Scholars and the media often portray the ongoing polycrisis as undermining the EU’s self-understanding. This has led observers to describe the EU as an ‘anxious community’. But Franziskus von Lucke and Thomas Diez find that, on the contrary, EU actors remain surprisingly confident. While this may look like a positive finding, the authors argue that the EU needs more, not less, anxiety to deal successfully with current and future challenges

Euro crisis, Brexit, migration, Covid, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, war in the Middle East... an ever-increasing list of crises confronts the EU. But to what extent do these pose a fundamental challenge to the EU’s ‘ontological security’?

In contrast with physical security, the term ‘ontological security’ refers to positive, stable constructions of an actor’s self that help them cope with change and challenges. In the wake of the above-mentioned crises, political practitioners, the media, and scholars alike are seeing increased ontological insecurity. This has led them to call the EU an ‘anxious’ or ‘insecure’ community. However, if we take a closer look at the development of debates in the European Parliament (EP) across different policy fields and over a longer period of time, the picture becomes more nuanced.

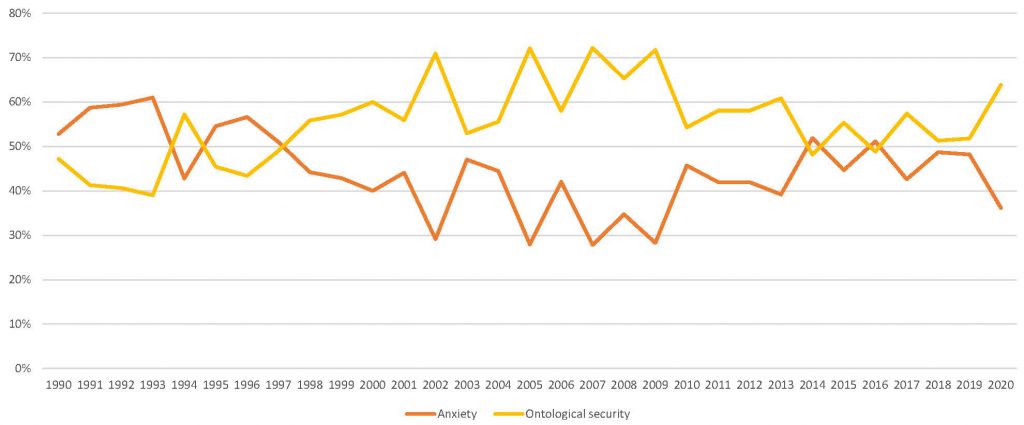

In key plenary debates between 1990 and 2020, Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) show a surprising degree of confidence. As the line graph below shows, this reaffirms their ontological security more than articulating a deep-seated anxiety. MEPs rarely become desperate or portray the EU as intrinsically inequipped to cope with the challenges they face. Instead, they tend to construct the Union as a ‘crisis professional’ which has developed a capacity to deal effectively with almost any challenge.

Members of the European Parliament tend to construct the Union as a ‘crisis professional’ with capacity to deal with almost any challenge

Indeed, we found the highest levels of anxiety in MEP speeches not in the 2010s but in the 1990s, when EU institutions – especially Parliament – lacked established routines that could have strengthened a sense of ontological security. A prolonged dominance of articulations of ontological security followed throughout the 2000s. While anxiety returned in the 2010s, it never became as widespread as in the EU’s early years.

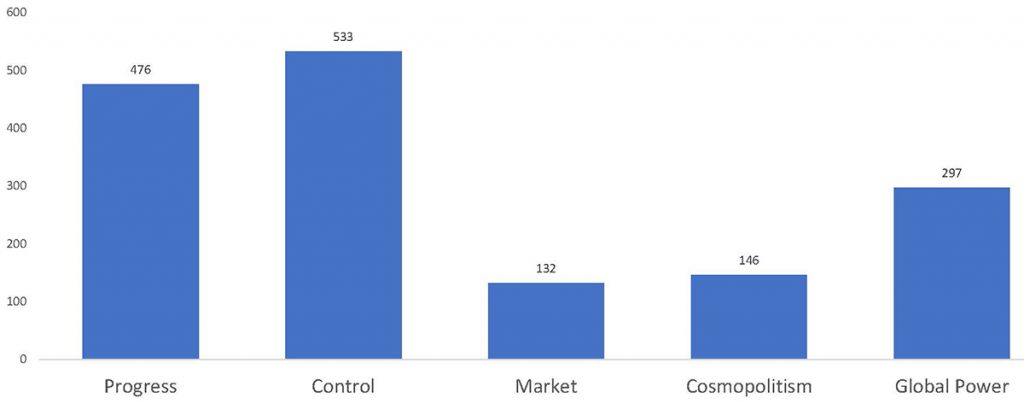

To reaffirm the EU’s ontological security, MEPs refer to a range of broad narratives or storylines that help make sense of the world and construct the EU's particular role in it. As the graph below shows, they see the EU mainly as the torchbearer of historical progress, as being in control, and as a global power.

The narrative of progress includes a very particular understanding of history as moving forward in a linear and self-evident manner without viable alternatives. In this picture, Europe has overcome its violent past and moved towards a world of prosperity, rule of law, and safeguarding the global climate. On the flip side, this narrative delegitimises extensive self-reflection. Hence, it leaves critical interrogations of the further development of the Union to political fringe groups such as Eurosceptic and populist parties.

An overly rigid and unquestioned understanding of Europe as having overcome its violent past and providing prosperity and the rule of law discourages constructive speculation about alternative directions of development

This vision of progress is closely linked to the idea that the EU is able to control natural, social, and political processes, to accurately map problems and to plan and verify counter-measures. One key example is the EU’s attempts to control the climate through a range of technological and economic measures. Another is its efforts to regulate migration flows through surveillance or increasingly strict border regimes. This vision of control displays a deep trust in legal and technocratic expertise. It reinforces a modernist bureaucratic discourse with an emphasis on expert governance.

Finally, MEPs also increasingly construct the EU’s ontological security as linked to the notion of the EU as an important global power that contributes to making the world a better place. And while they often concede that the EU is not yet such a power, the fact that it ought to play a more important role on the world stage – something the international community and EU citizens supposedly want – is hardly ever disputed.

Unquestionably, too much insecurity is a problem for actors. A fundamentally insecure EU would not be able to cope with the polycrisis, protect its citizens, or further solidarise international society. At the same time, an unquestioned and excessive degree of confidence is also problematic. It leads to what others have called a ‘rigid’ or ‘maladaptive’ sense of ontological security. This includes a self-centred and fixed identity that fails to listen to others or to recognise difference, and which tries to impose its own views onto others in a Eurocentric, missionary manner.

A certain degree of anxiety is necessary for the EU to foster a ‘healthy’ sense of ontological security

Thus, a certain degree of anxiety is necessary for the EU to foster a ‘healthy’ sense of ontological security and a ‘critical distance’ to itself. It would enable the EU to constantly check its tendencies for narcissism and increase its ability to cooperate with others towards achieving progressive change and adapting to new challenges. It would also help the EU to leave room for doubt and introspection and not surrender productive criticism of the integration process to political fringe parties.

A positively anxious EU would be able to problematise its currently largely unquestioned modernist and technocratic underpinnings. To minimise the risk of negative unintended consequences, it would need a more critical stance towards technological possibilities of progress and control, without rejecting technological innovation altogether.