You might think that most people have misperceptions about immigration. Yet many false beliefs are merely low-confidence guesses, rather than firmly held views. Drawing on new Swiss survey evidence, Philipp Lutz and Marco Bitschnau show that this distinction has important implications for understanding public opinion, and for the quality of democratic debate

Public debate is quick to conclude that many people harbour entrenched false beliefs about immigration. From inflated estimates of immigrant numbers to exaggerated ideas about crime or welfare use, we tend to treat misperceptions as common and consequential. This is not entirely unfounded. But our latest research, published in Political Science Research and Methods, suggests a different and considerably more mundane explanation: many of these supposed misperceptions are, first and foremost, just the product of bad guessing.

This distinction matters. A confidently held false belief has a very different political life from a tentative, low-confidence estimate given by someone who has never thought much about the issue. But most survey approaches to measure perceptions fail to make this distinction. They tend to treat both response categories as identical, with severe consequences. For when we do not distinguish misperceptions from uninformed-ness, we risk overstating the scale of the problem while also misunderstanding its causes and consequences.

And there is a second, more issue-specific problem. Scholars have long relied on a single question to gauge perceptions of immigration: asking respondents to estimate the immigrant share of the local or national population. This, of course, is a sensible starting point, because the number is easy to communicate and politically salient. Yet it has also come to function as a conceptual crutch, given that immigration is a multidimensional phenomenon, while the measurement of perceptions remains strikingly narrow. It conflates genuine misperceptions with general innumeracy (the difficulty of interpreting numerical information), which may distort our understanding of what the public actually believes.

To address both problems, we developed a new module, administered in a Swiss population survey, that broadens not only which questions we ask but also how we capture perceptions.

First, we move beyond the standard item on the population share of immigrants by including six perception questions across three different dimensions: culture, economy, and security. All three capture issues that surface routinely in public debate, from the immigrant unemployment rate to the share of immigrants holding university degrees. In this way, we gain a more comprehensive picture of how citizens form their views on immigration.

Our survey module separates actual false beliefs from uninformed guesses, helping to close the gap between the conceptualisation of misperceptions and their empirical measurement

Second, we paired each perception item with a confidence scale. After giving their estimate, we asked respondents a follow-up: How confident are you that this estimate is correct?

