Lesley-Ann Daniels and Marc Sanjaume-Calvet explore a paradox at the heart of Ukraine’s path to EU membership: the strongest pro-European voices are often the least supportive of minority rights. Drawing on new survey data, they call for a more adaptive and politically sensitive enlargement strategy

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine has undergone a profound geopolitical and societal shift. Public support for EU accession now exceeds 90%, according to the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. The war has anchored Ukraine’s European orientation, accelerated reforms, and created a rare convergence between elite ambition and mass approval for EU membership. And, as Maryna Rabinovych argues in her contribution to this series, Ukraine’s wartime pro-European shift is also an opportunity for the EU.

This deepening alignment is often interpreted as a triumph for the EU’s model of democratic conditionality; proof that the enlargement process continues to inspire reform and societal transformation. But beneath this apparent convergence lies a more complex and uncomfortable reality.

One of the EU’s core accession principles is the protection of minority rights. Yet in Ukraine, this norm carries heavy wartime baggage. Russia’s justification for its invasion partly relied on the claim to protect Russian-speaking minorities. In that context, Ukrainians have come to perceive minority rights less as democratic virtues and more as potential security risks.

This tension, between the EU’s normative expectations on minority rights and Ukraine’s security-driven political context, poses a challenge for the enlargement process. What happens when support for the EU does not translate into support for the values it upholds?

What happens when support for the EU does not translate into support for the values it upholds?

To investigate this, in August 2023, we conducted a nationally representative survey of 2,100 Ukrainians. We wanted to know how support for EU membership relates to attitudes toward decentralisation and the protection of minority rights; two pillars of EU conditionality.

