Felia Allum argues that to fully understand organised crime groups, we should listen to women's voices. To recognise women's agency, we must move beyond the master narrative that sees them purely as victims, or as an irrelevance

Words are powerful tools to express feelings. But we can also use them to control and influence other people. Words are systematically used to speak over women, to silence them, and render them invisible. This happens, too, in the world of organised crime. In this scenario, however, the situation is less straightforward.

My recent research looks at women in transnational organised crime groups, or OCGs. A key point that emerged from this research was the need to give women a voice. In particular, there is an urgent need to challenge oversimplified narratives that cast all women in OCGs as victims, or merely as male representatives, without agency. Even the criminal underworld itself considers women inferior beings. And yet...

In our book, Graphic Narratives of Organised Crime, Gender and Power in Europe: Discarded Footnotes, artist Anna Mitchell and I give a voice to female actors in the criminal landscape.

I collected interviews with girls and women from a variety of criminal underworlds. I gave these to Anna to digest and interpret. What developed was a co-production and conversation about these women's lives, choices, and agency. Anna transformed the women's accounts into striking graphic vignettes, with speech bubbles, to convey these women's isolation, their decisions and their power in OCGs.

The stories, based on my ethnographic interviews, illustrate the complex lives of women who seek to survive not only as victims, but as women with the agency to make decisions.

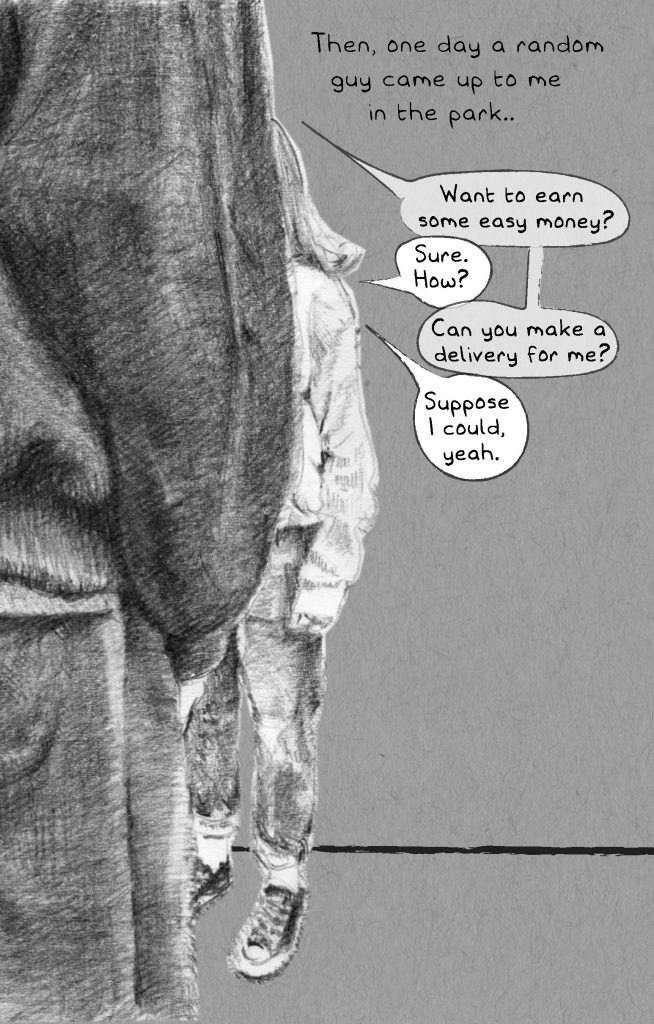

Rosie, a shy 14-year-old living in the United Kingdom, had dropped out of mainstream education. She became invisible to the authorities, and to society.

At a low ebb, Rosie got caught up in county lines drug-running. Her so-called boyfriend set her up in trap house, an abandoned flat, where he demanded she sell drugs to addicts.

Many young people in Rosie's position fall victim to gendered violence. Young boys are plugged; girls forced to perform sex acts. Luckily, Rosie managed to escape, and returned home. She survived.

