Many extremist organisations exist and operate in democratic societies. Some get banned by democratic authorities; others don’t. Why? Using data on far-right organisations from Germany, Michael Zeller explains why governments ban only some of the organisations working to undermine Germany’s constitutional democracy

Across European democratic societies, there exist many extremist organisations which act unlawfully, and are antagonistic to constitutional democracy. To rein in such organised extremism, states are, increasingly, resorting to bans. But which organisations get banned, and why?

As the archetype of militant democracy, where political rights can be selectively restricted to protect liberal democratic order, Germany has used powers to ban extremist organisations relatively frequently. Not every extremist group, however, ends up on the receiving end of a ban. Germany therefore makes a particularly good case study of why a democratic government has decided to ban far-right organisations over the last three decades — and what these decisions reveal about democracy's limits.

Germany’s Interior Minister (in the case of organisations) and its Federal Constitutional Court (in the case of political parties) can ban organisations that threaten Germany’s democratic order and constitutionally enshrined values.

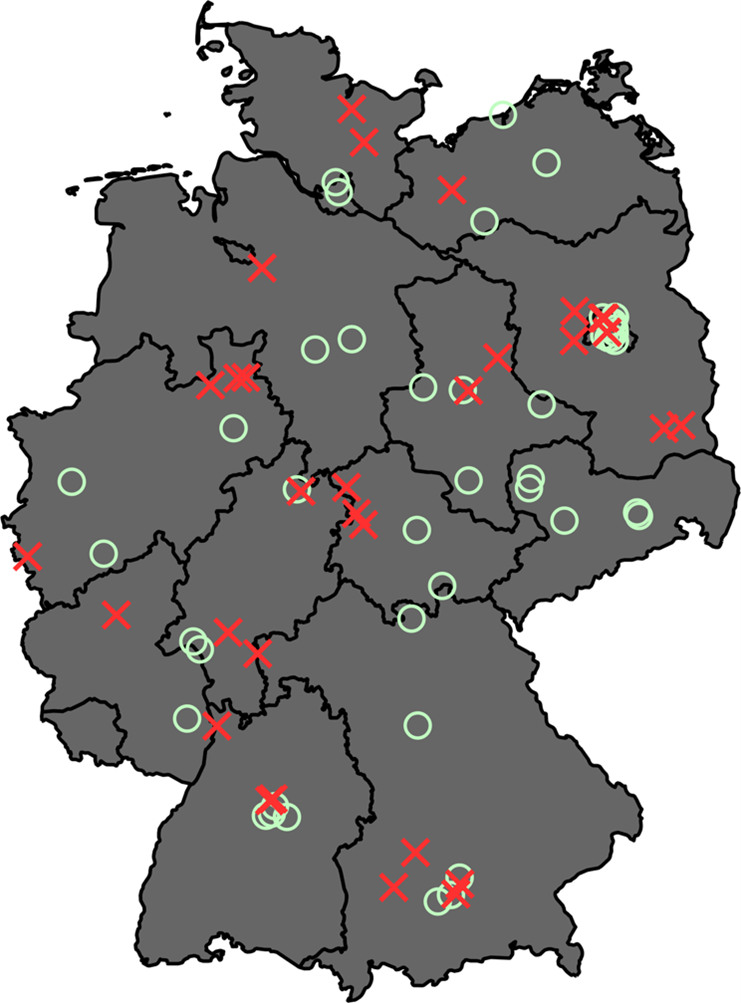

Map showing the dozens of far-right organisations monitored by Germany’s federal law enforcement between 1990 and 2023.

During that time, German governments banned 31 far-right organisations.

The green circles represent the (main) site of organisations not banned. The red crosses represent organisations banned under the Law of Associations or Criminal Code 129/129a.

My research finds that German governments banned far-right groups only in years when far-right activity, in the form of violence or agitation, was highly visible. Conspicuous incidents of violence in particular were often a prod to proscriptive action. Organisational unlawfulness alone is not enough to explain banning decisions. Without public or political awareness, authorities appear unlikely to act, even if a group is technically illegal. Public outcry, media coverage, and political pressure often play a decisive role.

Without public awareness, authorities appear unlikely to enact a ban, even if a group is illegal. Public outcry increases political pressure

This suggests that German governments’ responses to extremism are more pragmatic than principled. Banning is not just a matter of legal thresholds — it is also about timing, attention, and external pressure. In other words, bans happen not just because a group is dangerous, but because the danger becomes visible and urgent.

When the far right is highly visible, German governments repeatedly look to these types of organisations to take banning action.

My research findings challenge the idea that banning extremist organisations is simply a legal matter. Many far-right groups that meet the legal criteria are never banned. Some bans follow public incidents in which the targeted group was not directly involved.

Bans are often political tools for governments to demonstrate their responsiveness to public fear or outrage

This highlights a key point: bans are often political tools. They help governments show responsiveness to public fear or outrage. They can also help neutralise growing extremist movements by disrupting their organising and activism. Moreover, as a government once explained, banning can have a desirable chilling effect: other far-right groups 'have at least restricted their agitation activities in order to avoid bans'. But bans can also be symbolic, signalling action without changing much on the ground, within the organisational ecologies of far-right activity.

The pragmatism underlying banning decisions entails benefits and risks. On the one hand, it allows democracies to act swiftly when threats escalate. It also shows that public pressure matters — citizens and activists, media, and other parties can influence state decisions. On the other hand, it creates inconsistency. Two similar groups may be treated very differently depending on timing, media attention, or political mood.

That inconsistency raises concerns about fairness and effectiveness. Arbitrary enforcement risks undermining trust in democratic institutions. It can also leave dangerous groups untouched if they manage to stay under the radar.

Banning one group does discourage others, but the effect depends on how well the state understands the broader ecosystem of extremist activity

Still, the research also suggests that bans can be effective in disrupting extremist networks. In the case studies examined, banning one group plausibly discouraged others or limited their ability to operate. Yet this effect depends on how well the state understands the broader ecosystem of extremist activity — and whether it sees bans as a strategy, not just a legal endpoint or political tool.

Germany's history, its prominent far-right movement scene, and its governments’ longstanding banning practices, make the country a special case. But its example nevertheless holds lessons for other democracies. Many countries have used or adopted militant democracy tools, including laws for banning extremist organisations. Yet across contexts, the same basic challenge remains: laws exist, but enforcement varies.

My research points to a common pattern: bans do not just follow the law — they follow pressure. Public visibility, political will, and social mobilisation all shape outcomes. This means that organisational bans and perhaps other militant democracy decisions are not solely in the hands of governments. Societal actors inform and influence how states and governments respond to extremism.