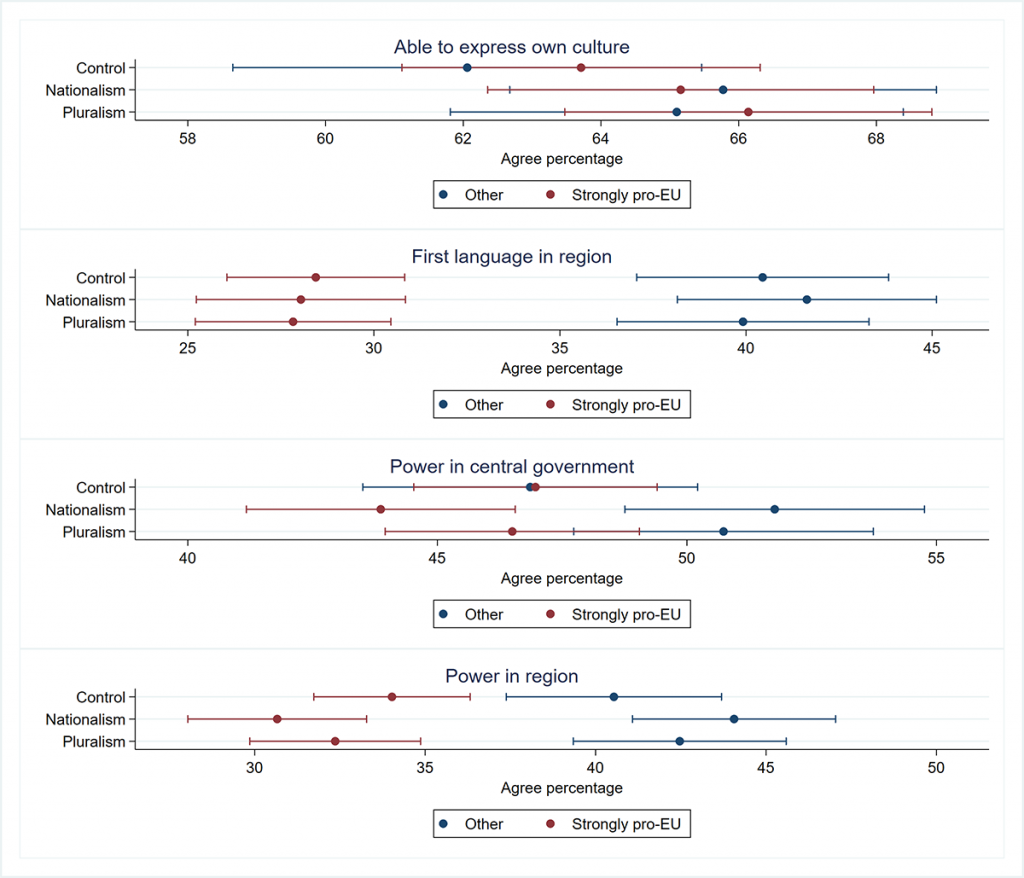

Across a series of questions, ranging from the use of minority languages in public life to the delegation of authority to regions, strongly pro-EU respondents were consistently less supportive than others. Only 28% of this group supported minority languages being used as a first language in a region where a majority spoke that language. Just 32% backed giving such regions political control over cultural or linguistic matters.

In both cases, our striking finding was that support among less strongly pro-EU respondents was significantly higher. Furthermore, it was our questions around giving rights and powers to these regions that triggered the strongest reactions. Respondents were less troubled by rights that applied to the whole country.

We ran an experiment that used maps to nudge respondents to think about Ukraine in a certain way. In one, we showed national unity, while the other emphasised democratic pluralism. Yet, as the figure above shows, these two different narrative framings had no measurable impact. Even civic nationalists, those who support a unified, inclusive Ukraine, showed little willingness to endorse reforms that, to them, signal internal fragmentation or external vulnerability.

Our findings challenge the Europeanisation assumption on the alignment between EU support and liberal democratic values. Paradoxically, in the Ukrainian case, pro-European identification exists alongside resistance to minority concessions. This suggests that people embrace the idea of EU integration for its geopolitical protection rather than its normative agenda. This instrumental support of Europe decouples sovereignty and diversity, privileging the former in wartime. Rather than deepening pluralism, Europeanisation may be reinforcing majoritarian unity.

These findings present a dilemma. As Veronica Anghel noted in this series' foundational blog post, enlargement is now a strategic necessity for the EU (see also Milada Vachudova’s contribution on the EU’s geopolitical moment). But strategy must not outpace reality. Conditionality can only succeed when reforms resonate domestically. Imposing rigid timelines or treating pluralism as a box-checking exercise risks undermining the very legitimacy the EU seeks to cultivate. As Ivan Nagornyak and Mariia Shalamberidze suggest, conditionality should probably be both trust-based and tailored.

Imposing rigid timelines for reform, or treating pluralism as a box-checking exercise, risks undermining the legitimacy the EU seeks to cultivate

In light of our findings, it would make sense, rather than diluting its standards, that the EU recalibrate how and when it advances them. As Antoaneta L. Dimitrova points out, there are several dilemmas at stake in terms of policy changes. That means sequencing reforms to prioritise areas of stronger public alignment, such as anti-corruption, rule of law, and institutional integrity. It also means investing over time in civic education, media pluralism, and public dialogue that embed minority rights in a broader project of democratic resilience.

A successful enlargement policy cannot rely solely on institutional metrics or elite commitments. It must grapple with how democratic norms are received, resisted, or reinterpreted by the societies expected to uphold them. Ukraine’s pro-European majority is real and powerful, but we cannot assume to know its democratic content. See, for example, Dmytro Panchuk on the volatility of Ukrainian public opinion on this issue.

A successful enlargement policy must grapple with how democratic norms are received, resisted, or reinterpreted by the societies expected to uphold them

Brussels must prepare for bottom-up resistance to parts of the acquis. It must develop flexible, context-sensitive approaches that do not compromise on principles but recognise the political conditions in which those principles must be implemented. Conditionality must remain a tool of transformation, not just a test of compliance.

Ukraine is not a typical candidate country. Its trajectory toward Europe is being shaped in the crucible of war. That makes democratic pluralism harder, but also more urgent. If the EU wants its enlargement policy to be both principled and effective, it must recognise when its values need defending – not only against backsliding elites, but also in the public imagination.

Europe cannot afford to mistake geopolitical alignment for democratic consensus. As Ukraine moves closer to accession, the EU must proceed with clarity and care.