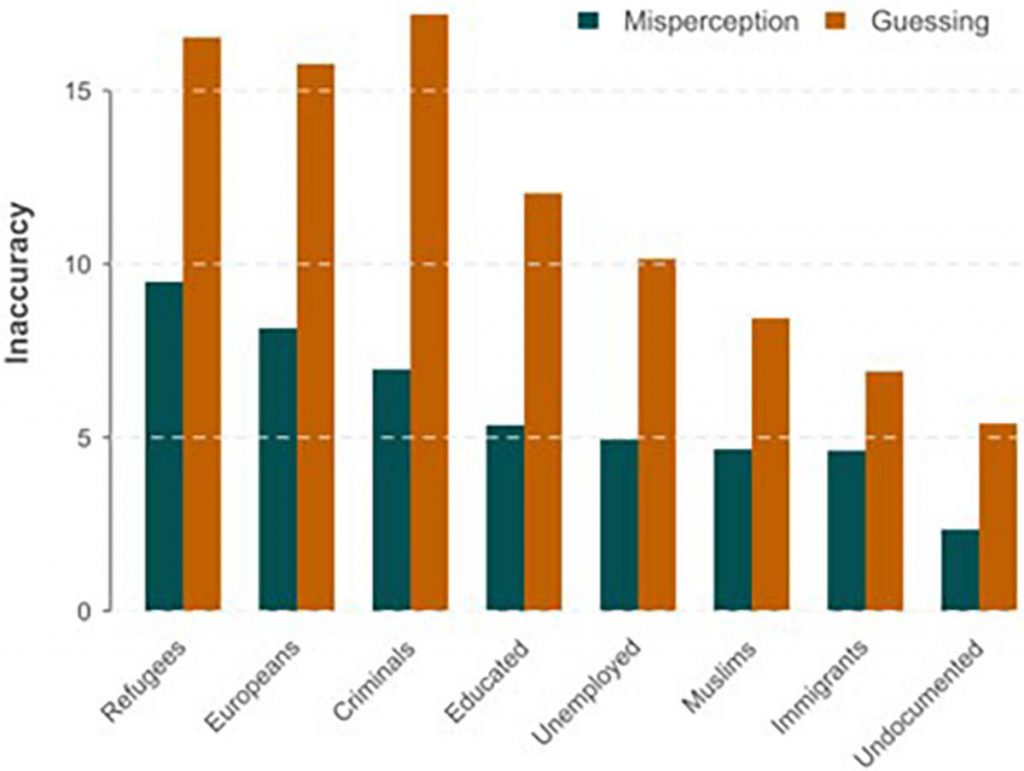

This allows us to construct two distinct measures; namely, genuine misperceptions (inaccurate answers given with high confidence) and bad guesses (inaccurate answers given with low confidence). In other words, we can separate actual false beliefs from uninformed guesses and thereby help close the gap between the conceptualisation of misperceptions and their empirical measurement.

Across all items, respondents offer estimates that vary widely, at times overshooting and at times underestimating the official figures. At first glance, this variation appears to confirm the familiar story of widespread misperceptions. Yet once we factor in confidence, a different pattern emerges. For most items, a substantial number of respondents expresses little to no confidence in their answers. Indeed, confidence levels are generally low, so that inaccurate responses fall predominantly into the area of guesses rather than genuine misperceptions.

Crucially, misperceptions and guesses are also structured differently at the attitudinal level: people with more negative views of immigration tend to exhibit higher misperception scores, consistent with established theories of motivated reasoning. Guessing, by contrast, shows no such pattern. It is essentially random error. This underscores that only misperceptions — not guesses — bear the imprint of political predispositions.

Our survey revealed that only citizens' misperceptions about immigration — but not ther guesses — bear the imprint of political predispositions

Even when surveys register a wildly inaccurate estimate, this need not signal an ideological stance. More often, it reflects limited knowledge, indifference to such knowledge, or simply a respondent’s difficulty in handling numerical information. Such inaccuracies frequently stem from the improvised nature of on-the-spot-responding. People provide their best estimate simply because the survey demands a reply.

This changes how we should interpret the magnitude and character of misperceptions about immigration. To begin with, the problem may be mischaracterised. If only a small minority of inaccurate responses arise from high-confidence beliefs, then the popular claim that people are deeply and chronically misinformed warrants some reconsideration. In many instances, respondents are not rejecting empirical reality but navigating it with only a partial sense of the relevant figures.

That said, knowledge may likewise be overstated: some people gave correct answers with low confidence, too. This suggests that accuracy may equally result from lucky guessing rather than informed beliefs. The well-informed citizen (once central to democratic theory) appears as elusive as ever these days, and such blurring of accuracy and uncertainty only complicates how we infer competence from survey responses.

Providing citizens with straightforward information may be more effective than commonly thought, especially when targeted at the unsure

This distinction carries significant implications for policy and political communication. Were all false answers misperceptions, any attempt to correct them would have to contend with motivated reasoning and identity-driven beliefs. But if many arise from uncertainty instead, straightforward information provision may be more effective than commonly thought, especially when targeted at the unsure rather than the already certain.

In the end, our evidence points to the conclusion that many errors commonly attributed to misinformation and ideology rest on shaky foundations. Rather than representing entrenched worldviews, many of these inaccuracies turn out to be houses of sand: they collapse once we take into account how limited respondents’ confidence often is. If we fail to separate beliefs from guesses, we risk battling ghosts and misconstruing uncertainty or confusion as political commitment.