of electoral authoritarianism. These are countries where three out of four authors agree on coding the same country in any year as electoral autocracy (CI = 0.66). Cameroon, Malaysia, and Singapore are the clearest examples of these regimes. As the ranking goes further down, disagreements become more evident. For example, from 1980–2002, only one dataset identifies Venezuela and Yugoslavia as electoral autocracies.

Electoral autocracies seem to be the most common form of dictatorship precisely because the concept has been used as a blanket term. Given the lack of consensus among scholars in identifying this regime, I suggest three guidelines to avoid comparing apples and pears.

Electoral autocracies seem to be the most common form of dictatorship precisely because the concept has been used as a blanket term

First, we need to better conceptualise and measure regime types, as this series discusses. Future studies might benefit from analysing why scholars disagree on how to identify electoral autocracies. By so doing, we may develop more nuanced criteria for conceptualising and measuring regime types. If we have doubts about coding decisions, we should explain the source of uncertainty in the dataset documentation.

Second, datasets on political regimes are based on assumptions about what constitutes a regime and what dynamics are equivalent to regime change. Against this backdrop, we should select and cross-check those datasets that match our theory assumptions regarding the 'rules of the game.'

Third, studies focusing on electoral autocracies or other regimes must ensure that the sample displays the 'rules of the game' we expect in such a regime configuration. And they must discuss the sample or case selection's implications for inference and generalisations.