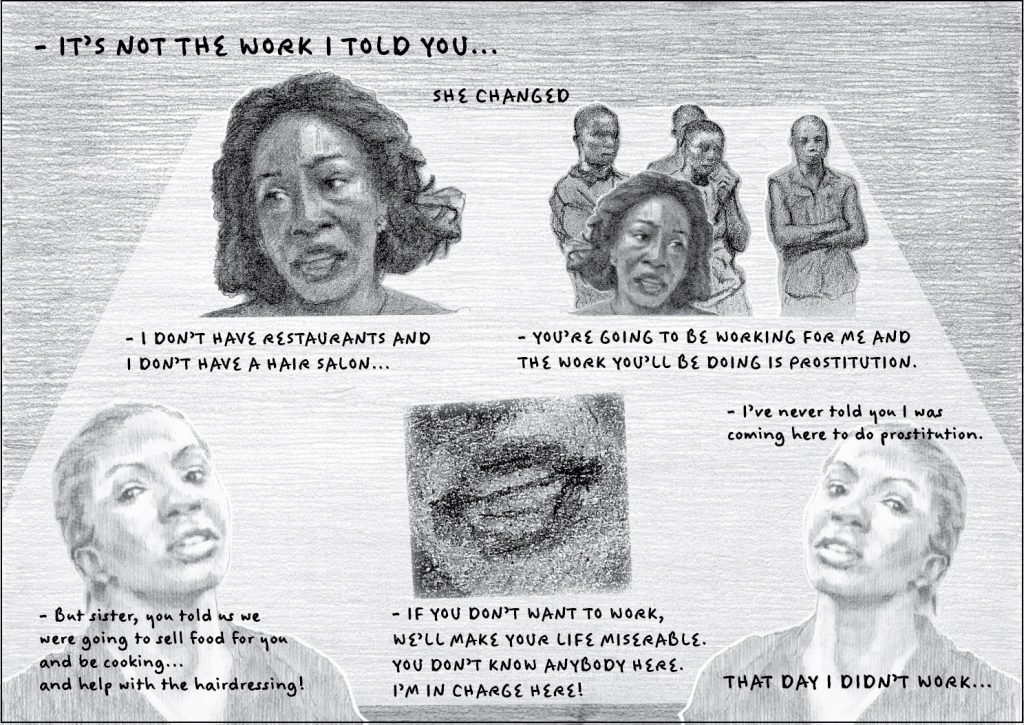

Kemi was a young Nigerian woman. Duped into thinking she was off to find a hairdressing job in a European city, Kemi set out on a long boat journey from her home country.

In fact, Kemi's father had sold her to a trafficker. Kemi ended up as a sex worker in Libya for two years, under the control of a fearsome and determined madam (pimp) with links to Nigerian brotherhoods.

Eventually, Kemi made the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean to the island of Lampedusa. From there, she had been supposed to travel on to work for another madam in the Italian municipality of Castel Volturno. But rather than contact her, Kemi instead sought help from an NGO, and found security.

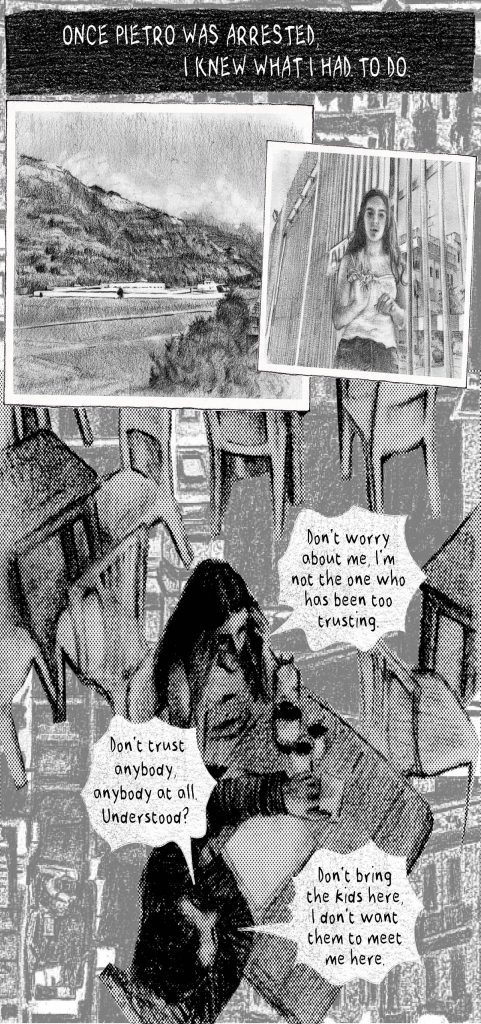

Rita was the wife of a local Camorra boss, Pietro. When Pietro was arrested, it was she who carried on managing the clan, its activities, and members, on her own.

The boss's brothers were not so keen on Rita being in charge, 'because she was a woman', but Rita managed intelligently – until, that is, she fell in love with someone outside the clan.

When her brothers-in-law found out, there was no mercy. The Camorra tried to take Rita's children away from her.

To keep her children, Rita had only one choice. She walked away from her life of crime, her husband and the clan – and collaborated with the state.

Navigating the criminal underworld is brutal, violent, and hellish. But it is especially so for girls and women. Women and girls are routinely disregarded as beings with their own agency. Society tends to see them as ‘extras’ to a criminality beyond their control. We consider such women to be ill, mad or freakishly sexual beings. At least, this is what mainstream criminology tells us.

When women get arrested, the system punishes them not just for being a criminal, but for being deviants who would rather pursue criminality than motherhood

But when women and girls get arrested, the system punishes them not just for being a criminal, but for being female. This does not happen to men. An often-unacknowledged sexist paradox exists which supposes that women in OCGs are passive because OCGs are male-dominated structures. But when women are arrested, they are also hit by another layer of sexism. Society punishes those bad, deviant women who would rather pursue criminality than motherhood.

My research reveals how it is not the criminal organisations themselves that are sexist. Rather, it is the way we analyse them and talk about them. As Professor Elaine Carey eloquently explains, women in organised crime are hidden in plain sight.

I have spoken with women who have lived and survived in criminal spaces. These interviews opened my eyes to their multi-layered existence. It is easy to ignore such nuances if we do not hear these women's voices first-hand.

It is easy to ignore the multi-layered, nuanced lives of women in organised crime if we cannot hear their voices first-hand

Paradoxically, I ended up arguing against the narrative which considers women purely as victims of patriarchy. I could see that many women in the criminal underworld made their own decisions – good or bad – under the aegis of patriarchy. However, their decisions were, at least, their own. These women had free will. To use Deniz Kandiyoti’s expression, they negotiated and ‘bargain[ed] with patriarchy’.

Western societies are based on male values and a preferential system that oppresses women. Yet while I acknowledge this oppression, and while a cultural and sexist hegemony prevails, I still believe women have the agency to bargain with this patriarchy in their own way.

The fuzzy puzzle that is organised crime is made up of many contradictions. I believe it is important to shed light on such contradictions. The women's stories featured in our graphic narrative transcend slick movie stereotypes, and academic rhetoric. We gave a voice to women society considers 'powerless' – but who in fact have an agency they use on a daily basis to survive and thrive amid criminal underworlds. Using pictures for words, we empowered the women mainstream society continues to either dismiss as irrelevant, or to ignore.