As population growth slows, Miroslav Nemčok and Rein Taagepera draw on a striking demographic stall 2,000 years ago that preceded political fragmentation and imperial collapse. What does it mean for today’s institutions — and can modern states withstand the pressures of a post-growth world?

Not long ago, the global population hit five billion — a milestone so momentous that it inspired the creation of World Population Day in 1987. Since then, growth hasn’t just continued — it has accelerated at a historic pace. The world is continuing to grow — and fast.

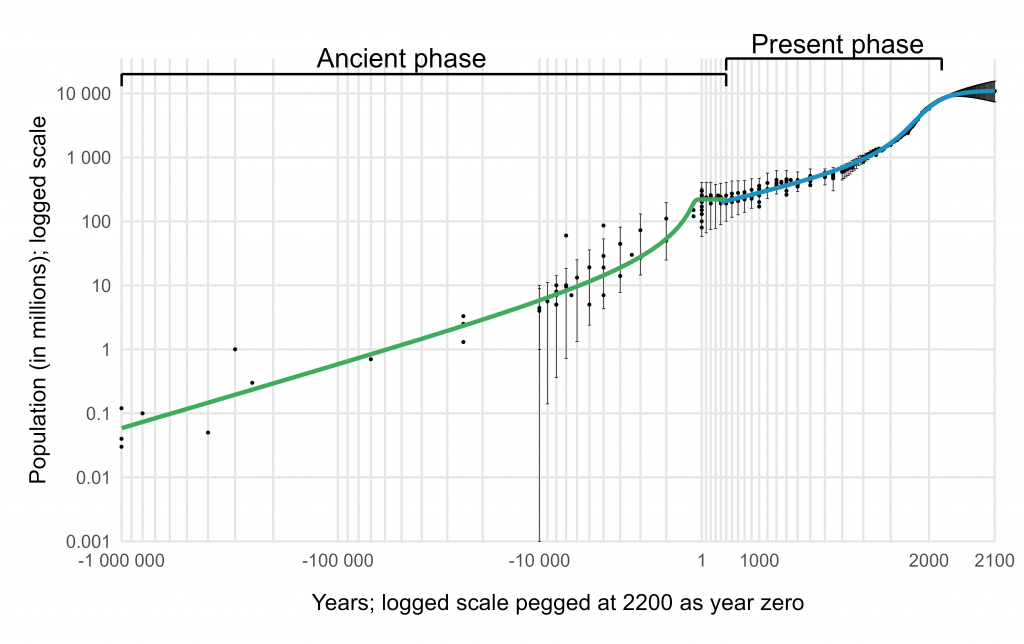

In just 37 years, the global population has surged to over 8.2 billion. That means 3.2 billion people — nearly 60% of today’s population — have been added since the United Nations Development Programme first recognised World Population Day. For comparison, the 37 years leading up to 1987 saw an increase of fewer than two billion people. And prior to that, it took a full century, from around 1830 to 1930, to add a single billion.

But this explosive growth is now decelerating. Although the global population is still increasing, the pace has peaked. The growth rate peaked around 2010 and has been declining steadily since. Most projections now suggest that the world population will level off at around 11 billion by the end of this century, after which it may begin to decline, potentially stabilising at a lower level.

The implications of slowing population growth for modern societies are profound. Despite the many challenges we face today, life for much of the global population is significantly more comfortable than it was just a few generations ago — largely because of the rapid demographic expansion over the last half-century. Modern economies and welfare states have depended on a steady supply of working-age people to drive growth, fund public programmes, and support ageing populations.

Pension systems, labour markets, and healthcare infrastructures are struggling to adapt to ageing populations, forcing a fundamental rethinking of how societies function

But many of the institutions built during this period — pension systems, labour markets, and healthcare infrastructures — are struggling to adapt to a new demographic reality. Shrinking workforces and ageing populations are increasing pressure on social safety nets. The environmental costs of past growth — most urgently, climate change — are forcing a fundamental rethinking of how societies function. The systems on which we have long depended are becoming increasingly difficult to sustain.

At the same time, disillusionment appears to be spreading. In many countries, people feel that social contracts have been frayed or broken; that the state no longer delivers on its promises. As trust erodes, so too does the willingness to contribute to collective institutions. Left unaddressed, these shifts risk not just economic instability, but the unravelling of the very structures that have underpinned modern civilisation.

It is rarely acknowledged, but the impending standstill in global population growth has a precedent in the ancient world. Between 1000 BCE and 250 BCE, the global population surged from around 42 million to 170 million, a fourfold increase in just 750 years. Then, growth abruptly halted. The world population declined by some 10%, and remained stagnant for roughly half a millennium, until around 400 CE.

This demographic plateau coincided with a wave of political fragmentation. Around 100 CE, the Han, Roman, and Kushan Empires collectively governed more than half of the world’s population. Within a few generations, all three had fractured. The Han dynasty collapsed into the chaos of the Three Kingdoms period, the Roman Empire split under mounting military and economic strain, and the Kushan Empire disintegrated amid shifting regional power dynamics. These weren’t isolated collapses; they were systemic breakdowns, shaped in part by the demographic and technological limits of their era.

As population growth slows, we may no longer have access to resources which economies of scale now render widely available

During their growth phases, these empires experienced prolonged periods of relative stability and prosperity. In our time, the past 70 years have brought extraordinary gains in health, comfort, and life expectancy. But a new phase is beginning. As population growth slows, the engines of economic expansion and technological innovation may begin to lose momentum. Resources that have become widely accessible — thanks in part to economies of scale — may no longer be as abundant or affordable.

The last major population stall, which began around 100 BCE, may have been reversed around 400 CE by a quiet yet transformative shift: the improved use of written records. Written records enabled coordination across vast space and generations, laying the groundwork for cooperation and, eventually, technological breakthroughs that raised the planet’s carrying capacity.

What breakthrough might play that role for us today? We simply don’t know. General artificial intelligence? Quantum computing? Space colonisation? Each holds promise, but history reminds us that it is notoriously difficult to predict the true impact of transformative technologies at the moment they emerge.

Human intervention, whether personal or political, is unlikely to reverse the long arc of demographic change. For over 1,600 years, population growth has followed a steady path: rapid acceleration, now giving way to gradual slowdown. Even disasters like the Black Death or world wars only briefly disrupted this trajectory.

We may be entering a phase of demographic stagnation — but in a world of ageing populations, stability may be beneficial

We may be entering a rare historical phase of prolonged demographic stagnation, much like the one between 100 BCE and 400 CE. And, as then, the influence of individuals or governments may be limited.

But this doesn’t mean resignation. Rather, it calls for a shift in expectations. The postwar decades led us to assume constant progress — but in a world of ageing populations and environmental strain, stability may become the new success.

Perhaps the most meaningful response lies in mindset. To value continuity, embrace modest hopes, and build resilience. If today isn’t worse than yesterday, that alone is worth appreciating.