The new wave of strong executives in Latin America is not only the result of their forceful attempts to push their legislative agenda, or of their popularity. In Mexico, for example, there are institutional disincentives to empower Congress. The result, argues Carlos Vázquez-Ferrel, is a weak and disillusioned legislative opposition

At the beginning of 2023, Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, succeeded in approving significant reform of the Instituto Nacional Electoral (INE), Mexico's autonomous agency for organising elections. The General Congress of the United Mexican States approved this reform without serious challenge. Similarly, in April, the Mexican Congress approved more than 20 laws promoted by the President in less than 25 minutes. Both reform processes showed that the legislative opposition was distracted, uncoordinated, or even absent – all of which facilitated the bills' approval.

Mexico's Congress is the site of a distracted, uncoordinated, or even absent legislative opposition, allowing the President to push his own agenda

The governmental legislative coalition is losing cohesiveness as the competition for presidential succession intensifies. But the Mexican opposition is not using this opportunity to oppose President Obrador’s new agendas.

The new wave of strong executives in Latin America does not stem only from their attempts to push their legislative agenda reforms, or from their popularity. My forthcoming study examines the Mexican Congress with references to other Latin American cases. It shows that the weak foundations of this institution disincentivise the creation of strategies to strengthen checks and balances.

In democratic systems, Congress has a crucial role in controlling the executive. But in Mexico, the reality is that Congress is far from filling this essential role. The system of checks and balances is weak. Over time, it may weaken yet further as a result of economic or security crises. The executive could exploit these crises to legitimise its consolidation of power.

The debilitation of Mexico's Congress coincides with the first time in 90 years that legislators have been able to seek re-election. Previously, the Constitution had prohibited re-election. Lifting this prohibition was intended to strengthen the relationship between representatives and voters. It assumed that ratification would be a means of rewarding good politicians.

In 2021, 201 of the 500 Mexican Congress Chamber of Deputies representatives decided to run for re-election. Based on analysis of the US Congress, some scholars have assumed that when legislators choose to remain in Congress, it is because it offers political benefits. This desire would lead to the consolidation of Congress.

But conditions in Mexico differ from those in the US. In Mexico, as in Uruguay and Chile, party leaders influence policy by promoting bills, amendments, or other instruments. Legislators seeking re-election require 'reselection' by the same party or coalition that originally nominated them, unless they have resigned their candidacy before the middle of their term and received the endorsement of another party. This means that parties and their leaders retain strong control over individual legislators.

Congress offers legislators limited resources, little opportunity to influence policy, and uncertain electoral advantages

Many legislators in Latin America lack the adequate budget and staff. This prevents them from connecting solidly with their constituents, and weakens their capacity to control the Executive. Also, as in other federal countries, local-level executive positions in Mexico are more attractive than Congressional ones, especially in bigger cities. Such posts offer access to larger budgets in a system with weak accountability, which could boost politicians' careers.

The paradox, then, is that so many Mexican legislators seek re-election. Congress offers them little opportunity to influence policy, limited resources, and uncertain electoral advantages. Meanwhile, they could be contending for other valuable positions more likely to advance their political careers.

Committee chairman is a position designed by the party leadership. Chairmen can accelerate or block any legislative decision within the committee. My forthcoming research demonstrates that of the 44 committee chairmen in the LXIV Legislature of the Mexican Congress, around 56% were reselected to compete for re-election.

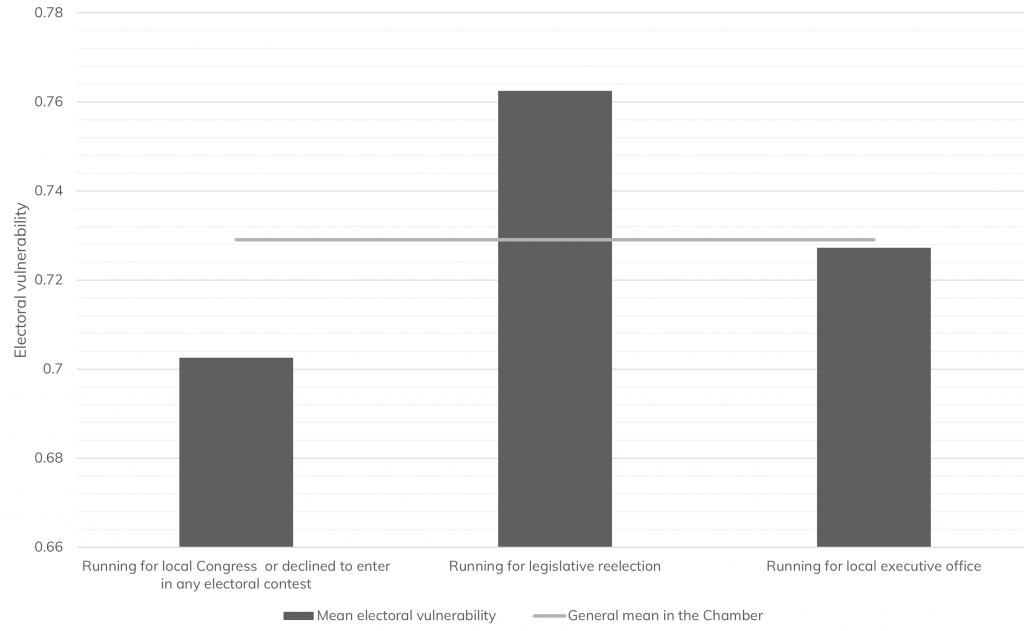

Most of the legislators who were renominated by the party leadership to run for re-election had performed poorly in their previous contests. More poorly, in fact, than those parliamentarians who chose to run for a local Congress, compete for executive local office, or decline any electoral competition.

Party leaders defended the political survival of their closest legislators by reselecting them to run for legislative re-election. This is a less political desirable position to run for. However, it avoids the risk of facing eventual electoral defeat for a more competitive position, as would be an executive post at the local level.

Legislative re-election is the safest bet to survive in Mexican politics, and party leadership uses it to preserve their closest legislators

The motivations behind the decision to seek re-election in Congress do not lie in the incentives that this institution itself offers. Nor are they born from a personal desire to build a legislative career. Rather, the motivation lies in the perceived risk of being outside Congress. Re-election is the safest bet to survive in politics, especially for legislators whose previous electoral performance is poor, but who are close to the party leadership.

So what happens if today's electorally vulnerable legislators become well-known politicians? Perhaps they will refuse to run for re-election in a Congress where decision-making sits within a small circle of politicians. Instead, they may prefer to seek a position in the executive branch, where they can access and distribute more resources.

As a result, it is highly improbable that they will lead the professionalisation and empowerment of the legislative branch. The Mexican Congress, under these circumstances, will continue to perform a less challenging role in the policymaking process. Therefore, the President's agenda and attempts to enhance power will continue to dominate.